ABOARD USS AMERICA — The new amphibious assault ship USS America (LHA-6) has raised more than a few questions in its short life, with sailors and Marines alike wondering what it will mean to have an amphibious ship without a well deck and therefore without the ability to deploy landing craft to move heavy tanks and equipment ashore.

America’s recent participation in the Rim of the Pacific 2016 international exercise may have allayed some concerns – the resounding feedback from those involved in the ship’s operations is that, if the Marines are willing to tweak the composition of the deploying Marine Expeditionary Unit (MEU), America can move them faster, more agilely and more safely.

“The idea is rapid mobility air assault. So the thinking with me and my Marines right now is, lighter companies, people that can move quickly via the (MV-22) Osprey and the (CH-53Es),” ship commanding officer Capt. Michael Baze told USNI News from his shipboard office last month.

The plus side to that concept is increased speed and safety for both the Marines and the ship’s crew, he said.

“I’m not looking to build a mountain of supply on the beach like the D-Day invasion, I’m looking to go straight to my objective from a great distance,” Baze explained.

“In terms of operations of the ship, I don’t have to worry about force protection for my ship as much because I don’t have to get two and three miles off the beach to deploy my Marines (on surface connectors). The truth is, I’m over 100 miles right now, we could deploy the Marines from here, I don’t have to get any closer. So in a world with mines on the shore, surface-to-surface missiles, these types of threats are always a concern, these are things that I think about. So it’s about mobility, speed, and when you look at operational maneuver from the sea and some of these concepts the Marines talk about, this ship really exemplifies it.”

The challenge, though, is for Marines to get “lighter.” Over the last decade and a half, the Marine Corps has tacked on more armor to its ground vehicles as protection from roadside bombs, and loaded up units and individuals with more weapons, more gadgets and more protection to succeed in ground wars in the Middle East. They have also grown accustomed to having heavy logistics gear – bulldozers, maintenance vehicles and more – on the ground to support long-term operations.

