ABOARD USS AMERICA, NEAR HAWAII – As the head of the Rim of the Pacific 2016 amphibious task force progresses through the exercise, the New Zealander works from an office aboard an American ship filled with Australians, Indonesians and other personnel from the across the Pacific.

And for Commodore James Gilmour, that’s just how Pacific operations should be.

RIMPAC 2016 features a blended international force, from the leadership staff down to individual platoons. The ultimate goal of the exercise – underscored by its motto, “Capable, Adaptive, Partners” – is to form relationships that will outlast this event and benefit future international exercises and real-world operations, he said.

“We’re aware – particular a country the size of New Zealand and an armed forces the size of New Zealand – that almost nothing from a security perspective, meeting our responsibilities from a security perspective, will be dealt with on our own,” said Gilmour, New Zealand’s Maritime Component Commander and RIMPAC’s Commander of Task Force 176.

“So therefore, being adaptive and interoperable with other nations, our partner nations, is essential. And we endeavor to do that kind of training often with our regional neighbors, including the United States, and the opportunity now to be part of RIMPAC in a command position is not only a great honor but its’ a great opportunity and it allows us to prove that our training is aligned and of a similar quality.”

The exercise revolves around a notional adversary – but one that mimics real concerns around the globe. In the scenario, “Orion” is “what we would call a recalcitrant state, a state that is not necessarily getting on well with its neighbors, has a desire to expand, has a desire to secure resources that are not necessarily within their territories. And that scenario is something that I think is realistic,” Gilmour told USNI News aboard the expeditionary strike group’s flagship USS America (LHA-6).

In the scenario, an insurgent group in the nearby coalition country of Griffon is also challenging the coalition, forcing actions all along the range of military operations to deal with enemy states and non-state actors. If this scenario were to play out in real life, no single country would take on the challenge alone, RIMPAC leaders stressed.

“We recognize the Pacific region is far too large and far too complex for any one nation,” Brig. Gen. Raymond Descheneaux, commanding general of Fleet Marine Forces in RIMPAC 2016, told USNI News from a training area on the island of Hawaii.

“We don’t care how many toys you bring to the game. We don’t care how much money or how much influence your nation has. When you come here, we are all a team, and as a team we are going to train and we are going to learn from one another.”

