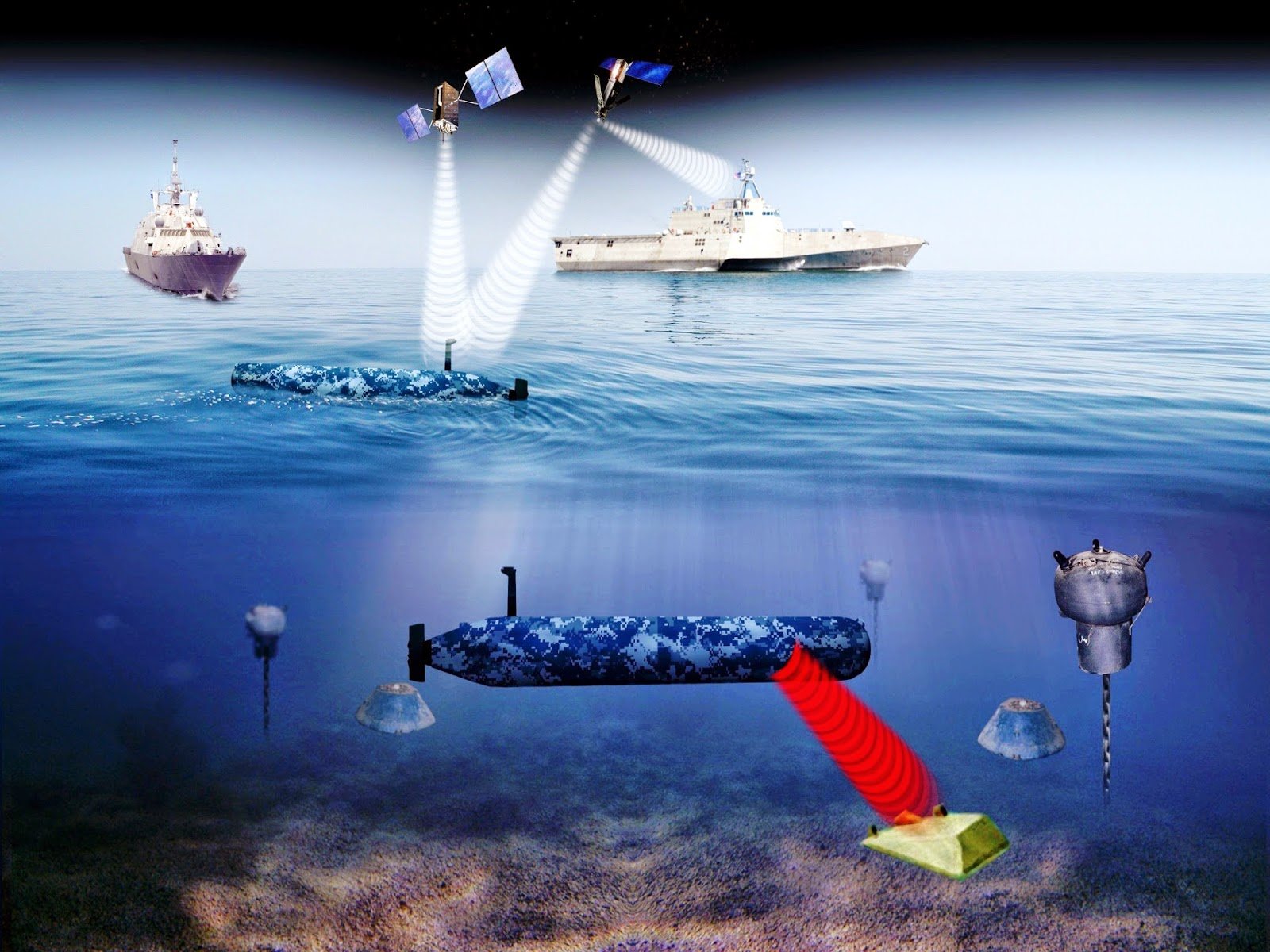

With unmanned vehicles integral to the future of the Littoral Combat Ship, the Future Surface Combatant and the next-generation SSN(X) attack submarine, the Unmanned Maritime Systems Program Office is testing as many unmanned vehicles – both programs of record and prototypes alike – as fast as it can to learn lessons and field systems to the fleet.

Capt. Jon Rucker, the unmanned maritime systems program manager (PMS 406) within the Program Executive Office for Littoral Combat Ships, told USNI News in a recent interview that he’s had the ear of the chief of naval operations, the resource sponsors at the Pentagon, researchers and engineers at warfare centers and systems commands, and industry as he’s pushed to develop unmanned maritime systems and integrate them into how the Navy operates.

Among the programs in the portfolio furthest along in development is the Knifefish unmanned underwater vehicle, which will detect and classify buried mines and mine in high-clutter environments. That system wrapped up contractor trials in late August, and initial factory acceptance testing was completed last week, Rucker said. Sea acceptance trials, which are the final contractor-led tests, will take place at the end of October, and the Navy will follow that up with its own formal developmental test and operational assessment.

Also in the LCS mine countermeasures mission package is the Common Unmanned Surface Vehicle (CUSV), which will pull a minesweeper in its role as the Unmanned Influence Sweep System (UISS). That craft is in the middle of contractor testing in South Florida now, and Navy testing will begin after the contractor testing wraps up. CUSV will also be evaluated for a role in mine-hunting missions, which will require its own schedule of contractor- and Navy-led tests.

On the undersea warfare side of the portfolio, the Navy’s Large Displacement UUV (LDUUV) and Extra Large UUV (XLUUV) have both made recent progress as well.