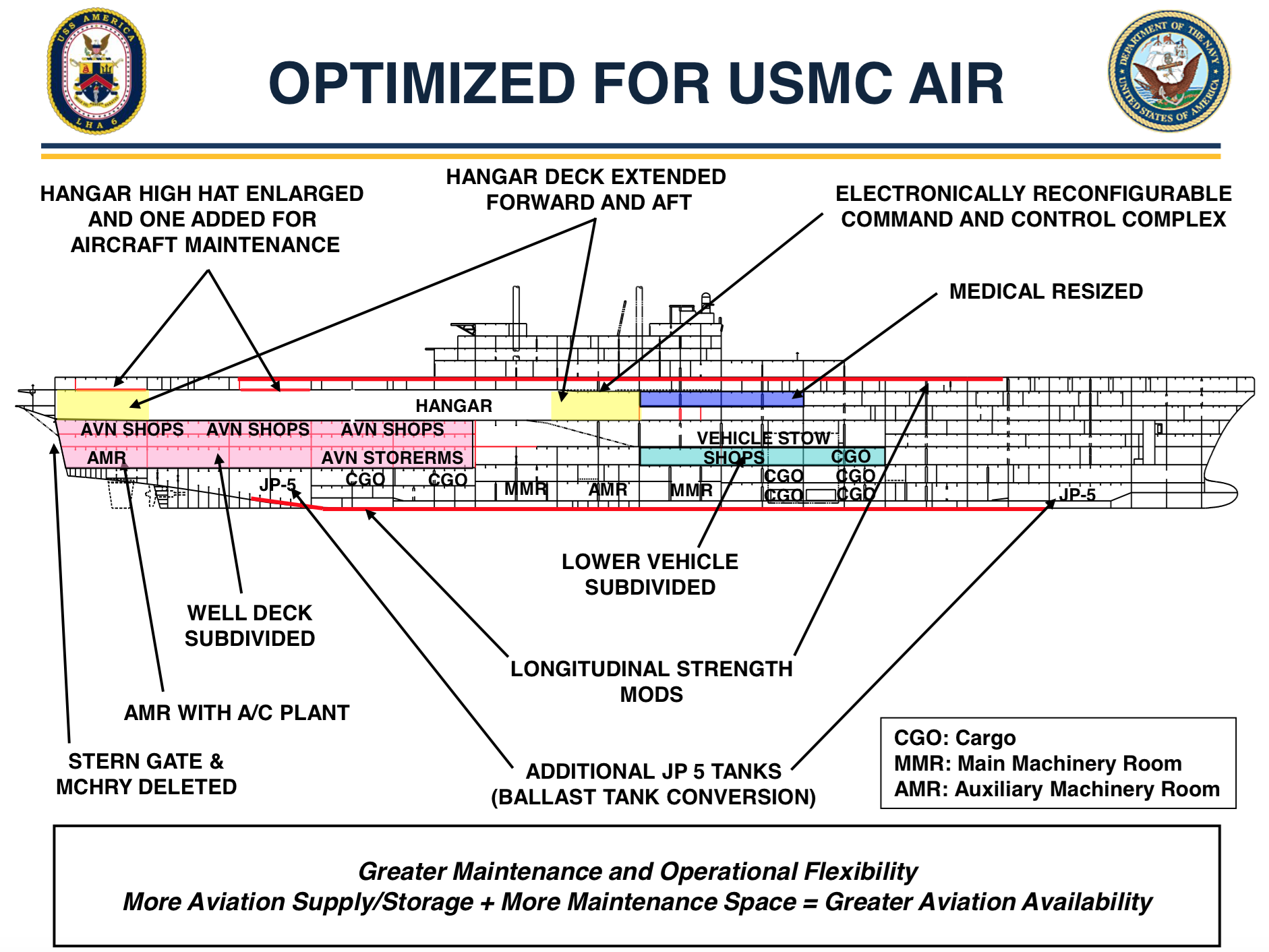

America was built to move a lot of people and cargo by helicopter very quickly, with enhanced maintenance facilities to support quick turnaround of aircraft and a 40-percent bigger hangar to store more and bigger aircraft.

“This ship’s about speed and maneuver,” Baze said, adding the ship is fulfilling that role very well. But it will never be a ship that moves tanks and heavy logistics trucks, which forces the Marines to decide if they want to load their heaviest gear on a smaller ship in the Amphibious Ready Group (ARG) or leave it at home.

The Navy will only build two LHAs without a well deck, inserting a smaller two-spot well deck into LHA-8 at the expense of some aviation and medical space. But with amphibious forces in high demand and the ship count still far below the Marines’ stated requirement of 38, the service’s ability to best leverage America will be important going forward.

USS America

The first-in-class America was designed with many improvements over its fellow big decks, Baze said. Primarily, it was built for the MEU of the future.

The ship has undergone modifications to support the F-35B Joint Strike Fighter, including flight deck strengthening to support vertical landings. Portions of the flight deck were paved with a special non-skid material designed to withstand the heat and wind of the MV-22’s nacelle that points down during takeoffs and landings – the non-skid is too expensive to use on the whole deck, but its use on America expands the number of spots on the flight deck the Osprey can use.

And its maintenance area was designed specifically for larger aircraft.

“The future Marine Air-Ground Task Force, the future MEU, is going to be designed around the Joint Strike Fighter, which has incredible capabilities but also takes up more space in the ship than the AV-8Bs; the MV-22s, which bring phenomenal capability but also take up more space in the ship than the frogs that they replaced,” Lt. Col. Eric Purcell, commanding officer of Marine Heavy Helicopter Squadron (HMH) 463 Reinforced and Aviation Combat Element commander for RIMPAC, told USNI News from the ship.

The hangar is 42 percent larger than a Wasp-class LHD’s hangar, the sealed-in well deck space was reconfigured as a much larger aircraft intermediate maintenance department work area, and the ship carries about four times more jet fuel than other big decks.

In addition to the aviation enhancements, the ship also has increased command and control capabilities compared to older LHAs and LHDs. America has large open architecture command and control spaces, at the request of the Marine Corps, and the new propulsion plant leaves plenty of open space in the engineering rooms that could host new systems in the future.

