For 72 years, it was missing in action. The Navy torpedo bomber rested on the sandy bottom off Palau’s coast, its fuselage violently broken from anti-aircraft fire amid heavy fighting of World War II.

Its presence there in the South Pacific went unnoticed until this spring, when a volunteer team of divers, historians and oceanography experts found the wreck. After some research and calculations – plus some high-tech sonar – the team determined the aircraft was a three-man TBM-1C Avenger that had crashed during a bombing run in July 1944.

That single discovery, while a drop in the bucket of more than 17,000 naval wrecks, is among the latest to begin the long process of finding answers about what happened to the Avenger and, perhaps, closure for the air crew’s survivors.

It began when a curious Patrick J. Scannon, an aviation buff, scuba diver and physician who founded a California company that discovers and develops antibodies. But naval history is his passion, particularly finding World War II wrecks in the South Pacific, where the pristine blue-green waters can mask graveyards of worn warbirds long forgotten by time.

In 1993, Scannon joined a diving friend to locate an armed Japanese trawler sunken off Palau, near the Philippines, on July 25, 1944, by former President George H.W. Bush, then an ensign piloting a TBF Avenger bomber. He found a broken aircraft wing of a downed Army Air Corps B-24 that hadn’t been recorded, and he soon searched for other aircraft wrecks off Palau. In 2000, he founded The BentProp Project “to make sure that that kind of sacrifice was not forgotten,” he told USNI News. The group counts on two-dozen active volunteers and donations to support and fund the work, which “is not an insignificant effort.”

Discovery of wreckage is just the first step to determine what happened to the aircraft. “It becomes quite a detective story,” said Scannon, who is withholding the location and unit details to secure the site and protect the aircrew, whose identification and names are yet to be verified by the Department of Defense.

As luck would have it, the Avenger Scannon’s team found was identified with the help of detailed squadron logs and other historical records including Japanese archives. With those details, the team was able to calculate possible flight paths and glide slopes to identify potential wreckage areas.

Advances in technology and data mining helped locate the bomber. Divers used a REMUS 100 autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) and high-frequency side-scanning sonar in the shallow waters about 80 to 90 feet deep. Specialized sensors helped draw an image of the ocean floor.

“We had six different aircraft we were looking for in the particular area,” said Eric Terrill, a diver and oceanographer with Scripps Institution of Oceanography and director of its Coastal Observing Research and Development Center. Over several weeks, the diving team did numerous side-scanning surveys, using historical records, after-action reports and other analyses to find probable areas of wrecks. “There were just so many targets,” he said, from the anomalies in the sonar images.

