Two of the world’s most sophisticated warships collided with merchant ships this year in preventable incidents that killed 17 American sailors. While those inside and out of the Navy are demanding answers to what caused the failures, the root causes are many and the fixes are far from easy.

On June 17, USS Fitzgerald (DDG-62) collided with a merchant ship 50 miles off the coast of Japan, ripping the destroyer’s welded steel hull open under the waterline and crushing the superstructure of the warship. Seven sailors drowned in the space where they slept, unable to escape after water began pouring in with no warning, according to a Navy investigation released in August.

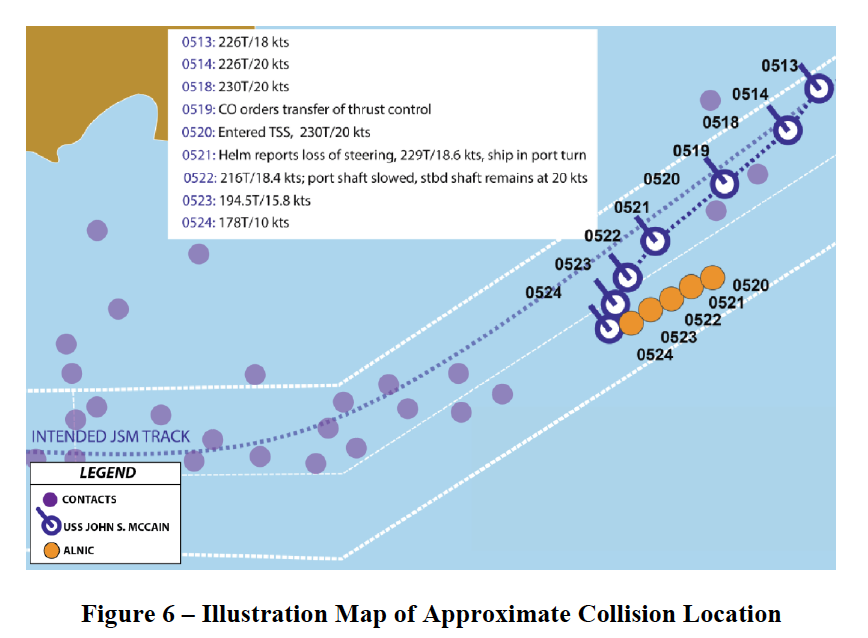

On Aug. 21, off the coast of Singapore, USS John S. McCain (DDG-56) suffered a steering casualty and crashed into a chemical tanker, which punched a hole in the destroyer’s port quarter. Ten more sailors drowned in their berthing, also with no warning, according to a Wednesday investigation report.

Combined, the McCain and Fitzgerald incidents arguably represent the worst lapses in seamanship in the U.S. surface navy’s recent history.

Findings from Wednesday’s investigation report point to split-second errors by the crews aboard both ships. In the aftermath, the Navy has admitted their surface sailors forward-deployed in the Pacific are overworked, tired and lack certifications required to perform the 22 missions required of each surface ship.

The Navy has told Congress, the Government Accountability Office and the public that it let standards lapse in its forward-stationed forces in the face of a grueling operational tempo in last several years. Document reviews and interviews conducted by USNI News reveal the surface navy has struggled with readiness, manning and training shortfalls for more than a decade.

Those shortfalls were paired with a can-do, don’t-say-no culture that tolerates surface ships deploying in less-than-optimal readiness and a relentless demand for forces from combatant commanders that has increased since China and Russia have asserted their presence in the maritime domains.

Ahead of this week’s public release of a comprehensive review of the underpinnings of the collisions, conducted by U.S. Fleet Forces Commander Adm. Phil Davidson, USNI News spoke with former surface warfare officers and Navy and Pentagon leaders to understand what led to the conditions that made the incidents on Fitzgerald and McCain possible.

