ANNAPOLIS, Md. — The Navy and Marine Corps are committed to using alternative platforms to move Marines around at sea, but there are still decisions yet to be made about how to maximize these ships’ effectiveness and minimize risk while operating independently or as part of a strike group.

Director of Amphibious Warfare Maj. Gen. David Coffman (OPNAV N95) told reporters last week that, with the first Expeditionary Sea Base now operating in U.S. 5th Fleet and potentially available for Marines in the area, “the Marine Corps position on it is two-fold: first is an absolute commitment to L-class amphibious warships as the centerpiece for amphibious operations, and the way to embark a Marine Air-Ground Task Force (MAGTF) for contested environments. But, recognizing that the capacity challenge for that and trying to get to a lot of places, that in particular segments of the range of military operations these so-called alternative platforms” would be a useful option for regional commanders.

The Navy has 31 amphibious ships today, but the Marines say they need at least 38 ships, and potentially upwards of 50 to fully meet combatant commanders’ needs.

Coffman spoke at the National Defense Industrial Association’s annual Expeditionary Warfare Conference. After a panel that discussed USS Lewis B. Puller (T-ESB-3), which was built primarily to support mine countermeasures operations and special operations forces, Coffman told reporters that the Expeditionary Sea Base could also help move the land-based Special Purpose MAGTF- Crisis Response unit in U.S. Central Command, or supplement an Amphibious Ready Group operating in the Persian Gulf, or more.

“Clearly the idea is, spread out these variety of platforms – work on how you fill forward-deployed, forward-engaged and crisis response (missions) with Amphibious Ready Group formations, and then use ESBs either as fillers or in support of” those ARGs, he said on Oct. 24. He said that, while the Navy, Marine Corps and joint force had not made any decisions yet on exactly where or how to employ Puller as that ship finds its place in the fleet, he noted that the services are already looking to have more ESBs.

“The idea though, if you get the buy right, is you’d have enough to hit all the key spots you would expect to put them in terms of how we surround Eurasia from the Med, and CENTCOM, and Western Pacific, and you’d have them against all of the major challenge sets,” he said.

“We’re looking at a ship that could host MCM, irregular warfare with SOF, Marines, coalition partners, et cetera et cetera et cetera.”

Still, he said, many logistics have not been worked out, in part due to uncertain funding and an unclear acquisition profile beyond the third ESB, which is currently being built at General Dynamics NASSCO in San Diego and set for a spring 2019 delivery. Some lawmakers are interested in procuring a fourth ESB in the Fiscal Year 2018 budget, though there still isn’t consensus among the four defense committees about moving forward on the ship this year.

“I’m not saying Puller snuck up on us” in terms of not knowing how to operate the ship in theater, he said, but “back to the discussion of, how about some stability in these programs? Then we say, okay, I’m going to get X number of these, I’m going to get them in these increments, and here’s how I’m going to deploy them, here’s what I need to spend to put [command, control, communications, computers, combat systems and intelligence] systems or optimize them, and then you get a better plan, instead of, oh boy, where does this one go and what do we do with this thing tomorrow? So we definitely – and that’s the big We – could get more purposeful in how we apply them.”

As the services make those decisions on how to outfit and employ ESBs and other alternative platforms, including the Expeditionary Fast Transport (EPF) and other Military Sealift Command-operated ships, Coffman said a discussion needed to be had on the risk associated with operating Marines off a ship not designed to sail into a contested environment.

He said the commandant of the Marine Corps and the chief of naval operations are enthusiastic about using these ships to mitigate an amphibious ship shortfall, but “to be frank, I frequently find myself advocating not against them, but just stronger on the caveat because I grew up on L-class amphibious warships, I’ve commanded [Marine Expeditionary Units] and [Marine Expeditionary Brigades] that operate on all of them, and I’m just telling you there’s nothing in the world, nothing in the world that can do what our L-class warships can do,” Coffman said.

“To do so, you have to build to those [military specifications], you’ve got to do them that way. So just my personal view on that, [alternative platforms] will always be something less than that. Then we figure out – and this is back to the art and science of war – then we figure out how to apply that.”

He said that in a naval battle, ships would be coming and going from the theater and that perhaps ESBs and EPFs could contribute up to a certain threshold of risk in the operating environment, but given the fluidity of naval battle “it’s going to require an agility to our application of assets more than we have seen before.”

Coffman again referred to agility when telling reporters that regional task force commanders shouldn’t look at ARGs and other strike groups as a single entity, but rather should look at all afloat and ashore assets holistically and consider how they could be paired up to meet operational needs.

Several other speakers brought up items to consider as the Navy and Marines look at alternative platforms going forward.

During a panel discussion, Capt. John Moulton, who works on Coffman’s staff as the head of the Navy Expeditionary Combat Branch (OPNAV N957), noted the importance of allowing operators to practice before being asked to work off a new class of ship in theater.

“If you really want to be smart about it, it’s got to be part of our workup cycle, our Optimized Fleet Response Plan,” so that Marines and sailors can practice on these types of ships at home, during pre-deployment training and in theater throughout deployments.