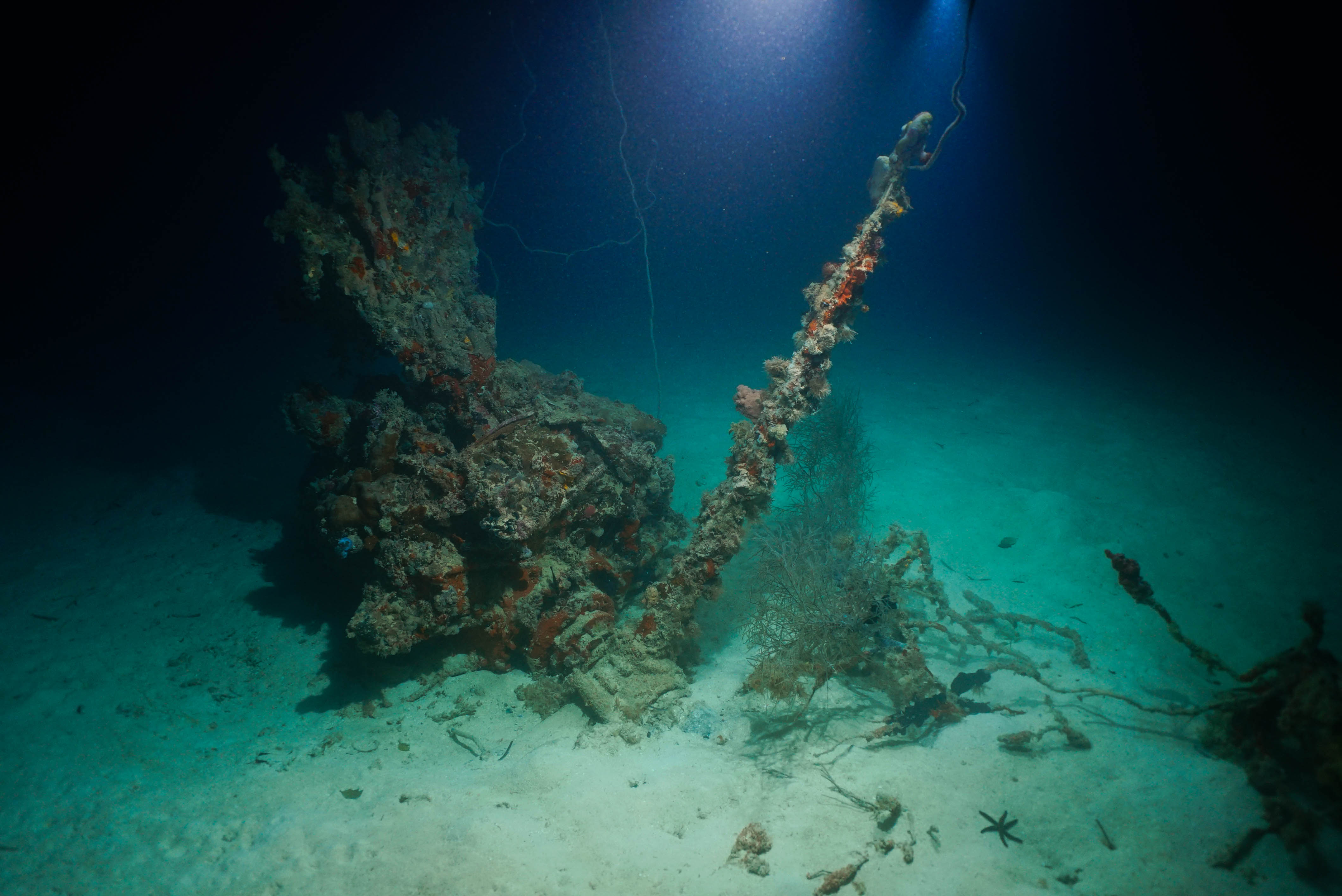

Their adrenaline pumped when they dove to a possible wreck for the first time, Terrill said. What he saw “was clearly man-made,” he said. “It was humbling. You’re excited that we’ve been successful, but you are really coming to hallowed ground.”