High Demand

For the better part of the last decade, the Navy’s surface forces – guided-missile cruisers and destroyers and amphibious ships – have seen an increase in operational tempo in the Western Pacific as China and Russia operated more at sea.

In 2010, the People’s Liberation Army Navy began operating at a greater pace and further afield than in any time in their recent history, which prompted the U.S. Navy to pour more assets into the Western Pacific, Bryan Clark, a naval analyst at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments and former aide to retired former Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Jonathan Greenert, told USNI News.

“It’s mostly because you’re dealing with North Korea, China, South China Sea – all these new demands are increasing the emphasis on naval forces out there,” he said.

“In 2010, that’s when China started to flex its muscles in the maritime. 2011 is when they started this island-building campaign.”

As part of the U.S. response, the Navy’s Forward-Deployed Naval Force (FDNF) in Japan was tasked more for presence operations and ballistic missile defense missions with an eye toward North Korea, Clark said.

Today, the FDNF surface force is built around the Ronald Reagan Carrier Strike Group and made up of 11 ships, including guided-missile destroyers and cruisers and amphibious forces.

McCain and Fitzgerald were assigned to Destroyer Squadron 15, and they were tasked to escort USS Ronald Reagan (CVN-76) and operate as regional ballistic missile defense platforms.

The FDNF ships are permanent fixtures assigned to U.S. Pacific Command and can be deployed at short notice to deal with any flare-ups.

“It’s a much more direct line that normally would be the case,” Clark said.

“Normally if PACOM wanted something to come from outside the theater, they would have to put in a request for forces.”

As China continued a break-neck naval expansion and pushed forces further afield, the U.S. continued to increase patrols. Maintenance and training for these FDNF surface combatants were deferred, eroding the surface navy’s readiness.

