On May 17, 1987, the Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigate USS Stark (FFG-31) was on patrol when it was struck by two Iraqi Exocet missiles in the midst of the Iran-Iraq War.

The missiles were fired from an Iraqi Dassault Mirage F1 by a pilot who thought the U.S. frigate was an Iranian tanker.

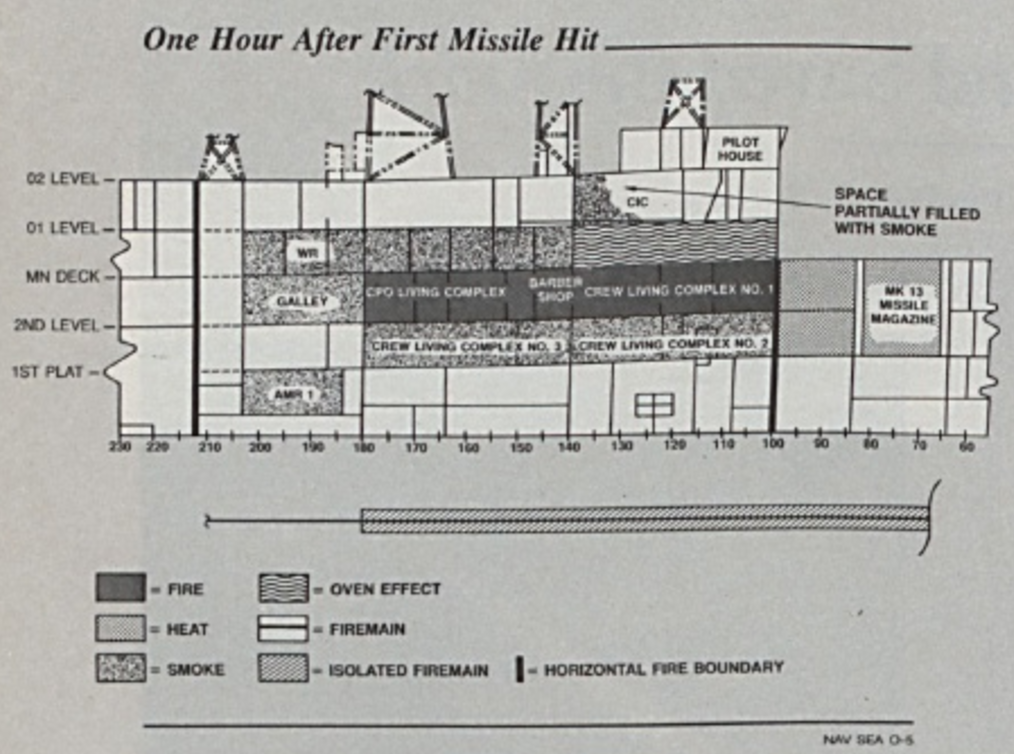

“The first missile punched through the hull near the port bridge wing, eight feet above the waterline. It bored a flaming hole through berthing spaces, the post office, and the ship’s store, spewing rocket propellant along its path. Burning at 3,500 degrees, the weapon ground to a halt in a corner of the chiefs’ quarters, and failed to explode,” wrote Brad Peniston in his book No Higher Honor from the Naval institute Press.

“The second missile, which hit five feet farther forward, detonated as designed. The fire burned for almost a day, incinerating the crew’s quarters, the radar room, and the combat information center.”

Thirty-seven sailors died as a result of the missile strikes and the ship was sidelined for repairs for more than a year.

The following are material from the U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, Naval Insitute photo archives and oral histories on the Stark incident and its aftermath.

Rear Adm. Harold J. Bernsen, USN

Commander Middle East Force from 1986 to 1988

Oral History Excerpt

Between the period of ’80 to ’85, there was relatively little activity at sea, as I recall. But that began to change as the Iraqis sensed that one way to put pressure on the Iranians was if they could curtail the flow of oil out of Iran onto the world market. Almost all of the Iranian export capacity was funneled through Kharg Island—not all of it but almost all of it—in the northern part of the Gulf, just to the east of the Shatt al-Arab. So the Iraqis began to concentrate on interrupting the flow of shipping that carried that oil from Kharg Island down the Gulf and out through the Strait of Hormuz to other world ports. They did this by attacking Iranian and other world shipping that was carrying Iranian crude. They did it primarily by attacking those ships in the so-called Iranian self‑proclaimed war zone, extending to the south from the coast of Iran and encompassing almost half of the Persian Gulf.

In retaliation for those attacks, the Iranians, in turn, had decided to attack ships also. But since the Iraqis did not have any ships in the Gulf, in the vicinity of the Gulf, the Strait of Hormuz, or in the Gulf of Oman, the only targets that the Iranians could strike were those which consisted of ships transiting the Gulf and the strait, in trade with the Gulf Arabs, all of whom by definition were allies or at least in one way or another in support of the Iraqis.

