This post has been updated with additional information on the intellgence findings that informed U.S. leaders’ decision to carry out the attack on Thursday.

THE PENTAGON — Senior U.S. defense officials today briefed reporters on the planning and execution of a Tomahawk strike on al-Shayrat Airfield in Western Syria Thursday night, which involved two guided-missile destroyers launching 59 missiles at targets.

The U.S. strike comes after an April 4 chemical weapons attack on the town of Khan Sheikhoun, where several dozen civilians, including many children and women, were killed by what appears to be sarin gas.

The following is a timeline of the April 4 attack and the decision process of U.S. leaders leading up to Thursday’s strike.

The Strike

- “Shortly after the attack, the following day on the fifth, the president directed the Secretary of Defense to come up with military options in response to this attack,” a senior defense official told reporters this morning at the Pentagon. “We came up with military options on the 5th; those options were basically put together into recommendations. It went forward to the National Security Council, multiple meetings with not only the presidential senior advisors but also with the Chairman, the Vice Chairman, the Secretary of Defense. Interagency members deliberated, looked at the proposals on the 5th, and then on the 6th of April those proposals were presented to the president.”

- The official said that all the options presented to President Donald Trump were also sent to U.S. Central Command, and to destroyers USS Porter (DDG-78) and USS Ross (DDG-71), to begin preparing for any potential decision.

- “During that planning period, all the forces, in this case the two ships, had basically options, and then all they had to do was, we just had to tell them the presidential-picked option. And that helps speed up that execution,” the official said. “We prepositioned forces so that if there was an order received we could have that quick response. … So by the time the options were given to the president, we were in position to execute upon order. And so when the order was given and passed along to the commander, forces were in position in order to launch the missiles.”

- On April 6, Trump selected the Tomahawk Land Attack Missile strike option, which military officials have described as both “proportional” but also “our lowest-risk option to conduct the attack” due to the standoff range they allow. Russian military forces operating in Syria have sophisticated integrated air defense systems, and officials did not want to send manned fighters into harms way – though the Russians ultimately did not attempt to intercept any of the TLAMs coming towards the Syrian airfield.

- “The president decided on an attack on the al-Shayrat Airfield as the military option. That process was made in the National Security Council yesterday afternoon (on April 6),” the official told reporters. “We got orders from the president around 4:30 yesterday afternoon, who directed the Secretary of Defense and passed down to the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff down to the [U.S. Central Command] commander to execute those orders. Four hours after those orders were received, there were 59 TLAMs that were launched and hit their target at approximately 8:40 yesterday evening Eastern Standard Time.”

- “We developed a proportional response option for the president, which included military response option targets. And what I mean by that are those that are encircled (on initial damage assessment images) – so a military response target would be hardened aircraft shelters, aircraft, fuel that would go into the aircraft, munitions that go into the aircraft, anything that would be a part of a military operation was part of the target area.”

- “Between the two of them (Ross and Porter), they launched this salvo of 59 missiles. And we have, with positive confirmation, that each one of those missiles hit the target.”

- Targets included various aspects of Syrian regime capabilities – but they steered clear of known Russian assets, including rotary wing aircraft, facilities for between 20 and 100 Russian military personnel and more.

- “It’s a fairly large airfield – that runway is almost 10,000 feet long and you can see there are multiple spider webs … at the end of the runway (that) are hardened aircraft shelters. Also located around this airfield are petroleum and fuel storage areas. Also there’s known chemical storage bunkers, and there’s also surface-to-air self-defense missile systems that are on the outskirts of this airfield.”

- The defense official said that initial damage assessments show that all 59 targets were hit, though it is impossible at this point to verify that all the planes that had been inside the hardened aircraft shelters were still there at the time of the attack and were destroyed. Officials are calling the damage “about 20 aircraft,” all of them Russian-made and Syrian-operated fixed-wing aircraft – including those that were involved in the April 4 chemical attack. The runway itself was not targeted – the TLAM, based on its size and capability, would have had little impact on the runway and would be “a waste” for that target set, a senior defense official said.

- The timing of the attack – around 3 a.m. local time, was chosen to avoid any potential civilian casualties, though the official said there are no towns or homes near the airfield. The official added that there was no indication of civilian or military casualties at this point.

Why Use Tomahawks, Destroyers?

Earlier this month, the head of U.S. Strategic Command spoke in praise of the U.S. Navy’s surface fleet as his preferred method of conventional strike in a crisis.Air Force Gen. John Hyten said strikes from surface ships – versus submarines or bombers – offer an unambiguous message when the U.S. chooses to use force in a conflict.“The surface Navy provides options,” unavailable from other platforms,” he said speaking at the Military Reporters and Editors conference in Washington, D.C.