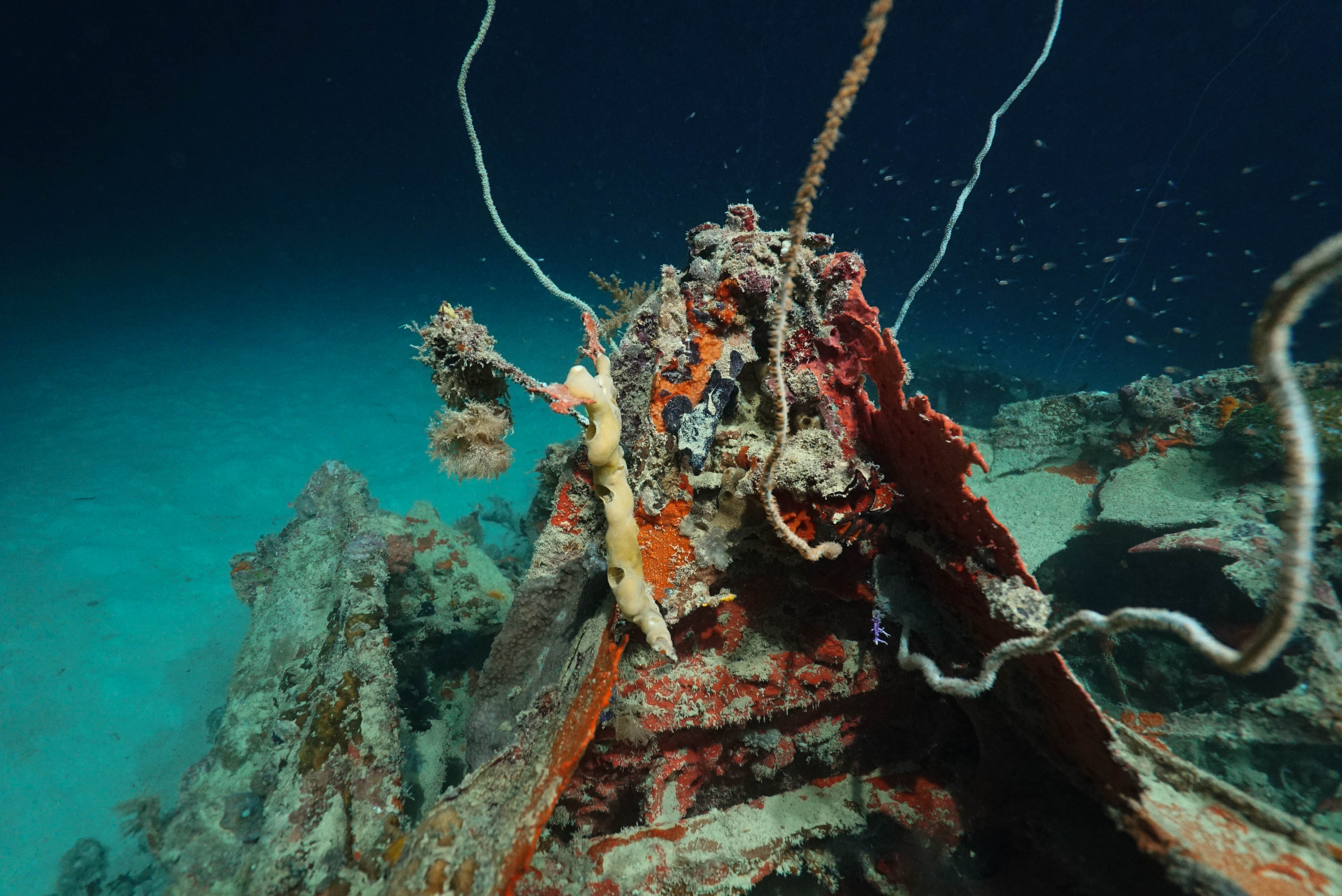

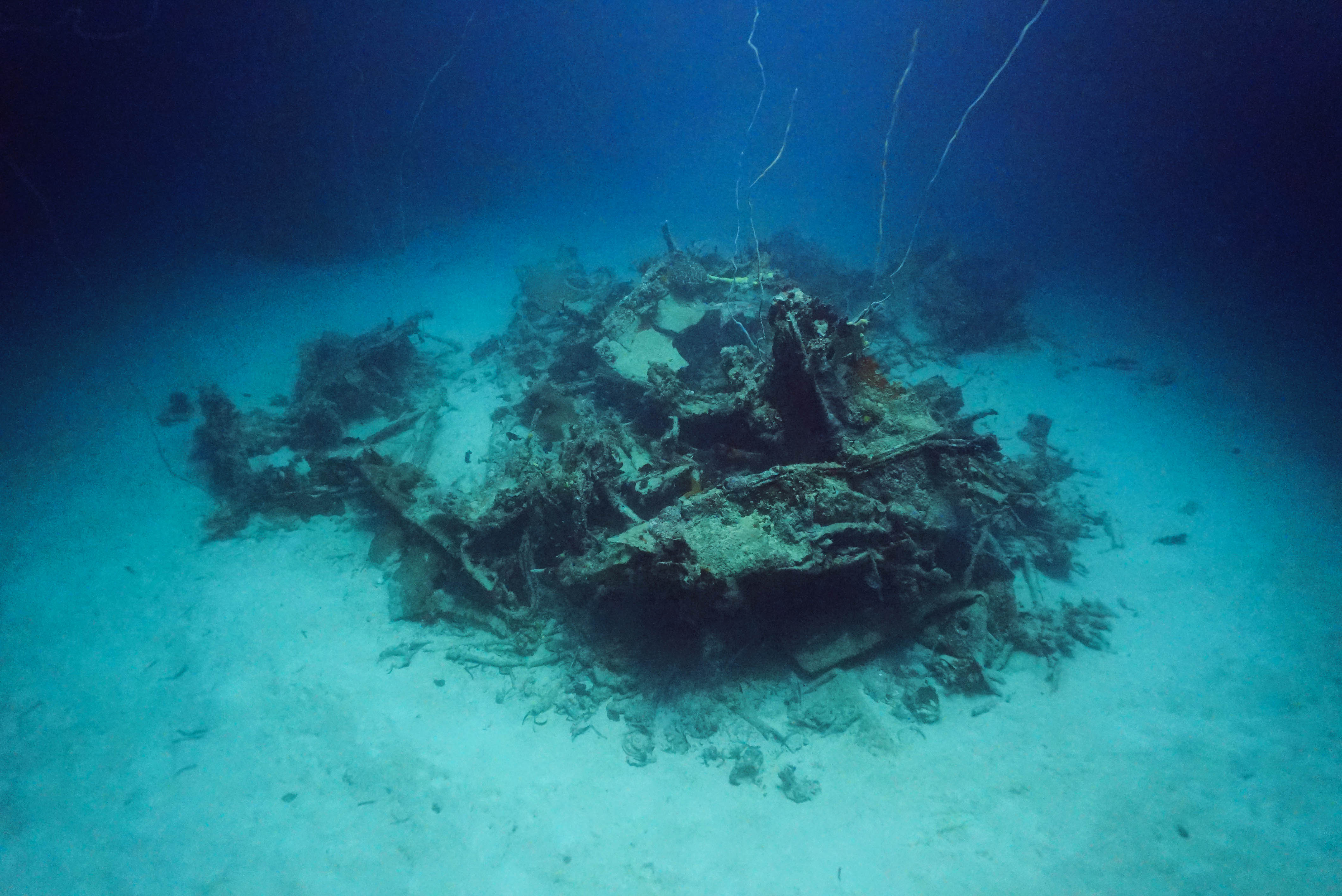

The Avenger had settled into the sand. For decades, it has provided a harbor for sea life, its surfaces broken or dented and mostly covered by algae and corals.

The bomber, Terrill and two engineers later estimated, had been flying at about 4,000 feet and was descending at a high angle after it lost a wing from anti-aircraft fire. It violently crashed into the water based on the wreckage footprint spread across a 20-meter by 20-meter area. The fuselage was split in half, and “we could see substantial fire (damage) in the main debris field,” Scannon said. Divers could see the cockpit cage and gun turret was thrown from the airplane by the impact. A wing had broken off, but the team later found it 900 meters away. Did any of the crew manage to bail out, or survive? Those questions remain unanswered.

“A crash site, even if it happened 50 years ago, is still something of a detective’s work,” Robert S. Neyland, who heads the undersea archeology branch head at Naval History and Heritage Command in Washington Navy Yard, told USNI News.

Once it was determined it was an Avenger, the BentProp team completed the site survey, compiling historical documentation and after-action reports that Project RECOVERY gave to the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) in April. Project RECOVER is a collaboration among BentProp, the University of Delaware researchers and Scripps/University of California-San Diego. The team works under an agreement with DPAA to share site data, as well as work with the U.S. government to conduct missing-in-action related searches.

