China’s compliance with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) tribunal’s ruling regarding rights, activities and entitlements in the South China Sea is much less certain than one might expect, we concluded in a previous post at Lawfare. By our analysis, there are no reports that China has taken actions in clear violation of nine of fifteen rulings handed down by the tribunal. Therefore, while China is not in “compliance” with the arbitral award, neither is it in complete “non-compliance.”

It is important, however, to more finely characterize the sources of our uncertainty, as they highlight different concerns about future Chinese behavior. We find three areas of uncertainty in China’s compliance with the award.

Ambiguous Claims to Historic Rights in the South China Sea

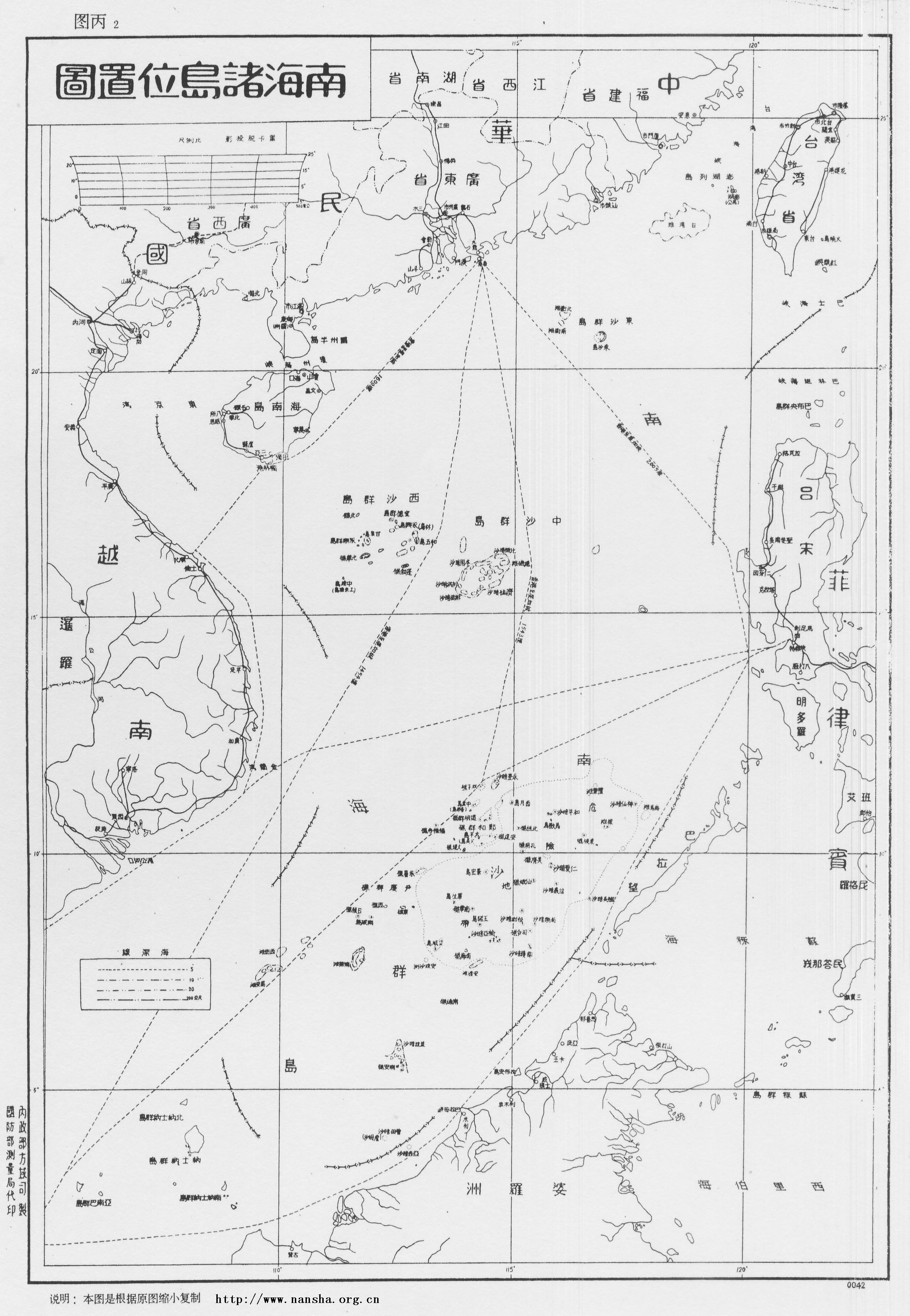

The tribunal found that UNCLOS superseded all historic rights not specifically provided for in the Convention. More specifically, it asserted that the only historic right available to China in its dispute with the Philippines would be traditional (artisanal) fishing rights within the Philippines’ territorial seas. Responding to the award, China reiterated that it has “historic rights in the South China Sea,” but never specified whether it agreed with the tribunal’s understanding of historic rights.

