USNI News recently asked its readers to weigh in on the question, “What is the greatest innovation in naval technology and why?” More than 160 readers responded and with nearly 3,000 votes and the results are in.

Aircraft from the Sea

The number one answer was “aircraft at sea on an aircraft carrier.” As noted by a reader, it “allows the Navy to be a strategic asset, it gives the leadership flexibility in responding to international crises. Aircraft are effective against air, surface and subsurface threats, which no other weapon system/platform can claim. It has a reach far beyond that of any gun, it can be more precise than any missile, and it is recallable if the circumstances of its employment change. Its versatility is unmatched in the history of naval technology.” The value of aircraft to naval warfare was not immediately recognized, though forward-thinking strategists like Brigadier General “Billy” Mitchell had foreseen the necessity of air power. It was not until World War II that the real value of aircraft became evident to many.

Interestingly, Admiral Arleigh Burke (1901-1996) had once posed a similar question to Admiral Marc Mitscher (1887-1947). Mitscher, one of the Navy’s pioneer aviators and commander of the Fast Carrier Task Force in the Pacific, Burke recounted in an Oral History interview with the Naval Institute in 1979, was unhesitant in his belief that pilots had become “the most important thing in battle.”

Steam Propulsion

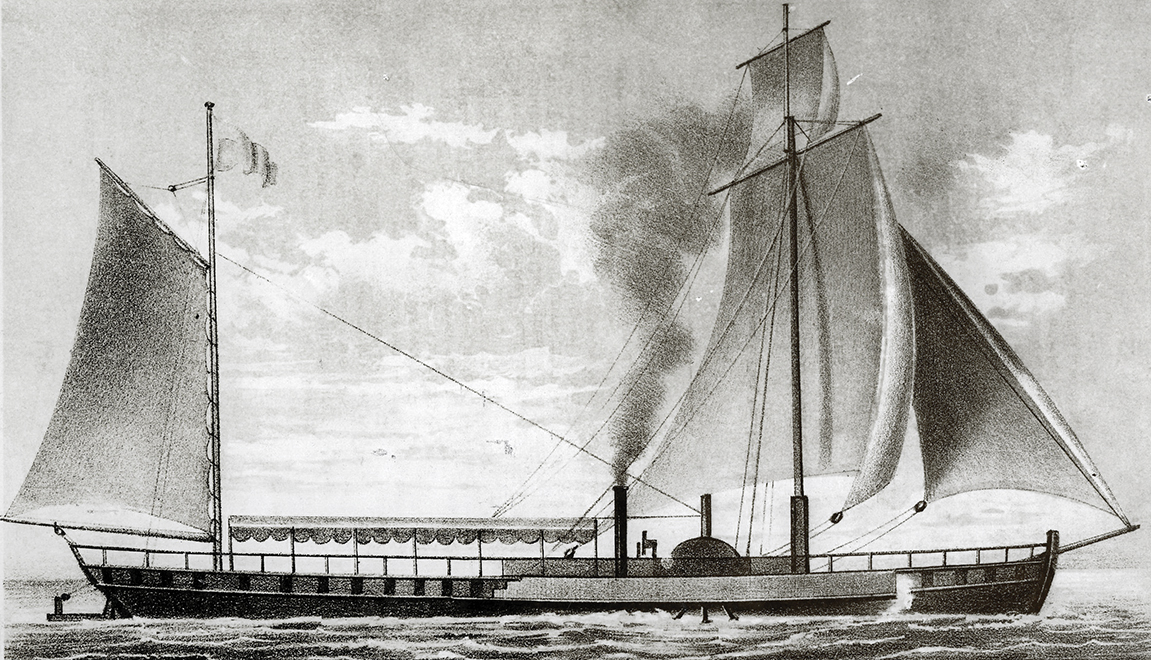

Another well-recognized innovation in the survey was the advent of steam propulsion. This “freed ships from the vagaries of the winds and increased overall speeds.” The reliance on wind power for propulsion was a known but dangerous fact of sailing and naval warfare for millennia, and history is replete with examples of ships succumbing to storms, such as the famous Kamikaze typhoons, or being stranded in the Doldrums for want of wind and tide.

But in the early 19th century, inventors like Robert Fulton began to apply the power of the steam engine—known since the early 1700s—to naval propulsion. “The application of steam propulsion to ships,” noted one Proceedings writer, “restored the tactical mobility which had been lost when the oar was discarded for sail. It gave fleets a temporary superiority which momentarily offset their losses in relative strategic mobility.” Yet for decades seagoing vessels retained their sails, and steam was more or less an auxiliary apparatus. But over time, the effectiveness of steam against Mother Nature’s fury became more than evident, and sails were largely abandoned.

