Is China about to declare an Air-Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) over the South China Sea? And how effectively would it be able to enforce such a zone?

The idea that China would declare a South China Sea ADIZ is not new, having been around since China declared one over part of the East China Sea in 2013. However, the very unfavourable ruling by the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea Permanent Court of Arbitration on overlapping claims between China and the Philippines in the South China Sea that invalidated most of China’s claims have again stoked worries that China will now declare one in retaliation, with Chinese Vice Foreign Minister Liu Zhenmin saying such a move could be an option if Beijing felt threatened.

That then leads to the question of how effectively China will be able to police a new ADIZ. It has been reported that China has quietly stopped seeking to actively enforce the East China Sea ADIZ, with a March 2016 report by the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission suggesting that a lack of coordination between China’s People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) and People’s Liberation Army Navy – Air Force (PLANAF) has led to radar coverage gaps and an inability to effectively police the ADIZ.

China has taken steps to remediate the coordination issue, however, with the reported formation of a Joint Operations Command Center for the East China Sea in early 2015. Moreover, the issue of PLAAF-PLANAF coordination is less likely to arise for a South China Sea ADIZ, with the entire region primarily coming under the jurisdiction of the PLAN’s South Sea Fleet (SSF).

In addition to its naval vessels, the SSF also has two PLANAF Naval Aviation Divisions under its command. Like the rest of the PLA, the PLANAF has undergone a drastic modernization starting from the middle of the past decade, and the SSF’s 8th and 9th Aviation Divisions having swapped their elderly J-6, J-7 and J-8 fighters for the newer and more capable Xi’an JH-7A fighter-bomber and Shenyang J-11B fighter.

Both of the SSF’s aviation divisions are made up of three naval aviation regiments, which in the case of the South Sea Fleet, comprises two combat regiments of approximately 24 aircraft per regiment based on Hainan island, at the northern end of the South China Sea. If China were to declare a South China Sea ADIZ, the responsibility to patrol and enforce the ADIZ is almost certain to fall primarily on the shoulders of those four regiments.

Xi’an JH-7

The JH-7 is a twin-seat, twin engine design that entered service with the PLA in the 1990s. Designed primarily as a maritime strike platform armed primarily with the YJ-82 anti-ship missile and free-fall bombs, the first examples used the Rolls-Royce Spey turbofan engines imported from the United Kingdom. Later examples used a license-built copy known as the Xi’an WS-9.

The Chinese introduced an improved variant designated the JH-7A into service in 2004, adding precision strike capability to the type with a new generation of guided bombs and targeting pods. Both the JH-7 and JH-7A are fitted with indigenous multimode radars and have limited air-to-air capability, but the type is perfectly capable of ADIZ enforcement. This was demonstrated on 15 September 2015, when the Pentagon said a JH-7 carried out an unsafe intercept of a U.S. Air Force RC-135 over the Yellow Sea.

The SSF’s 9th Aviation Division, 27th Aviation Regiment currently operates JH-7As at Ledong in south-western Hainan. The unit’s aircraft took part in the Haiyang Shiyou 981 standoff against Vietnam in 2014, most likely providing reconnaissance and overwatch against Vietnamese attempts to reach an oil rig then operating in waters disputed by both countries.

The base at Ledong has also been substantially hardened over the past decade and a half, with satellite photos from 2002 showing construction of an underground aircraft storage facility tunnelled into a nearby mountain. Subsequent satellite imagery showed that this was operational some time prior to 2008.

Shenyang J-11B

The SSF’s three remaining air combat regiments operate the Shenyang J-11B Flanker. The J-11B is an unlicensed Chinese-built version of the Sukhoi Su-27 using Chinese avionics, and beginning from around 2010, the Liming WS-10 Taihang engine. China acquired 76 Su-27SK/UBKs delivered between 1991 and 2009, in addition to building around 100 examples under licence known as the J-11A.