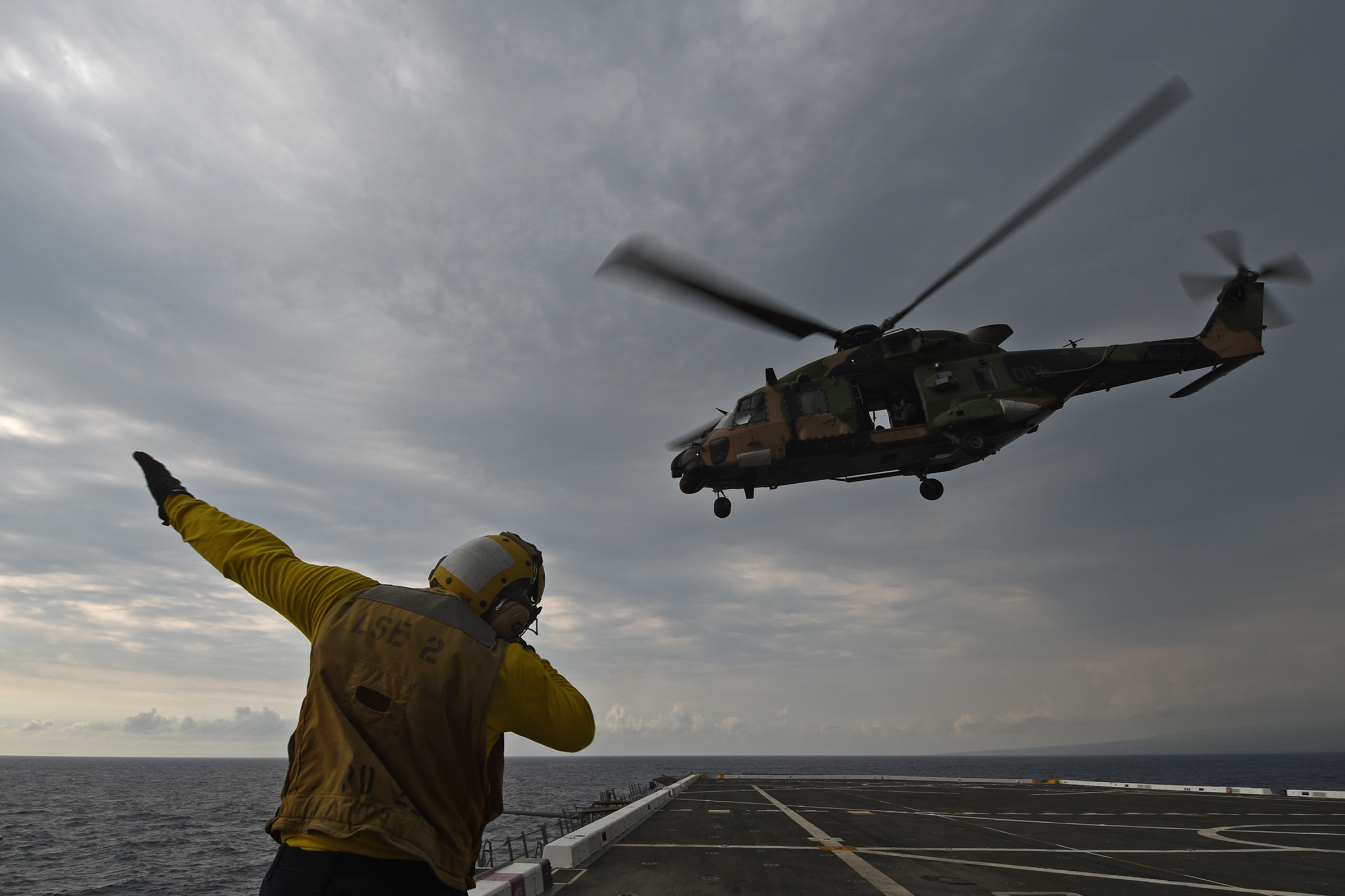

Gilmour described the process of assembling a coalition force to deal with a threat of this nature: leadership would come together and make sure they were speaking the same language and working towards achieving the same outcomes. The forces would physically come together to ensure they could operate with one another – helicopters and ship-to-shore connectors landing in and on foreign ships, land forces going ashore in foreign aircraft, and supporting ships and submarines providing adequate protection in all domains for the forces going ashore.

While that may sound easy to some, the international coalition faced some very real challenges.

Lt. Col. Eric Purcell, commanding officer of Marine Heavy Helicopter Squadron (HMH) 463 reinforced and the aviation combat element (ACE) commander for RIMPAC, told USNI News in an interview aboard America that he has worked with many of the RIMPAC 2016 partner nations in previous assignments.

“A lot of the forces we’re seeing here are forces we’ve operated with in the past. That being said, they’re not used to CH-53s, they’re not used to V-22s,” he said, due to the smaller scope of some bilateral exercises and the newness of some of the U.S. and partner planes and ships being used in RIMPAC 2016. As a result, “all the standard things – making sure they can get in and out of the aircraft efficiently, effectively and safely, this is a great exercise for it.”

“We view RIMPAC as a mission rehearsal exercise – if we have to go to war in the Pacific, these countries are likely going to be our allies and we’re going to likely work with them, so I think it’s important that we build those relationships that will bear fruit in the future,” Purcell continued.

“Even if it’s not war, if it’s anything on the spectrum of operations – quite honestly, humanitarian assistance and disaster relief operations are not uncommon in the Pacific, and building these relationships now will pay dividends in the future.”

Among the many firsts of the exercise, a U.S. Marine Corps MV-22 Osprey landed on the deck of the new Australian amphibious warship HMAS Canberra (L02) for the first time. U.S. Marines also put amphibious assault vehicles on Canberra and the Mexican ship ARM Usumacinta (A-412), Descheneaux said.

“The fact that now we have validated processes that we believed were all legit and now have been sanctioned, the thumbs up, said yes we can do that – so the next tsunami, the next earthquake, the next typhoon, the next fill in the blank, regardless of what the situation is, those habitual relationships will allow us to come together that much more efficiently and step forward to fight our fight, whatever it may be.”

This high-end mission rehearsal is not just helpful for foreign partners learning to work together but also for the U.S. military, Purcell noted. His squadron and others based in Hawaii only go to sea every other year for RIMPAC, and “when historically you only get on a ship every two years, we’re focused on safety, security, accountability, making sure we can do everything that we’re tasked in a safe and effective manner,” he said. Even getting email and phones set up was a bit of a challenge for the Marines not accustomed to working aboard a ship, so the exercise was truly a learning experience for all involved, he said.