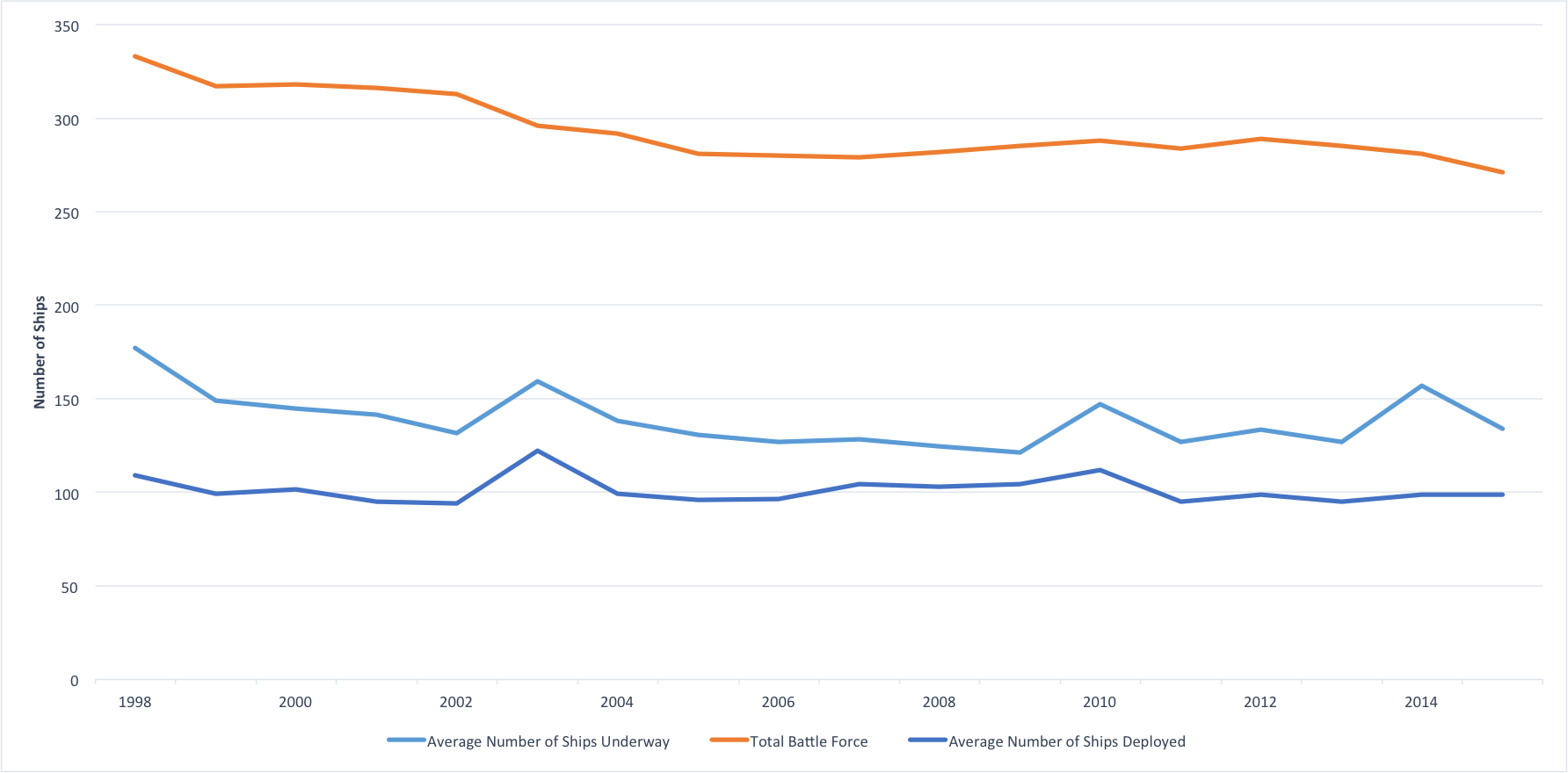

Clark studied the demands for the surface fleet in 2015, in the face of its expanded challenges, and found a higher percentage of ships were underway compared to years before without a significant increase in the battle force.

In 1999, 333 ships in the battle force supported an underway force of about a 100 ships throughout the world. In 2017 to date, the Navy had 55 fewer ships in the battle force to support the same 100-ship underway average.

The pressure that’s felt system-wide in the surface force is exacerbated for the FDNF ships due to the unpredictability of deployments.

Rob McFall served as the operations officer for Fitzgerald for 18 months, starting in 2013, and described to USNI News a grueling deployment schedule.

“When you get underway from Norfolk or San Diego, you just get to be underway. You get to train,” McFall said.

“When you get underway from Japan, you’re in the South China Sea. Whether it’s North Korea or China, it’s more stressful and it’s more real. There’s no pretending you’re going to find a submarine when you’re training; you’re actually tracking Chinese submarines.”

That experience made the sailors on the destroyers experienced in the real-world warfighting skills needed to operate, McFall said.

“An FDNF ship gets more underway time. With more underway time it gets more experience and becomes more capable – usually,” McFall said.

To be determined fully operational, a surface ship has to be certified in 22 different areas: 10 warfare areas like anti-submarine warfare and ballistic missile defense, and 12 more basic function areas like communications and, importantly, mobility and seamanship.

When McFall was serving on Fitzgerald, for example, the destroyer was U.S. 7th Fleet’s go-to ship to chase Chinese submarines operating in the region.

“Fitzgerald wasn’t certified in undersea warfare for three years because we could never find the time to get the [final certification] completed, but we were the go-to [undersea warfare] ship for any real-world tasking because we had the real-world experience,” McFall said.

However, the experience of an FDNF ship is inconsistent, and while a ship may be very good at a high-end warfare area – like finding submarines or ballistic missile defense – it might not be as well schooled in more basic skill sets like ship handling, said CSBA’s Clark.

“They have the most experience in these really challenging high-end missions, but they aren’t the best at all the stuff they don’t have time to do,” Clark said.

“I would argue that your general U.S.-based ship is probably better than your FDNF ships at basic navigation – like when you’re presented with unusual situations – because they’ve trained for everything.”