Development of the J-11B began as early as 2002, with the Chinese keen to incorporate various indigenous modifications and upgrades to the airframe with improved manufacturing methods as well as Chinese radar, avionics suites and weaponry such as the PL-8 and PL-12 air-to-air missiles.

It was also hoped to include the more powerful WS-10 into suite of local modifications, but well-documented issues with the WS-10 and China’s indigenous engine program derailed that, and the initial batches of J-11Bs were built instead with the Russian AL-31 engines that power the Su-27.

From 2010, a navalized version of the J-11B, known as the J-11BH, was put into service with PLANAF aviation regiments. The first PLAN regiment to convert the new type was be the 8th Naval Aviation Division’s 22nd Regiment at Jialaishi in northern Hainan, with photos of J-11BHs and twin-seat J-11BSHs appearing around the 2012 timeframe. The 22nd Aviation Regiment was the unit involved in the controversial intercept of a U.S. Navy P-8A Poseidon multi-mission aircraft off Hainan in August 2014, where it was reported that the J-11 performed a barrel roll over the P-8.

The 24th Aviation Regiment is the 8th Naval Aviation Division’s other air combat regiment, also reported to be based at Jialaishi. The regiment turned in its obsolete J-7EHs (improved Chinese-built MiG-21 Fishbeds) for J-11BH/BSHs around 2013-2014, about the same time as the last Hainan-based PLANAF combat regiment.

This was the Lingshui-based 9th Naval Aviation Division’s 25th Regiment, which previously operated the J-8 Finback interceptor, and whose claim to fame is being the unit involved in the collision with a U.S. Navy EP-3E Aries II Signals Intelligence (SIGINT) gathering aircraft in 2001 which resulted in the damaged EP-3 force-landing at Lingshui and the loss of one of the PLAN’s J-8s and its pilot.

Lingshui is currently undergoing refurbishment that began sometime in late 2014 or early 2015, with satellite photos indicating that at the very least, would involve the lengthening of the runway, expansion of apron space and the construction of weather shelters for based aircraft. The work also includes substantial land clearing around the base, which could point to the possibility that a network of hardened aircraft shelters may eventually be built on site.

The J-11B would be a formidable asset with which to patrol and enforce a South China Sea ADIZ. Capable of carrying up to 10 air-to-air missiles and with an internal fuel capacity of almost 10 tons, it is almost an ideal platform for a mission that requires a fighter with the persistence and endurance to undertake long missions far from home.