But, of course, the conversation always comes back to the well deck. Baze admits the well deck – and therefore the inability to use the fast Landing Craft Air Cushions and the heavy-lift Landing Craft Utilities – takes away from certain missions but said that “in the aggregate I would say it comes out as a wash.”

“What do I lose? I lose volume. So think about something like a humanitarian assistance/disaster relief mission. If I’ve got an area where people need help quickly, my ship is making 200,000 gallons of fresh water a day just sitting here. I can put that on the back of Ospreys. I can take flyaway capabilities – doctors, supplies – I can get those inland very quickly with Ospreys,” the skipper said.

“But, if I have to evacuate hundreds of people from somewhere, I could probably do that with one LCU or one LCAC; we could do that, but it would take us more time” with helicopters that can only carry a couple dozen passengers each.

America will have its first ARG/MEU deployment next year with USS San Diego (LPD-22) and USS Pearl Harbor (LSD-52) and the 15th MEU, and in the intervening year leadership will have to decide how to balance the rapid air mobility capabilities of the big deck with any potential operational need for heavier vehicles.

Changes for the Ground Combat Element

The crux of America’s operational concept is that if the Marines can lighten their MEU, this ship can move them ashore faster, going directly to their objective area instead of first stopping on the beach. The ship can project Marines ashore from a great distance from the beach, keeping the ship safe from land-based missile threats and keeping the Marines away from mines and other threats awaiting their beach landing.

While tailoring the MEU for this ship requires more planning upfront, the first battalion landing team commander to leverage America’s capabilities said his ship-to-shore movement during RIMPAC went well.

Lt. Col. Ryan Hoyle, commander of 2nd Battalion 3rd Marines, brought about 350 Marines ashore from America and 560 from San Diego in a landing during RIMPAC, which is the ship’s largest and most complex operational engagement since commissioning less than two years ago.

Moving the Marines ashore from America required flying two companies ashore by helicopter, whereas a typical MEU may only move one company by air. This could involve a slightly different training plan for the infantry companies so they can earn a heliborne certification, but Hoyle said the operational benefit was clear.

“For us, not having a well deck on the USS America actually allowed us to get the forces ashore a little bit quicker because we were able to do helo ops continuously off the USS America and do well deck operations (from San Diego) … without as much of a safety concern as you would have if you did both of those operations off the same platform,” he told USNI News from a training area on the island of Hawaii.

“Granted, command and control was more difficult because we were on two platforms, for me, but that’s going to be common because when a battalion normally goes out they’ll be spread across three amphibious ships.”

In the case of RIMPAC, all the amphibious ships were aggregated in the same area, working together to launch a single amphibious assault. However, that may not be the case in the real world, where high combatant commander demand for amphibious forces often leads to the LPD splitting off and working solo while the big-deck and the LSD stay together.

Knowing that, Marine Corps leadership and future MEU commanders will have to consider what gear to bring and how to spread it out on the ships, given that they could be conducting aggregated or disaggregated operations.

Marine Corps Chief Warrant Officer 4 Shane Duhe, America’s combat cargo officer, said Navy and Marine Corps leaders would have to be transparent with each other and with combatant commanders about which mission-essential tasks the America ARG would lose during split operations – amphibious beach assault potentially being the first one, since America would be left with just Pearl Harbor and its two LCACs. The COCOMs would have to decide for themselves whether to keep the ARG together to retain all mission-essential capabilities or peel off San Antonio to cover more annual objectives with partner nations.

Duhe said that, if the Marines choose to bring a traditional package of vehicles and weapons to meet mission-essential tasks, out of necessity the MEU would have to “really pack out the LPD-17-class ship to the gills” with vehicles that cannot be airlifted off America and their corresponding personnel: tank companies with the M1A1 Abrams tanks, Light Armored Reconnaissance companies and their Light Armored Vehicles, and the logistics combat element and its refueling trucks, maintenance trucks, bulldozers and other heavy equipment.

That frees up space on America to load the entire ACE on the ship instead of putting pieces of it on the LPD. Baze said his ship has room for the entire ACE with more room left over, giving future MEU commanders flexibility to bring a bigger ACE or to change up the mix of aircraft.

But it’s still unclear what that stark separation – the heavy ground equipment only on the LPD and the ACE entirely on the big-deck – would mean for split-ARG operations.

