The long-awaited tribunal ruling on China’s territory grab of the Western Philippine Sea finally emerged on July 12. As expected it was a mostly clean sweep for the Philippines government—judging that the claims under the PRC’s Nine-Dash Line vision were invalid, and its current activities of island reclaiming and resource grabbing were both illegal and harmful to the environment.

However, the hard part has just begun. For the two years that the case slowly made its way through the court, China repeatedly stated that the court had no jurisdiction, and in no way would Beijing recognize the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s decision.

So where does that leave Manila now?

It’s been a storm of uncertainty for the embattled Philippines. The tribunal’s decision came right on the heels of Rodrigo Duterte’s presidential inauguration. The new leader is arguably a wild card for the how the United States and other claimants will handle the regional disputes.

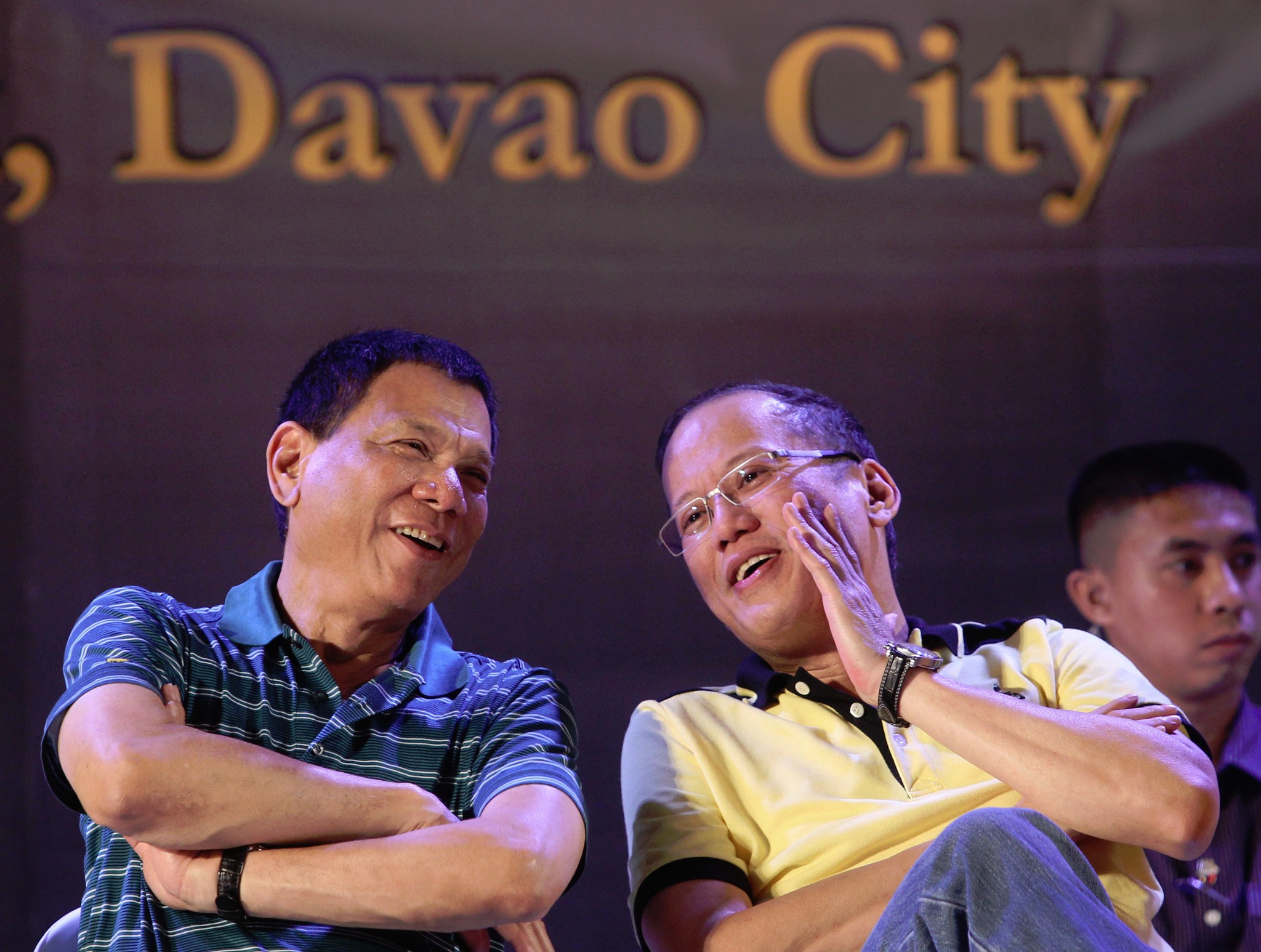

Duterte is a study in contrasts compared with his predecessor, Benigno Aquino III. The Aquino administration was marked in large part by a return to closer ties with the U.S., as the Philippines reeled under the pressure of China’s intrusive expansion in the region’s maritime space. Aquino recognized the weak state of the Philippine military, and chose to accelerate the modernization process while taking the fight to China. Simultaneously his administration opened the way for American forces to return to the Philippines through the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA).