Aside from the physical interoperability of the ships and aircraft, Gilmour said there was a certain amount of cultural interoperability that needs to be developed early on in an exercise like this.

Talking about Commodore Malcolm Wise, the Commodore Warfare of the Royal Australian Navy, Gilmour joked that “the way the Combined Forces Maritime Component Commander might ask, ‘is everyone well and is everything serviceable,’ he would say, ‘are you in good nick?’ And of course being a New Zealander, we’re only 1,200 nautical miles away, I was able to understand what he was saying, but not many other people did. And to prove that we were getting to a place where we were speaking a similar language – even if it was Australian – my U.S. Marine Corps commander of land forces Col. Ward Cooper was able to say to me, ‘tickety-boo’ as a response to ‘are we in good nick.’ I would never expect that anywhere outside of Australia that anyone would understand that the correct Australian response to ‘are you in good nick’ is ‘we are tickety-boo,’ but Ward Cooper understood that that was the right answer.”

The emphasis on relationships and interoperability of all kinds is evident in the schedule of events. The initial harbor phase in Hawaii consisted of basic interoperability drills by day – combat-ready troops practicing getting on and off foreign countries’ helicopters, ensuring communications systems can talk to one another – and cultural education events by evening. Then, recognizing the realities of life in the Pacific, the first drill simulates a natural disaster and asks a multinational coalition to come together for a humanitarian assistance mission.

Next, a force integration phase works on individual and unit skills, as well as putting aircraft and connectors on foreign ships and testing command and control of large multinational forces. Finally, the free-play phase tests these newly honed skills, with the simulated adversaries acting and reacting to coalition operations.

Rear Adm. Dan Fillion, the U.S. Navy’s Expeditionary Strike Group 3 commander and RIMPAC’s deputy commander of Task Force 176, told USNI News aboard America that the international forces have so far proven to be “superb” and primarily differ in their size and capacity. That the highly trained military force first rehearses a disaster relief scenario during RIMPAC “sends a tremendous message writ large to the world that this is a formidable force, individually and then joined together, and the first thing we can do very very well for anybody in the coalition or the world is to go provide relief.”

Fillion oversaw the amphibious exercise Dawn Blitz 15 last fall, which involved three partner nations sending military forces and three more participating on a staff level, and he said that experience provided a lot of lessons learned that helped get RIMPAC 16 off to a smooth start.

“As soon as we got done with Dawn Blitz 15, our after action report … was transmitted to the initial planning conference for RIMPAC 16,” he said.

“On command and control, we had some challenges in Dawn Blitz 15. … We have not had similar problems here because we saw what they were and were able to eliminate them from the start.”

He said he also had a good understanding of some partners’ capabilities from Dawn Blitz, so when those militaries volunteered to take on certain missions in RIMPAC he knew exactly how capable that force was for that mission.

The exercise itself also evolved based on feedback from the 2014 participating forces – including an opinion among the ground forces that there was a shortfall of close-air support. Descheneaux said this year’s Fleet Marine Forces side of the exercise has more than 50 aircraft specifically supporting the Marines and soldiers coming off five amphibious ships. The “robust” CAS capability to support troops on the ground appears to be helping each country better meet their training objectives, which are submitted ahead of RIMPAC and tracked throughout to ensure each country gets what they need out of the exercise.

Descheneaux said he could see the exercise continuing to grow in the future, with an even greater emphasis on the humanitarian assistance/disaster relief piece, which garnered a lot of interest this year. RIMPAC organizers added the Southern California piece for the first time this year, and he said he thought the exercise may continue to find ways to grow going forward.

“My take is, the senior leadership is all for being inclusive, but we don’t want to dilute the quality of the training that’s taking place now,” he said.

As the exercise evolves and grows, Fillion said the emphasis on international cooperation – with countries operating side by side from the platoon level all the way up to the three-star task force commander’s staff – will remain.

“Often times we come into situations and, okay, we want to be in charge. We’re clearly not in charge, and that’s a good thing, we don’t need to be,” Fillion said of the American role in RIMPAC.

“Us not being in charge is allowing us to learn some things that normally we wouldn’t be. That has benefitted the entire force greatly. Working with coalition partners, we see we think a lot alike – and there’s instances where we don’t, and that has made us better.”