“To proceed with forensics, all three agencies will be involved,” Scannon said, referring to DPAA, Naval History and Heritage Center and Palau’s Bureau of Arts & Culture, “and it’s a true forensic recovery. It’s treated in the same manner as crime scenes are treated. It’s very formal.”

The Hawaii-based DPAA would determine whether to recover any remains or artifacts, a process that could take years. Although Vietnam remains a priority for the agency, DPAA plans to deploy 24 investigation teams and 57 recovery teams to 16 other countries including Palau during fiscal 2017, according to a June 23 briefing at the annual POW/MIA Families conference in Virginia. The agency, in its second year of a restructuring, is under pressure to step up its efforts and show results. Some 83,000 Americans remain missing since World War II, which accounts for more than 73,100 MIAs.

Among DPAA’s latest focus is collaborating more with private groups and researchers, which could benefit from continuing interest in naval history particularly among local residents with in-depth knowledge of local waters and history. “There are groups like BentProp and others that go out and they take it as their mission,” Neyland said. “In most cases, I’d say it’s a big help.”

“BentProp is very professional. They use principles of archeology and have archeologists involved,” he said. “With a long list of wreck sites, “we have to pick and choose what we have time to work on. So what they do is very, very helpful to us.”

The Navy routinely works and shares information with the agency, which would determine whether the wreck site is explored further. On the latest TCM-1C wreck, “it may be an outcome in the future,” Neyland said. But no decision is yet made.

Just how many aircraft – U.S., allied or Japanese – and ships are in those Palau waters isn’t clear. The command’s underwater archeology branch has the lead for managing more than 2,500 shipwrecks and 14,000 aircraft wrecks globally, according to the Naval History and Heritage Command. On any given day, Neyland said, he and NHHC teams are working through numerous investigations, historical records and data, from a possible wreck in the Arctic to downed aircraft in Florida and plane in Montana. “Even though these things come up, there’s usually not a quick resolution,” he said.

Every wreck is considered U.S. government property, hands-off for anyone other than official or permitted recovery efforts, if undertaken. “These wreck sites are often the final resting places of sailors who paid the ultimate sacrifice,” the command states on its website, and these “carry significant historical importance or may contain hazards such as oil or unexploded ordnance.”The Navy maintains jurisdiction and responsibility for underwater wrecks, said NHHC spokesman Paul Taylor.

A recent revision to federal law that preserves sunken military wrecks – in effect since March 1 – requires permits to do any “intrusive activities” at a sunken wreck for “archaeological, historical, or educational purposes.” Wrecks “are not to be disturbed, removed, or injured, and violators may face enforcement action for doing so without authorization,” officials said last year in announcing the policy change. Also, “activities such as fishing, snorkeling and diving which are not intended to disturb, remove, or injure any portion of a sunken military craft are still allowed without the need for a permit.”

Project RECOVERY’s work is far from over. “We have a very long case list … that’s now 100 sites long,” Terrill said. “We’ve been cataloging a lot of search areas.” Newer technologies and sensors aid efforts and create more accurate data for ongoing searches and analyses, he added. Every wreck search, investigation, remains and artifact identification and recovery takes time, and that work requires funding. The Avenger project was covered by donations and funding from Air Force Heritage Flight Foundation founder Dan Friedkin.

BentProp has joined in 17 expeditions since 1999 and helped locate several crash sites where, in one case, four missing-in-action service members were recovered and repatriated. The group conducts “flag ceremonies” on the water to honor those lost. Whatever the military’s decision with this latest Avenger discovery, “we hope and look forward to the day where we can deliver these flags” to the relatives,” Scannon said. “We think it’s important to always have the families in mind.”

“It’s a very somber kind of adventure,” he said, “because you never lose sight of what we are doing.” Family members he’s met often are as emotional as if their loss was recent, he added, noting “almost every home I’ve been to has had a place of honor for their missing.”