Deputy Commandant of the Marine Corps for Plans, Policies and Operations Lt. Gen. Brian Beaudreault noted this year’s USS Fitzgerald (DDG-62) and USS John S. McCain (DDG-56) collisions and wondered how an event like that, or a mine or torpedo attack, would play out on an alternative platform, which is not build with the same survivability standards as a warship.

“The ability to save lives, save the ship, do damage control, carry on with the mission; I’m concerned,” he said, noting “it’s a double-edged sword on the use of alternative platforms for a mission that’s better called for by an amphibious ship” – with the service needing to get more Marines to sea but also needing to do so with acceptable risk.

Beaudreault said he wasn’t arguing against putting Marines on alternative platforms, but rather suggested that risks are inherent in doing so and should be considered by operational planners as they look at how to integrate Puller and other ships into the fleet.

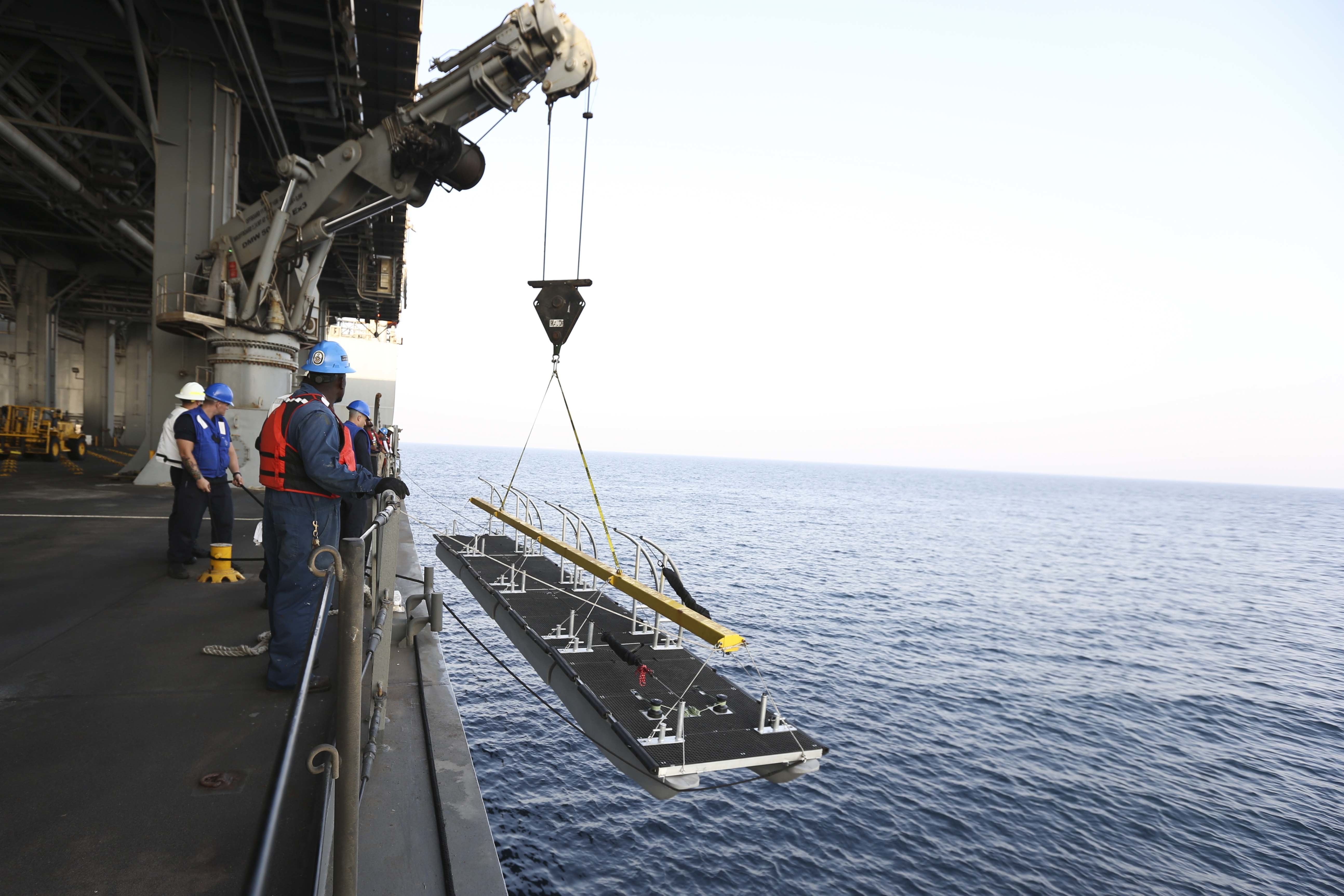

So far, Puller arrived in U.S. 5th Fleet in August and was redesignated a USS warship, instead of a USNS ship, to allow 5th Fleet more operational flexibility. Since that time, Capt. Michael Egan, Commander of Task Force 52 in U.S. Naval Forces Central Command, said at the conference, “a month after she got there we immediately put her to her trials by sending her down to the Djibouti area down there with different capabilities embarked and trying to just shake her out. It’s actually looking quite well,” Egan said, but the ship’s crew and CTF 52 are collecting information on what capabilities might be improved or added down the road to better meet operational needs.