So you had in essence two quite different anti-shipping regimes, but regardless of the basic difference in the two, the overall result was the same: a Gulf that was confused, frightened, a war zone. There was not a great deal loss of life, but an awful lot of economic destruction, and a really confused and a rather perilous area, particularly if you were a commercial shipper…

We were sitting at dinner when the watch came down from the war room and informed me of a report from the Air Force AWACS that was flying out of Saudi Arabia. The report was that an Iraqi aircraft had been detected and was coming south out of Iraq. That was not unusual. I won’t say it was normal but almost normal.

They would come down from Baghdad and the airfields around Baghdad and skirt the western edge of the northern Gulf. Then at some point, which we surmised was a point where they detected on their air-to-surface radar a shipping contact, presumably Iranian, along the Iranian coast to the east, they would then turn east and launch a missile at that contact.

There was no identification procedure that was followed. It was simply a blind shot. The fact is on many occasions they actually hit. These were Exocet missiles, and they actually were able to strike the target. The Exocet is an extremely good missile, and the French had supplied the Iraqis with a good many of them, and they were practiced in their use.

‘The Stark Report’

by Michael Vlahos

Proceedings, May 1988

The Stark’s commanding officer. Captain Glenn R. Brindel was informed of the lraqi aircraft`s presence by at least 2005, when the aircraft was about 200 nautical miles away.

Lieutenant Basil E. Moncrief was on watch in the Stark‘s combat information center (CIC), serving as tactical action officer (TAO). Captain Brindel stopped in the CIC at about 2015 and was reminded about the Iraqi aircraft.

On the bridge at 2055, Captain Brindel asked why there was no radar picture of the Iraqi aircraft. The CIC responded by switching the SPS-49 air-search radar to the 80-mile mode. The aircraft was acquired 70 miles out at 2058.

Lieutenant Moncrief was informed that the aircraft would have a four-nautical-mile closest point of approach (CPA) at 2102. Also at 2102, the radar signature of the Mirage’s Cyrano-IV air-intercept radar was detected, anti for several seconds the radar locked on to the Stark. At 2103, the SPS-49 operator requested permission from Lieutenant Moncrief to transmit a standard warning to the F-1. Moncrief said, “No, wait.”

Two minutes later, at 2105, the F-1 turned toward the Stark at 32.5 nautical miles out. It was on a virtual constant bearing, decreasing range, but this move was missed by the Stark‘s CIC. The first missile was launched at 2107, 22.5 nautical miles from the Stark.

The forward lookout saw the missile launch, but it was first identified as a surface contact. Lieutenant Moncrief finally observed the F-1 course change at 2107. Captain Brindel was called, but could not be found.

The weapons control officer (WCO) console was manned, and at 2108 the Stark contacted the F-1 on the military air distress frequency, requesting identity. At that moment, however, the Iraqi pilot was firing his second Exocet. The electronic warfare technician at the SLQ-32 console heard the F-1’s Cyrano-IV again lock on to the Stark. The lock-on signal ceased after seven to ten seconds. Permission was given at this time to arm the super rapid blooming offboard chaff (SRBOC) launchers. A second warning was radioed to the F-1 at about 2108, and the Stark‘s Phalanx Gatling gun was placed in “standby mode.”

At 2109, the Stark locked on to the F-1 with her combined antenna system. The lookout reported an inbound missile to the CIC, but the report was not relayed to the TAO.

Lt. Art Conklin, USN

Stark’s damage control assistant.

‘We Gave a 110% and Saved the Stark’

Proceedings, Dec. 1988

At approximately 2112, l heard the horrible sound of grinding metal and my first thought was that we had collided with another ship. I immediately opened my stateroom door and headed for Damage Control (DC) Central. Within a fraction of a second I knew we were in trouble. I smelled missile exhaust and heard over the 1MC, “inbound missile, port side… all hands brace for shock!” Then general quarters (GQ) sounded and I saw the crew move faster than they ever had before. The first missile had slammed into the ship under the port bridge wing, about eight feet above the waterline. It’s speed at impact was more than 600 miles per hour. The warhead did not explode, but the missile did deposit several hundred pounds of burning rocket propellant as it passed through passageways, berthing compartments, the barbershop, post office, and chief petty officer quarters. And although we did not know it at the time, the missile still had most of its fuel on board, since it had traveled only 22 miles from me launching aircraft to our ship.

The potent mix of the missile’s fuel and oxidizer resulted in fires hotter than 3,500° Fahrenheit that instantly ignited all combustibles and melted structural materials. This temperature was nearly double the 1,800° normally considered the upper limit in shipboard fires.