Navigation

At their core, the collisions of McCain and Fitzgerald were rooted in navigation and ship handling errors, according to the available information on the accidents.

Fitzgerald’s certification in mobility seamanship had been long expired at the time of the accident, in addition to all 10 of its warfare certifications, according to certification information obtained by USNI News.

The bridge crew of McCain lost control of the ship for almost three minutes before it was hit off of Singapore.

Loose outlines from both instances speak to lapses in navigation and ship handling fundamentals that can slip in the forward-deployed force, several officers have told USNI News.

While the U.S. Navy is the most technologically sophisticated navy on the planet, it doesn’t have the specialist emphasis on seamanship and ship handling compared to other navies.

Mitch McGuffie, a former U.S. surface warfare officer who served in an exchange with the U.K. Royal Navy for two years as a bridge officer, said that other navies place a higher value on navigation and ship handling than Americans.

“I was the go-to office of the deck on my first tour, and I thought I knew a lot of stuff. And then I went to the Royal Navy and I went through their navigator school, and it was the hardest class that I have ever gone through, with a 50-percent attrition rate,” he said.

British sailors specialize in a specific discipline at sea, unlike the U.S. surface warfare officers that are generalists. As a result, narrow specialties like navigation or bridge watches maybe given short shrift.

“People squeak through the system. They may be great officers and they may great engineers, but they might not have had a lot of time handling ships in busy waterways,” McGuffie told USNI News in an interview.

“We have guys that are commanding ships right now that have 400, 500 hours of bridge watchkeeping time in their career.”

In contrast, as the bridge officer on a Royal Navy frigate for a six-month deployment, McGuffie stood watch for more than 2,000 hours – all of them logged.

Royal Navy sailors, like U.S. naval aviators do with flight hours, note every bridge watch in a logbook throughout their career and are rigorously assessed throughout their career. U.S. surface officers have a certificate but no requirement for continuing training on navigation or ship handling, he said.

Even those certificates aren’t always required in the U.S. Navy. Ship handling and navigation certifications have often been delayed for FDNF forces with a so-called risk avoidance mitigation plan. RAMPs allow the ship to operate without the certification, the GAO found in examining the readiness of the FDNF forces.

Eight of the eleven warships operating as part of the FDNF had operated with lapsed certifications. In these cases, the RAMPs allowed the ship to deploy despite the expired or missing certification if a ship commander presented a plan on how the ship would attain that certification in the future.

In the case of Fitzgerald, at the time of the collision the ship had some certifications that had been lapsed for as long as 22 months.

Culture

While aviation and submarine forces have to meet minimum standards of certification and maintenance approvals before operations, surface force commanders have very little recourse if asked to go underway unprepared.

Decades of casualties in both the aviation and submarine communities led to the stricter standards of safety.

From 1949 to 1988, “the Navy and Marine Corps lost almost twelve thousand airplanes of all types (helicopters, trainers, and patrol planes, in addition to jets) and over 8,500 aircrew,” according a section of the book, “One Hundred Years of U.S. Navy Airpower” by Robert C. Rubel. In that period, the aviation community developed Naval Air Training and Operating Procedures Standardization (NATOPS), minimum sleep requirements, and an aggressive debriefing culture.

In 1963 the nuclear attack submarine USS Thresher (SSN-593) sank, killing all 129 hands onboard, and resulted in the creation of the submarine safety procedure called SUBSAFE, designed to get a submarine to the surface in the event of an emergency. Additionally, a submarine has training and maintenance standards associated with the nuclear reactor that allows very little flexibility for waivers and are well funded.

“In the surface community you don’t have a clear limit,” CSBA’s Clark said.

“You don’t have a clear quantifiable constraint, and it’s not as compelling to say this catastrophe was directly the result of shortcutting training or maintenance.”

The desire to find any way to complete a mission is part of the community, McFall said.