At first glance, this might seem like an area ripe for compromise. China could come away from a negotiation asserting that it had always understood historic rights to only include what was specifically provided in UNCLOS, appear to not capitulate to the Philippines, and extract concessions for scaling back its rhetoric. Years of nationalist propaganda, however, make such a grand bargain unlikely.

Chinese scholar Luo Xi, looking at populist responses to the ruling in July, found that modern populist nationalism “values national esteem more than [at] any time before.” Indeed, Luo reports that Chinese social media was flooded with army veterans pledging to “be back to the front” in the event of a war for the South China Sea. And while Beijing might temporarily benefit from this sentiment, nationalists may be getting ahead of the Communist Party. A week after the ruling was released, Chinese state-owned media began criticizing “irrational patriotism” as netizens boycotted foreign products (including IPhones and KFC) and “unpatriotic” movie stars.

If the Party’s narrative has indeed gotten ahead of its national interests, it is difficult to imagine how Chinese President Xi Jinping can redefine China’s historic claims under the 9 Dash Line to be limited to traditional fishing rights.

No Statements on Characterization of Specific Maritime Features

Much of the decision was spent assessing the legal characterization of disputed maritime features, including Scarborough Shoal, Mischief Reef, Subi Reef, and others. These characterizations matter. A feature that is above water only at low tide outside of a country’s territorial sea is not entitled to any maritime zone. A land mass that is above water at all times, but cannot sustain an economic life of its own or human habitation (rock) is entitled to a 12 nautical mile territorial sea. On the other hand, a land mass that can sustain an economic life of its own or human habitation (island) gets an additional 200 mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and entitlement to a continental shelf.

Faced with these stakes, China must grapple with two issues. First, it must determine whether it agrees with data used by the tribunal to characterize disputed features. There is relatively little contemporary data on the South China Sea’s geography and facts about the natural condition of some objects may never be known now that artificial islands have been built. But we do know that China is investing in technology to more accurately map and survey features in South China Sea, suggesting that, as its presence in the region grows, China will be better equipped to refute the tribunal’s factual conclusions.

China must also decide whether to accept the tribunal’s interpretation of “human habitation” and “economic life of its own,” UNCLOS’ ambiguous criteria for defining an island. The China-Philippines tribunal was the first to interpret these criteria, and it opted to construe them so as to “[prevent] encroachment on the international seabed” and “[avoid] the inequitable distribution of maritime spaces.” This narrow understanding likely runs contrary to many countries’ maritime claims and may explain why none have, as yet, taken a clear position on the tribunal’s analysis of this question. Given the stakes, it seems unlikely that China would move to do so first.

No Reports that China has Allowed its Vessels to Operate Unlawfully

Finally, the tribunal criticized operations by Chinese vessels that prevented Filipino nationals from fishing in the Philippines’ EEZ and posed a navigational risk to Filipino vessels. It also condemned China for failing to prevent its fishermen from exploiting endangered species, particularly giant clams. While there have been no reports since the decision was released that China has continued these activities, it certainly retains the capacity to do so. The biggest question going forward on these issues, therefore, is whether China will continue to refrain from this behavior.

We are most likely to see progress in negotiations arising from these issues because, unlike the above two categories, China is less restrained by domestic nationalism. It has greater latitude, therefore, to make concessions on these issues at the negotiating table. Something similar may be occurring right now as Beijing courts Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte by ratcheting down its plans for constructing artificial islands and engaging in other provocative gestures.

Takeaways

Ambiguity is not monolithic. In some areas, namely operations by Chinese-flagged vessels, it gives China leverage to improve its position at future negotiations and may open the door to a greater variety of solutions. In other areas, particularly regarding the precise nature of China’s 9-Dash-Line claims, ambiguity is less amenable to change and negotiation. It is highly unlikely we will see China publicly agree to comply with an arbitral award it has spent months denigrating and de legitimatizing. But that does not mean the actual terms of the arbitral award will not matter. Policymakers should remain attuned to this complex interplay of law, domestic politics, technology, and military power in assessing how the tribunal’s decision may be used as a basis for future negotiations.