Nuclear Propulsion

Much as steam propulsion permitted ships to move under their own power, nuclear propulsion, readers recognized, revolutionized surface and submarine tactics. Developers of atomic energy recognized the potential for nuclear power to provide long-term sources for energy without the need for refueling, as coal- and liquid-fueled ships had relied on for over a century. Nuclear energy, without the need for frequent refueling, offered the possibility of “continuous cruising at top speeds, unlimited cruising radii, and practically absolute freedom from fuel logistics.” Ships such as the USS Nautilus (SSN-571) and Enterprise (CVN-65) “allow[ed] navies to do what navies do best—project national power overseas in support of foreign policy.”

Navigation and Navigating Technologies

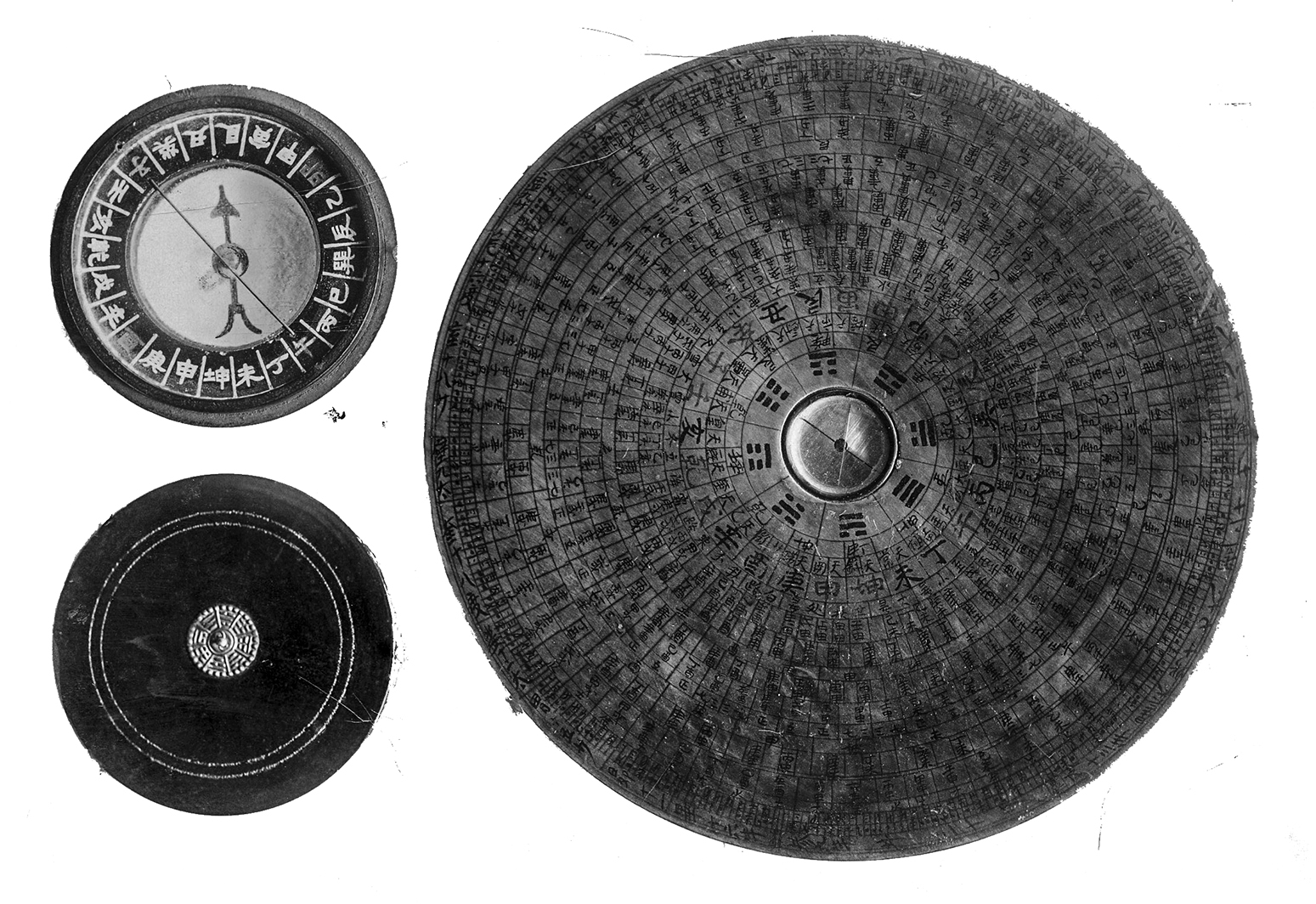

Many readers recognized the critical value of navigation on the seas. “Until seafarers could comfortably navigate the seas, commerce and naval warfare would always be limited to close in-shore,” one reader noted. Ancient navigators such as the Phoenicians and the Chaldeans found their bearings by referencing the positions of the stars and sun, and by hugging the coastline for recognizable landmarks which allowed them to explore the coasts of Britain and sail around the Horn of Africa.