“The pride of the surface fleet is the ability to say ‘yes.’ [That many] warfare areas on one ship is insane. The ability to do all that on one ship is absolutely ridiculous,” he said.

“But the ability for, no matter what comes up, whether it’s [responding to a natural disaster, whether it’s missiles flying in the air, whether it’s a submarine that’s out there, whether it’s taking Marines somewhere – the surface community wants to say ‘yes, we can do that.’”

That can-do culture of risk-taking is a product of limited resources, retired Vice Adm. Tom Copeman, who served as commander of U.S. Surface Forces from 2012 to 2014, told USNI News

“You get the culture you pay for,” he said.

“I assert that the surface warfare culture is a result of the resource environment under which they have existed for a very long time and mostly ignored at the senior levels of the Navy.”

Since major training, maintenance and manning cuts in the early 2000s, “people were less trained and experienced than those before them, and they rarely had spare parts to fix what was broken, so when something broke it became the norm to operate that way. Get underway with the half the gear broken? No problem. We have an operational mission to meet,” Copeman said.

In 2013, Copeman gave a speech at the Surface Navy Association symposium warning the surface fleet was at risk of going hollow, which made waves in naval circles but didn’t resonate much beyond the service.

“Copeman stands up and says this is a problem, we got to say no, we got to stop deploying guys at the rate we are. It fell on deaf ears because it’s the boiling frog problem, unlike the other communities where there is a hard limit you run up against,” Clark said.

Maintenance

A major stressor on surface readiness was the inconsistent maintenance of the surface ships. Navy aviation and nuclear-powered carriers and submarines have minimum standards each plane, carrier and sub have to meet in order to be approved for operations – something not found in the surface force.

The looser rules, combined with the demand on forces as the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq heated up in the early 2000s, created additional lapses in repairs.

Around 2010, after a decade of getting by, the Navy started to make strides to correct the issues and reform how surface ships were fixed but found looming challenges after almost decade of neglected maintenance.

The effort became harder still following the implementation of the 2011 Budget Control Act, which put hard spending caps on defense budgets that disproportionately affected operations and maintenance accounts. That, combined with extended continuing resolutions, prevented the Navy from starting new availabilities on time.

“All of those put pressure on surface maintenance, and that pressure could be manifested into two words: stability and predictability,” former-CNO Adm. Jonathan Greenert told USNI News earlier this month.

“That was, in a nutshell, our biggest challenge in that area.”

For the sailors on the waterfront, longer maintenance availabilities created a difficult atmosphere to stay current on training. Repair hang-ups also meant crews on healthier ships were out longer when deployments were extended, and that sometimes needed work was skipped to help make up the time, making it harder for sailors to keep all their systems operational.

“Depot and intermediate maintenance were so wildly behind, it is almost too hard to fix at this point,” former SURFOR Copeman told USNI News.

“Ships go double to three-times the time suggested for major events such as dry-docking, tank work and all sorts of unglamorous but critical work that needs to be done.”

Training

Compared to the two other major warfighting areas in the Navy – submarines and naval aviation – officers in the surface warfare receive a fraction of the training before they report to their first ships.

A Navy pilot trains for two years before being assigned to his first squadron, while a submarine officer spends an equivalent time in nuclear reactor school before arriving at their first boat.

Until 2003, the Surface Warfare Officer School Division Officers Course (SWOSDOC) gave fresh ensigns 16 weeks to learn the basics before reporting to their first ships.

But SWOSDOC was eliminated, and instead of easing into the role through classroom instruction, ensigns were expected to learn the basics of their job while on the job – aided by a computer-based course to be taken aboard ship, in addition to their regular duties.

In 2012, the Navy reinstituted an eight-week course to teach the basic rules of the road before ensigns report to their first ship. The Navy also created an eight-week course for officers set to go to their first department head tour in a later deployment.