Alternatively, Duhe said, the MEU could leave some of this heavy ground equipment behind and “change the way that they make decisions about what to take and still accomplish those mission-essential tasks.” If it takes one LCAC to move a single tank ashore, and the entire ARG only has four LCACs total, the MEU may look for alternate ways to meet mission requirements without tanks, for example.

Several officers emphasized the need to lighten the ground combat element attached to the America ARG. Capt. Homer Denius, commodore of the Amphibious Squadron 3 that will lead the America ARG on deployment next year, made clear that “that idea of a lighter MEU is going to have to come into concept” ahead of the deployment. The balance is that a lighter maneuver element means America can support a larger maneuver element – and striking that balance was part of the success during RIMPAC. When ground troops moved ashore, the largest vehicle they brought with them was Australian LAVs. Baze said America pushed out a company of Marines on a couple CH-53Es from 50 miles offshore “before lunchtime,” with the simplicity of moving a lighter company showcasing what America was built to do.

The follow-on CH-53K, set for fielding at the end of the decade, will only make this easier. Purcell said the next-generation heavy-lift helo will externally carry 27,000 pounds of cargo 110 nautical miles from the ship at 3,000 feet elevation, making it “a key connector for America” in lieu of surface connectors.

“When the 53K is onboard, Humvees and all these things that would have normally been brought ashore by surface connectors can be brought not only from the ship to the shore but from the ship to the objective area, which is going to be a critical combat enabler for the Ground Combat Element to know that they don’t have to just establish a beachhead – we can bring their Humvees, we can bring their artillery tubes, we can bring all their principle end items to a place of their choosing vice where the LCUs can get to or where the LCACs can get to,” Purcell said.

“And that’s something that I think a lot of people don’t understand and they overlook when they talk about the America or what some of the tradeoffs are.”

A Command and Control Ship

While much of the discussion around America has been focused on taking a new ship design and forcing a traditional mission on it – that of a ARG/MEU flagship – Duhe suggested the ship is actually better suited for a Marine Expeditionary Brigade-level operation.

The MEB is the Marine Corps’ “middle-weight” fighting force, which could be as small as two ARG/MEUs or as big as five, depending on the circumstances around its organization.

Duhe argued America has several key features that lend itself to being the flagship of a MEB. The command and control rooms are spacious and modular, with the ability to bring new systems in and plug into the open architecture set-up to communicate with other ships in the Navy, with forces already on the ground, and with international partners as needed. The hangar is large enough to allow for flexibility in the size and composition of the ACE – or to accommodate other ships’ aircraft as they ferry in leadership as needed for planning. And the ship can stay on station much longer than its counterparts before having to meet a supply ship for refueling at sea – it holds 1.3 million gallons of jet fuel compared to 300,000 or 400,000 gallons on other amphibs, and the ship’s gas turbine engines for primary power and diesel engines for sailing at lower speeds mean the ship may consume as little as half the fuel other big decks would use.

“Ultimately this ship is a wonderful ship to support MEB operations, especially from a command and control perspective,” Duhe said.

“I don’t personally believe this will remain in a traditional MEU role, nor do I believe that’s really what she was built for and really designed for, so there’s a future for the ship that’s still coming about. … It still has a story to be told.”

The last time the Marine Corps used a MEB for combat operations was Task Force Tarawa for the 2003 invasion of Iraq, Duhe said, and he noted that the amount of time, money and resources it takes to compile a MEB makes it cost-prohibitive to train for such a massive operation in live exercises. But post-Iraq and Afghanistan, the service has been focused on MEB-level command and control rather than MEU-level C2, he said, which could be to the benefit of America and its sister ship, the future Tripoli (LHA-7).

“Everything that we’re doing with our Marines from Hawaii (during RIMPAC), it’s with that higher-level mindset,” he said, with RIMPAC using a MEB-level leadership team but a MEU-sized live force.

“You can’t do that in real live training, it’s too much money and resources, but to have the command and control in place, to stay in the MEB-level mindset and have leadership be in big deck vessels like this, (working on) interoperability with the Navy at sea, that’s very important to the Marine Corps.”