As the hard-charging, tough-talking mayor of Davao City, Duterte rode to power on a plurality vote. Known for his brusque, no-nonsense—at times crude—personality, Rodrigo Duterte views the United States with a certain level of hostility. He has at times considered the Philippines as simply a pawn between great powers, in a game that he would rather see the nation exit cleanly and quickly.

While he has carved a reputation as an effective small-government leader, Duterte has little experience in dealing with foreign policy at a national level. His choice of Perfecto Yasay as foreign affairs secretary, a noted businessman with no foreign service qualifications and a controversial former chairman of the Philippines Securities and Exchange Commission, has already resulted in policy statement bungles that may have weakened the Philippines’ position following the tribunal’s decision. While it’s unclear who solicited whom, Duterte was briefed on the complexity of the decision by three prominent members of the Philippines legal team that presented the case—including Supreme Court Judge Antonio Carpio, arguably the foremost knowledgeable expert on the case.

It is unknown what, if any, recommendations emerged from either of those sessions. But the muted response from Malacanang Palace immediately following the tribunal decision is likely a reflection of several factors.

First, the Philippines remain weak in terms of kinetic responses to China’s incursions. While the Aquino administration consistently refused to “rock the boat” and make provocative moves that it felt might negatively influence the PCA’s decision process, both presidents are held hostage by the poor material and qualitative state of the Philippines military. Despite a modernization effort that outspent several previous administrations put together, the acquisitions made under Aquino barely put a dent in the so-called “death spiral” effect of the Philippines armed forces that started just after the evacuation of U.S. forces in the wake of Mount Pinatubo’s eruption.

Any confrontational action by the Philippines would have to leverage the country’s poorly equipped Coast Guard to mitigate clashes leading to general war with China. The branch lacks sufficient hulls to establish presence operations, and the boost of Japanese-made patrol boats comes too little, too late to make a difference. The loss of Scarborough Shoal, which indirectly led to the filing in the court, is once again a flashpoint. Located in what the PCA has determined to be the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone (EEZ), the Chinese Maritime Agency continues to deny Filipino fishermen access to the grounds. Judging by the recommendations of local government units for those affectded to find other means of living, it’s clear that a there is little appetite or capability to impose a kinetic solution.

While Foreign Secretary Yasay’s latest negotiations reflect a more assertive approach that leverages the PCA decision, Duterte is quite simply in a bind. China is one of the Philippines’ largest trading partners, and the prolonged conflict over territorial sovereignty has affected economic ties—everything from bananas and mangos to tourism. The newly installed president has even openly mulled the idea to trade concessions on the Spratlys in return for a Chinese-made transportation system. Only a strong Cabinet and trusted subject-matter counsel can guide Duterte at this point through these unfamiliar waters.

Duterte’s campaign promises to resolve a perceived national drug problem and bring peace to a war-torn insurgent-laden Southern Philippines is also competing with foreign policy objectives for resources. The controversy around extra-judicial killings and rampant corruption aside, the armed forces of the Philippines will have to use its meager resources to supplement, and in many cases, perform basic law enforcement actions that the even more destitute Philippine National Police cannot execute. By populating his Cabinet with prominent leftist and insurgency-aligned political figures, Duterte is calculating that he can co-opt most of the remaining rebel movements in the troubled southern end of the nation. However, he has also directed incoming Secretary of National Defense Delfin Lorenzana to realign the armed forces modernization back to counterinsurgency operations as needed in order to strike what is hoped would be a fatal blow to hard-line terror groups such as Abu Sayaaf. Given the challenges that already plague the military’s upgrade efforts, this immensely sets back a credible external defense and further limits kinetic options to enforce the PCA ruling.

While on the campaign trail, Duterte indicated he would consider letting the enhanced defense cooperation agreement (EDCA) with the United States stay in place, acknowledging that the U.S. presence mitigated the Philippine’s weak defense status. Given that cold marriage of convenience however, it’s entirely possible that a diplomatic solution with China over the Spratlys might require the Philippines to severely curtail or even sever the burgeoning U.S. military presence. After all, EDCA was established via executive order, and could easily be reversed using the same power.

Such a move would be a blow to the U.S. pivot to Asia, as well as a reputational win for China. If America’s most erstwhile figurehead ally in the maritime dispute could turn to Beijing, it would seriously undermine the confidence of other regional claimants in putting stock with Washington.

Despite the cheers heard around the globe following the court decision, no other nations have really stepped forward to change the equation with regard to accessing the Spratlys or mitigating the Chinese presence. For all intents and purposes, the Philippines continues to stand alone despite its legal victory. The courses of actions are scant if any, and freedom to maneuver severely curtailed.