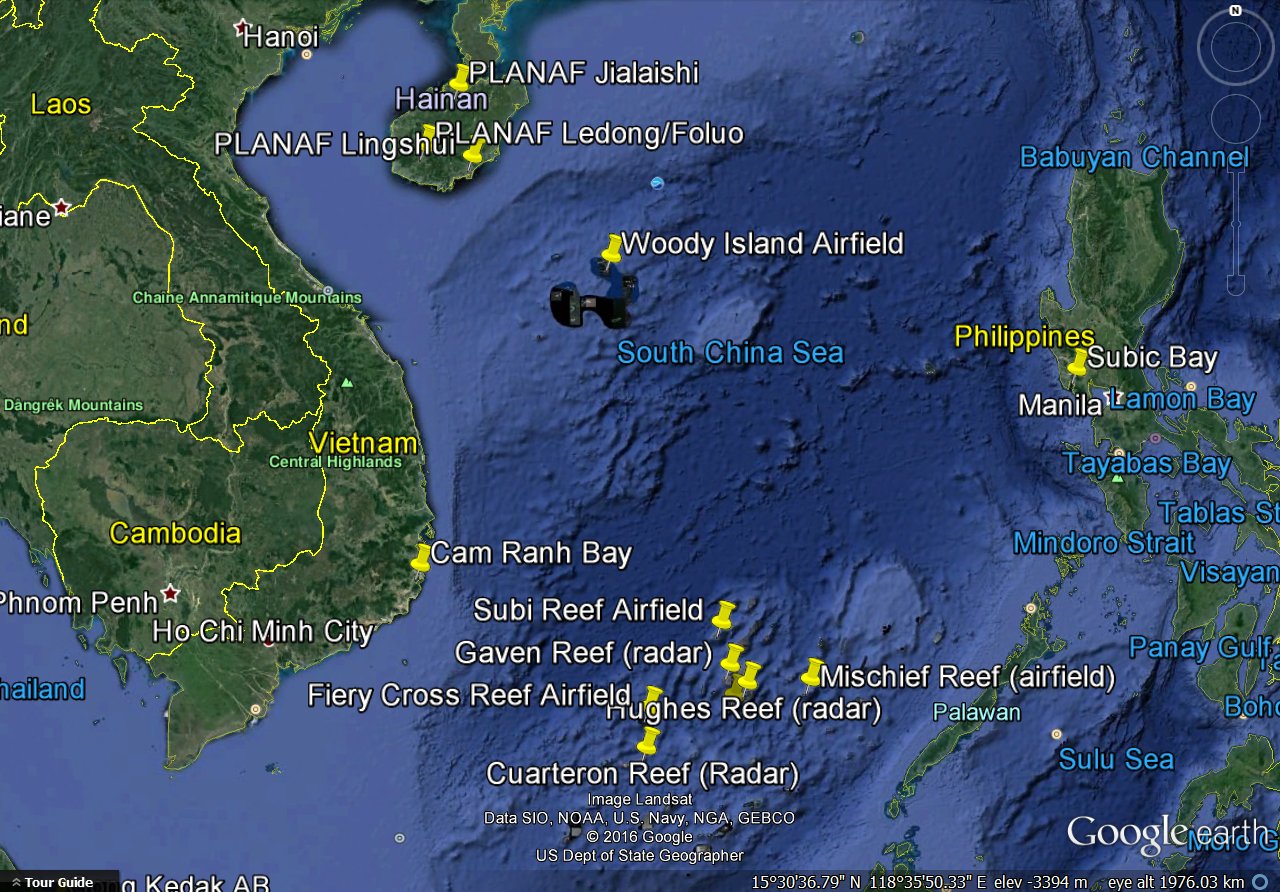

The PLANAF has deployed its Hainan-based J-11s to the airport at Woody Island in the Paracels, and it is not unthinkable that they will eventually regularly operate from there as well as the reclaimed airfields on Fiery Cross, Subi or Mischief Reefs, providing the PLAN with the ability to deny access to the region.

Early Warning network

China’s massive and controversial land-reclamation and construction program has included the construction of radar facilities at most disputed South China Sea locations on which it has built. As the accompanying map shows, the radars are located a long way away from China, with the Cuarteron Reef radar facility, which is believed to contain both high-frequency air search and regular multi-mode radars, located approximately 675 miles from Hainan. When fully operational, those radars are expected to provide an air picture of the South China Sea unmatched by any of its claimants.

Additional radar coverage is provided by rotational deployments of PLANAF Airborne Early Warning (AEW) aircraft to Hainan, with Shaanxi KJ-200 AEW aircraft regularly observed on the ground at Lingshui. Together, these radars will be able to provide China with an early warning capability unmatched by rival claimants, and will certainly complicate even U.S. air and naval freedom of navigation operations.

The KJ-200s were seen during the 2014 Haiyang Shiyou 981 standoff, operating alongside a handful Shaanxi Y-8J/X maritime patrol aircraft. These aircraft normally belong to the 2nd Naval Aviation Division based at Laiyang or Tuchengzi with the PLAN’s North Sea Fleet, but appear to be semi-permanently attached to the SSF.

Taken together, these developments would appear to indicate that, should China declare a South China Sea ADIZ, it is well on its way to being able to properly police and enforce it, unlike the case with its East China Sea equivalent. As noted by the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, the development of new runways and air-defense capabilities appear to be part of a long-term anti-access strategy by China which “would see it establish effective control over the sea and airspace throughout the South China Sea.”