Duhe’s notion of America serving as a MEB flagship harkens back to the previous class of amphibs without a well deck: the LPHs built in the 1960s. They were operated at the MEU level but led a five-ship ARG, obviating any disadvantage caused by not carrying surface connectors of its own. Operating America and Tripoli as MEB flagships would have a similar effect.

Benefits for Marine Aviation

If America raises questions about how the ground community will use the ship, it provides endless opportunity for the aviation combat element to experiment with how to best leverage the aviation-centric design.

Purcell said the design – and in particular, two hangar high-hat areas for aircraft maintenance – “has given us a number of opportunities that we wouldn’t have had otherwise.”

While America was sailing to Hawaii for RIMPAC, one of the Ospreys needed maintenance that required putting the aircraft on a jack and working on it with the wings fully spread.

“On an LHA, the original LHAs, that wouldn’t have been possible. And I don’t think it would have been possible on the LHD because we did have to have the rotors in the up position for the work we were doing,” and the older ships do not have enough space inside the hangar to work on the Ospreys while fully spread out. On the older ships, therefore, the work would have to be done on the flight deck, which could interrupt flight deck operations and slow down sorties during combat operations.

Purcell said the same is true for changing the main rotorblade on the CH-53E – given the clamps and cranes needed for the job, it can only be done inside America thanks to the two high-hat areas in the hangar. The bigger hangars were designed not only for the height of the Ospreys and heavy-lift helos but also for the greater footprint of the Joint Strike Fighter, which will come onboard in the next few years.

Lt. j.g. Nick Haan, assistant maintenance officer for the Aviation Intermediate Maintenance Department, said the ship was not only designed for bigger aircraft, but also for more aircraft.

“AIMD is where the well deck used to be. They laid it out in a way that would flow almost like a carrier, so the whole second deck where the well deck used to be is all AIMD now,” he said after touring USNI News around the I-level maintenance area.

“So we can get components up and down via elevators, weapons elevators, and we can actually perform the maintenance right here without having to jump around, crane things up and down to different decks or have people work on it in the hangar. We can get it to where the actual tools are.”

The AIMD has the same capabilities as on other LHAs and LHDs – it has a structural shop to repair damaged metal components, a non-destructive inspection shop to test the integrity of aircraft and support equipment, a calibration lab to ensure the accuracy of all the tools, and much more – but on a greater scale and arranged to promote a more efficient turnaround for an aviation-centric MEU.

Baze touted the AIMD as a key enabler, saying “all this equates to faster sorties, faster movement of troops.”

“I can’t prove it to you until we do a deployment, but I guarantee you that’s going to translate to faster, more efficient movement of parts and machines to fix the aircraft,” he said.

Overall, Brig. Gen. Raymond Descheneaux, commanding general of Fleet Marine Forces in RIMPAC 2016, said the services are still sorting through what exactly America’s first deployment with the 15th MEU next year will look like, but he’s confident the new ship will find its niche.

“We’ll only have LHA-6 and LHA-7 before we go back to the well deck, so my conversation with the ship’s captain is, hey, you have an opportunity to capture best practices, and the 15th MEU who will actually be sailing on her soon will have an opportunity to figure out how we task organize to exploit those capabilities,” he said on the Hawaii training range during RIMPAC.

“And what this becomes is just another tool in the tool chest. San Diego still carries the full complement of AAVs and two LCACs. So what we’ve had to do is just slightly shift our load-outs, but at the end of the day restructuring that amphibious capability to allow us to bring additional over-the-horizon (capability) from an F-35 and V-22 will truly become a game-changer, and America’s on the front-end of that.

“How that’s going to be employed, what shortfalls we see as we’re [building] the best structure for this, is truly going to have to get filtered out, will get filtered out, they’ve already gotten a great start,” Descheneaux continued.

“But at the end of the day, when America was built there were a lot of people scratching their heads. … Now, by every account I get from America, there’s incredible goodness. And I think once we start populating that platform with the F-35 it will only grow exponentially. And then to have (LHA) 6 and 7 with that capability when we need to have power projection down the road will be just again another more specific tool in our arsenal, a tool in the chest to meet our nation’s intent.”