“We can put those ships where we want them.”Thursday’s strike from USS Ross (DDG-71) and USS Porter (DDG-78) was the largest TLAM employment since 2011’s Operation Odyssey Dawn from ships that are primarily tasked with ballistic missile defense missions. While BMD is their primary role, the ships were able to quickly prep for the strike using the same vertical launch cells — 90 on each ship — that hold anti-air missiles and BMD interceptors to launch TLAMs.“These platforms provide an option for the leadership for a measured and deliberate strike. That’s their value,” Capt. Paul Stader – former commander of USS Hue City (CG-66) and USS Ross (DDG-71) — told USNI News on Friday.

“[Tomahawks] are very short notice and are capable of executing within a very tight timeline. They’ve evolved over the years that we’ve had them in the inventory and they’re a very capable option for leadership if we want them. “–Sam LaGrone

The Intel

A second senior defense official explained to reporters the background of the air strikes, as the U.S. has watched the Syrian regime escalate its chemical-related attacks on its own civilians in recent weeks as opposition forces threatened to take an important military airfield in Homa.

- “The Syrian regime has been under intense pressure. There’s a significant opposition offensive in Homa province, and connecting opposition lodgments in Homa province to Idlib province to the north is something that the opposition is trying to do. And they had significant pressure on the regime,” the official said. “So the regime was at risk of losing Homa Airfield, which is a significant airfield for them, where they fly rotary-wing helicopters out of there, it’s suspected to be a barrel bomb manufacturing facility, and so this was a significant risk to the regime. They were under a lot of pressure. We think this attack was linked to a battlefield desperation decision to stop the opposition from seizing those key regime elements.”

- On March 25, the Syrian regime dropped chlorine industrial chemicals on Homa.

- On March 30, the regime dropped an unconfirmed chemical on Homa, which a non-governmental organization on the ground said was consistent with a nerve agent.