About 30 seconds later, the second missile struck the Stark eight feet forward of the first missile’s point of impact. It traveled only five feet into the skin of the ship and then exploded with a tremendous roar. Later analysis determined that the damage, while significant, was not as great as might have been expected because a large portion of the blast’s effect was vented away from the interior of the ship, creating a huge, gaping hole in the process. This reflects the results of the ship’s strong [Damage Control] preparation.

Within minutes, nearly one-fifth of the crew had been killed and many others had been overcome by smoke, bums, and shrapnel wounds. The remaining crewmembers had a monumental task ahead of them, yet they plunged ahead.

I witnessed countless acts of heroism throughout the night: Electronics Technician Third Class Wayne R. Weaver III sacrificed his own life to assist many crewmembers to safety from the primary missile blast zone. Seaman Mark R. Caoutte, despite severe burns, shrapnel wounds and the loss of one leg, continued to set Zebra in an area being consumed by fire. Gunner`s Mate Third Class Mark Samples risked his life for 12 hours, spraying cooling water inside the ship’s missile magazine. Had it exploded, the Stark would have gone to the bottom. Thanks to the intensive first-aid training given to the crew, Mess Management Specialist Second Class Francis Burke was directly responsible for resuscitating many smoke inhalation cases. Many other heroic acts were performed, but they all had a common thread: In each of these cases, the crewmembers acted correctly, using their training to solve a complex casualty.

Adm. Frank Kelso, USN

Chief of Naval Operations 1990 to 1994

Commander in Chief, U.S. Atlantic Fleet 1986-1990

Oral History Excerpt

As you said, one major event that happened during my time at CinCLantFlt (Commander in Chief Atlantic Fleet) was the Stark getting hit accidentally by an Iraqi aircraft-launched missile. The Stark tragedy was a very difficult event to understand why it occurred, and it created the worst of tragedies for the families involved. We learned many new lessons from the Stark about the changes that were taking place in the operation of deployed ships in a changing world.

I remember getting a phone call that said the Stark had been hit in the Persian Gulf. They thought there might be a few injured and maybe one dead. And, of course, the news that the Stark had been hit came immediately over CNN. And I really wasn’t prepared for how to deal with such a casualty in the modern world of instant media notice.

Of course, what happened then was that every dependent, mother, father, that had anybody related to them on the Stark started to call to find out what happened on the Stark. And at that time we didn’t really know what had happened on the Stark…

I think if I had to do it over again I would have told them, “This is what I know,” at any particular time during the period of time. It took a period of two or three days for this thing to sort out, and the total toll was 37 dead before it was over. It is not unusual for the true results to be slow to determine. Both the Stark and the other ships in the area did a magnificent job of fighting the fire and saving the ship when you look back at it. But a tragedy like that is very difficult to deal with.

Rear Adm. Harold J. Bernsen, USN

‘As I Recall – Assault on the Stark’

Naval History Magazine June 2017

The investigation began rather quickly. When 37 people die, the Navy gets disturbed. Within a very few days, Rear Admiral Grant Sharp and his team flew to Bahrain. The investigation, as I recall, went on for some ten days, maybe even a bit longer. Just before he left the ship, he said: “We’re finished. We’re going to go home, and we’re going to write this thing up.”

I had the temerity to say, “Grant, I don’t know if you’re allowed to say this, but how did we come out here on the staff, because I am concerned?”

He said: “I had no problem with your actions or the actions of your staff. The preparation and the briefings provided to the skipper of the Stark were appropriate and in my view sufficient for him to have taken the proper action.” That was reassuring.

Now, what really happened? This is the disturbing part. It seems that when Captain Brindel got back to his ship after the morning briefing on the flagship, he did not gather his key people together and go over with them the events that had occurred on board the Coontz. In the interviews during the investigation, he maintained over and over that he was so focused on the need to conduct a series of engineering drills for his superiors back in the United States that the rest of the mission came second.

I guess it was a young lieutenant down in CIC who didn’t want to make waves. He didn’t want to get up on the radio and tell anybody anything, so the airplane just flew down their throats. I really fault the skipper. Other people could have done something to prevent this, but it really emanated in this case from the top. A terrible tragedy, but it just shows what a lack of priorities and command attention can do.

The whole thing was a sad situation. The most moving day of my life was on the tarmac at Bahrain International Airport, when each of those 36 flag-draped coffins moved up the ramp on that C-141 for the flight home. (One crewman who went into the sea was not recovered.) Of course, what goes through your mind at that point, regardless of what the hell any investigation says, is, ‘Was there anything else that we could have done that might have avoided this goddamn thing?’

It will always be a sick feeling.