Pilots are required to have an extensive qualification period after shore duty before returning to the fleet, but surface warfare officers don’t have the same level of refresher courses and can spend up to four or five years on shore before reporting to a new ship as the executive officer. In order to mitigate some of the time away, the service implemented the “fleet-up” program in 2006 in which the executive officer would succeed the commander to provide more consistency in surface leadership.

“A commanding officer will reap the benefits of the actions and policies he or she institutes as executive officer. He or she will know the crew upon assumption of command and will be intimately familiar with the material condition and the combat readiness of the ship,” read a statement from the service at the time.

Subsequent Navy reviews found the program had a mixed record of success.

The Balisle Report

This week Commander of U.S. Fleet Forces Adm. Phil Davidson is expected to release a full report examining the underlying issues that contributed to the collisions of Fitzgerald and John S. McCain. While the Davidson review is the latest look into how to fix the surface forces, it is by no means the first.

In 2009, a string of poor results in ship inspections prompted Fleet Forces and U.S. Pacific Fleet leadership to commission an independent look at the health of the surface force.

The year before, six warships failed their congressionally mandated Board of Inspection and Survey (INSURV) event, and more than two dozen ships had critical failings in the material condition of the ships and crew training.

The commands tapped former Naval Sea Systems Command head Vice Adm. Phillip Balisle to lead a panel to investigate, which resulted in an extensive and damning report on the health of the surface fleet.

“The material readiness of the surface force is well below acceptable levels to support reliable, sustained operations at sea and preserve ships to their full-service life expectancy,” read the summary of what is now known as the Balisle Report.

“Material readiness trends develop and evidence themselves over years vice months. The causes and effects, bad or good, are not quickly realized. Accordingly, the effective material readiness program is one that is consistently followed with small, evolutionary improvements made to it vice dramatic changes.”

The panel cataloged the reduction of manning on ships, reduction and deferral of maintenance, the dilution of training, and problems in command and control as all part of a cycle of readiness that had been slowly eroded since the end of the Cold War.

The goal of those changes – which began to snowball at the turn of the century – sought to find a readiness baseline that held a minimum standard of military effectiveness at the maximum amount of cost efficiency. However, the choices made in the 2000s went too far, concluded the study.

“The Balisle Report was a very good assimilation of the various things that had been troubling the surface community from the perspective of the material condition of the ships – it was more than maintenance,” Greenert told USNI News earlier this month.

“It was all in one place that these are the various challenges that were going on, and that was very useful.”

The Way Forward

Former Under Secretary of the Navy and Deputy Secretary of Defense Bob Work told USNI News that, in his eyes, there was a simple reason for all of the problems with the surface force.

“To me, it’s a very simple problem. It’s a problem with saying no,” Work said.

“Everybody knows what this problem is, and it pisses me off that we don’t get after it. Everyone says you need 355 ships to meet all the minimal requirements of the COCOM (combatant commander) because the COCOM demands are unconstrained. We have 276 ships, so you have a choice: you either can try like heck to hit as many of the missions of a 355 (ship navy) with the 276 ships that you have and run the Navy into the deck, or you can say you have 276 ships and we will apportion the presence and prioritization you need but we will keep the fleet intact and ready to fight. ”

He said that the un-moderated demand from combatant commanders asking for forces are straining not only the surface navy but also the military as a whole.

Work said the argument for more deployments– it gives the U.S. more visible presence on the sea and around the world – is overstated, and that having a smaller but deadlier fleet was the best course of action for the service rather than a stressed and poorly ready force prone to accidents.

“The U.S. Navy is the best navy in the world, and we want everyone to think it’s the baddest navy in the world, and these types of accidents undercut that mythology that the U.S. Navy is the single superpower navy and screwing around with them is not a good thing,” he said.

“To me, having everyone thinking the U.S. Navy is the peerless warfighting fleet on the planet – and if they try something the Navy will get there and beat the snot out of them – is the best way to have deterrence.”