The Snakehead LDUUV completed a preliminary design review on Sept. 12 and is now in the detail design phase. The program is ramping up manning and aiming for a critical design review in the first quarter of Fiscal Year 2019, assuming the program is fully funded in the FY 2018 budget, Rucker said.

The Orca XLUUV is in source selection and is on track to award an initial design contract in the last week of September.

Prototypes and Experimentation

In addition to these programs of record, the Navy and Marine Corps have been testing as many unmanned vehicle prototypes as they can, hoping to see the art of the possible for unmanned systems taking on new mission sets. Many of these systems being tested are small surface and underwater vehicles that can be tested by the dozens at tech demonstrations or by operating units.

The ADARO small unmanned surface vehicle, for example, is still in the initial development stage but is being tested by Naval Surface Warfare Center Combatant Craft in Norfolk. This vehicle, developed under the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program, is about three feet long and could assist special operators, explosive ordnance disposal technicians or Marines.

“If you look at the special forces guys, they’re looking for something that they can plop in the water quickly to be able to go do reconnaissance or other communications-type things they want to do,” Rucker said.

“So this particular craft – just like anything we put in the water first, the company developing it improved the engines, improved the efficiency, got it to be a little more watertight so if it hits a wave it flips over and rights itself – they improved all that. So they’re at a stage now where they have a few out there and they’re going through testing with the small business, with the special forces guys” to see if NSWC-CC would want to use its funding to continue with that product.

Rucker said a lot of the small unmanned vehicles are used to extend the reach of a mission through aiding in communications or reconnaissance. None have become programs of record yet, but PMS 406 is monitoring their development and their participation in events like the Ship-to-Shore Maneuver Exploration and Experimentation Advanced Naval Technology Exercise, which featured several small UUVs and USVs.

“I would anticipate down the road there being a need” for a vehicle like that and the transition of at least one or two to a program of record, but for now Rucker said the systems need to prove not only that they work but that their success is repeatable in an operational environment.

On the UUV side, Rucker said his office is working with the Expeditionary Missions Program Office (PMS 408) at Naval Sea Systems Command and the Battlespace Awareness and Information Operations Program Office (PMW-120) at the Naval Space and Warfare Systems Command on a collection of small and medium UUVs that can do sea sensing, oceanography, mine countermeasures and more. For one small vehicle, the Iver, the Navy has 50 or 60 of the UUVs at its unmanned squadron (UUVRON-1) in Keyport, Wash., for testing concepts of operations, developing tactics and training.

Future Manned-Unmanned Teaming

Even as unmanned system prototypes are tested today with the hopes of procuring those that may fill a capability gap, the Navy has a longer-term reason to continue testing these unmanned systems: several of its future ship classes will rely on unmanned systems, by design, to fulfill their missions. The Littoral Combat Ship was designed around being a mothership for unmanned vehicles in several warfare mission areas. The Future Surface Combatant will include a large manned combatant, a small manned combatant, and a family of unmanned surface vehicles. And the SSN(X) – the attack sub planned to come after the Virginia class – will rely on UUVs to extend its reach.

“Going forward, no UUV any time in the near future is going to replace a manned system. The capability of a submarine is just not matched by one of these,” Rucker said.

“However, with submarines, the number we have isn’t what we want in terms of total number, so if you can augment the submarines and have a manned and unmanned platform working in concert, or helping with some of the easier, more repetitious missions, you can unburden the submarine to do some of the other capabilities we need it to do.”

He said the Navy isn’t waiting for the start of SSN(X) to learn how to do this. The next increment of the Virginia class, the Block V design for which a request for proposals went out to industry last month, will ensure the submarine and the Snakehead UUV are compatible, to begin to pave the way for SSN(X)’s manned-unmanned teaming.

“The SSN(X) of the future, as they go forward with that design, everything that they’re looking at is taking unmanned into account, because going forward that’s something that a submarine will need to be able to do – not only its normal missions, but be able to act as a large ocean interface to support unmanned vehicles,” Rucker said. All the interfaces will be defined so that developers can build unmanned vehicles or payloads that are inherently compatible with the submarine – a process being started now with the Virginia-class/Snakehead integration.

On Future Surface Combatant, Rucker said he’s working closely with the surface warfare directorate at the Pentagon (OPNAV N96) to understand the timeline of the program, but he said wargames and workshops this year validated the need for a family of unmanned surface vessels to be included in the FSC concept. The FY 2019 budget cycle will likely yield more answers, he said, but he explained that two ongoing USV projects today will be integral in teaching PMS 406 what the unmanned piece will look like.

ONR now controls the first Anti-Submarine Warfare Continuous Trail Unmanned Vessel (ACTUV) vehicle, since renamed the Medium Displacement USV (MDUSV) and also called Sea Hunter. The 2017 budget included funding to build a second vehicle. Rucker said ONR is testing the first vehicle in San Diego, buying down risk for the operational navy as they learn how to operate an unmanned surface craft while adhering to the rules outlined in the Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (commonly known as COLREGS), for example. Additionally, a Pentagon-led effort called Ghost Fleet is testing a larger USV with additional payloads that Rucker said he could not discuss. But both efforts would be important, he said, because Future Surface Combatant may likely end up with a family of two USVs to fill the unmanned portion – a smaller USV similar to MDUSV, about 100 to 150 feet long, and a larger one akin to Ghost Fleet, at about 200 to 250 feet long with greater payload capacity.

“Those craft, from an endurance, speed, payload capability, they’re quite different,” he said, adding that having both would give surface warfare officers great flexibility in conducting missions at sea.

“From these two, as they learn, they’re going to kind of gauge from the ACTUV, the Sea Hunter, and the Ghost Fleet, they’re going to take those – and in parallel be developing requirements that we learn from that – to then decide this is what we want to go buy,” he said of the Future Surface Combatant effort.