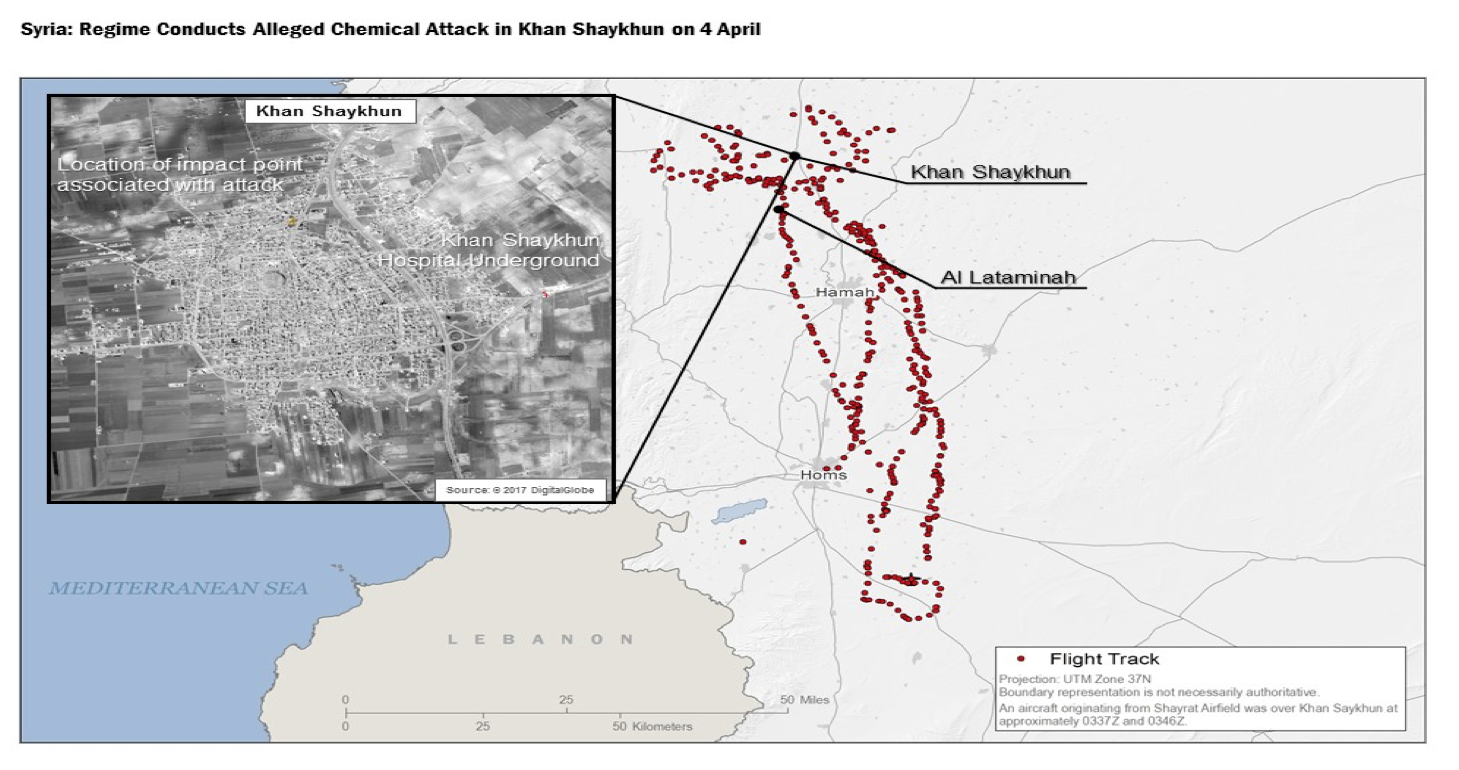

- On April 1, the regime dropped a sarin bomb on Khan Sheikhoun, in the in Idlib province, in the worst chemical weapon attack since 2013. The U.S. military has tracks of Syrian aircraft flying from al-Shayrat Airfield to Khan Sheikhoun and being in the area just before 7 a.m. that morning, around the same time that reports of sarin-related casualties started coming in.

- “We know the routes that the aircraft took, we know these aircraft were overhead at the time of the attack. The time of the attack was early morning, we suspect it was about 0650, 0655 or so. And reports of nerve agent-exposed casualties began almost immediately, at about 0700 we started to see the first reflections of a potential use of nerve agent,” the official said, adding it would “probably have been an SU-22” that dropped the chemical bomb – a Russian-built plane that the Syrian regime flies.

- “This escalatory pattern of using industrial chemicals, to using suspected chemical munitions, to verified chemical munitions caused us, obviously, great concern about the direction this was going and the risk to innocent civilians,” the official said. “We have high confidence that a nerve agent like sarin was used in Khan Sheikhoun; the symptoms are consistent with exposure to a nerve agent.”

- Shortly after the chemical attack, “as civilians began to flow into the hospital there in Khan Sheikhoun, a UAV (unmanned aerial vehicle) was seen over the target – a small UAV, either regime or Russian, flying over the hospital during the evacuation of the patients. There was lots of ambulance activity, and clearly people moving into a hospital. Some hours later, about five hours later, the UAV returned, and the hospital was struck with additional munitions (from a fixed-wing aircraft). We don’t know why, who struck that, we don’t have positive accountability yet, but the fact that somebody would strike the hospital, potentially to hide the evidence of a chemical attack … is a question that we’re very interested in,” the official said, noting that the plane that bombed the hospital was Russian built but it is unclear at this time if it was operated by the Russian or Syrian military, both of which use similar Russian fighters. The U.S. also has not identified who owned the UAV that collected intelligence for the hospital strike.

- The Russian government has tried to claim that opposition forces had a chemical facility in Khan Sheikhoun that was hit by a bomb, but the official pointed to evidence that the bomb hit – and left a massive crater – in the middle of a road, not near any buildings, as shown by multiple open-source video and satellite images of the town. The official said it was clear the bomb was dropped in a location near civilians and contained the sarin gas, and “any obfuscation of whether this was a nerve attack or not is really untenable in the face of the facts. … There’s no credible alternative to Syrian regime air attack as the source of the chemicals .. that killed so many Syrian civilians.”

- The U.S. military is now trying to determine the level of Russian complicity in the sarin gas attack. “We have a good picture of how the attack was executed. We know that the regime has a track record of using industrial chemicals, chemical-related attacks, and chemical capabilities, and I think we know they have the capability. We know they have that precedent. We know they have the expertise. And we suspect that they had help,” the official said. “We have a good sense of what happened and where it happened, we have a good sense for who executed the attack. We think we have a good picture of who supported them as well. Obviously, at a minimum, the Russians failed to rein in the Syrian regime activity, and again the continued killing of innocent Syrian civilians. We know the Russians have chemical expertise in country; we cannot talk about openly any complicity between the Russians and the Syrian regime in this case, but we’re carefully assessing any information that would implicate the Russians knew or assisted with the Syrian capability.”

- Beyond any potential ties to, knowledge of or support for the April 4 attack, the Russians in 2013 had offered themselves as the guarantor that Syria would turn over all its chemical weapons for destruction. The official said the U.S. had taken Russia at its word at the time that all chemical weapons had been removed, but in the aftermath of this attack U.S. intelligence will be paying close attention to sites previously used for chemical weapons attacks to look for further signs of current chemical weapons capabilities in Syria.