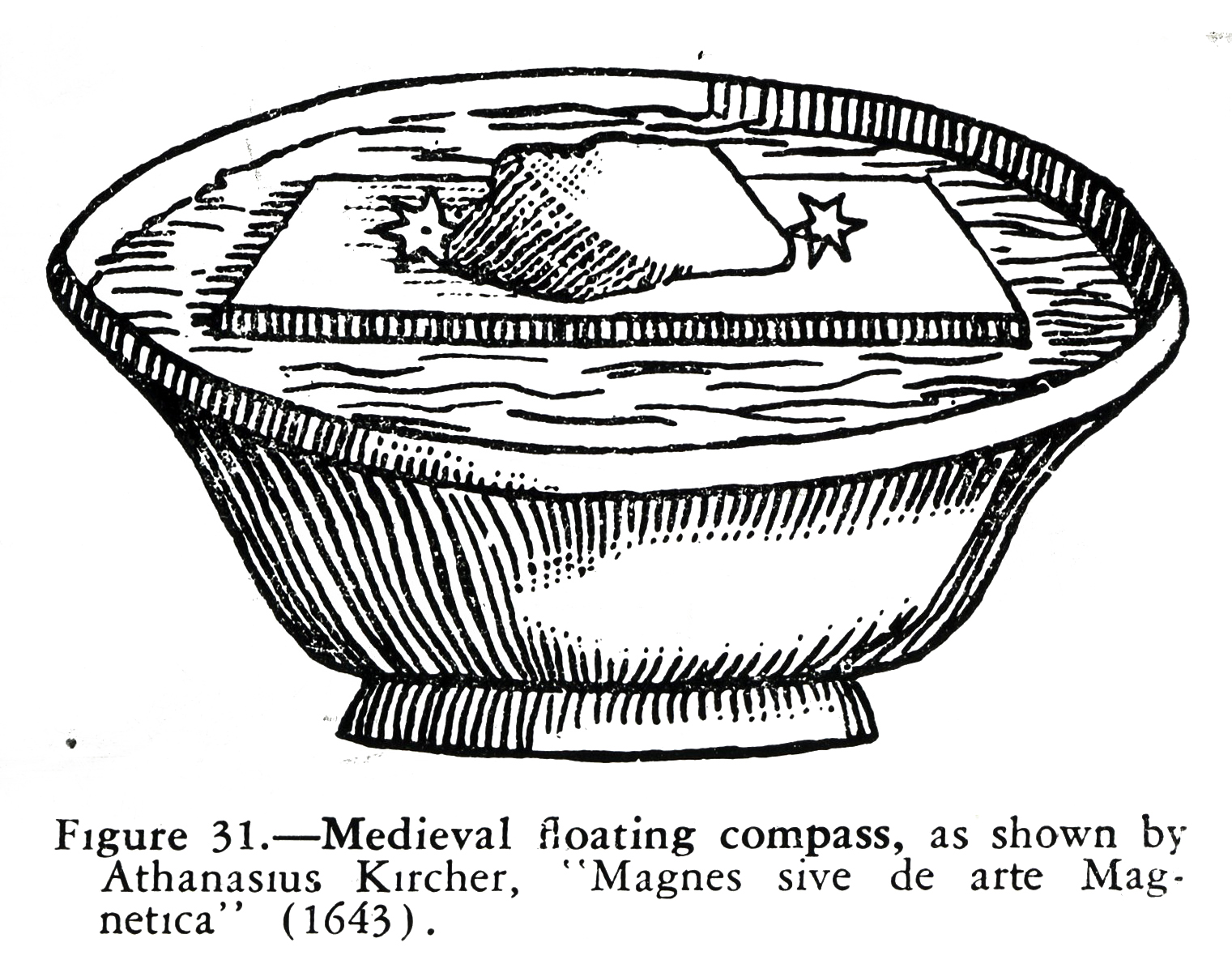

But it was not until the development of magnetic compasses that the first intercontinental voyages could occur. The magnetic properties of lodestone were understood as early as 400 BCE, and it is thought early Viking and Roman navigators harnessed those properties for navigation, but the earliest confirmed remarks to its use date to ancient China, and instances of “‘South-pointing chariots’ are said to have been used ashore in warfare about 800 A.D.” Chinese compasses and navigation charts, once described by one European as “very useful when once understood, and not so rude as their appearance indicates,” had spread to Europe by the 13th century, and in time allowed the Occident to largely control the seas for centuries.

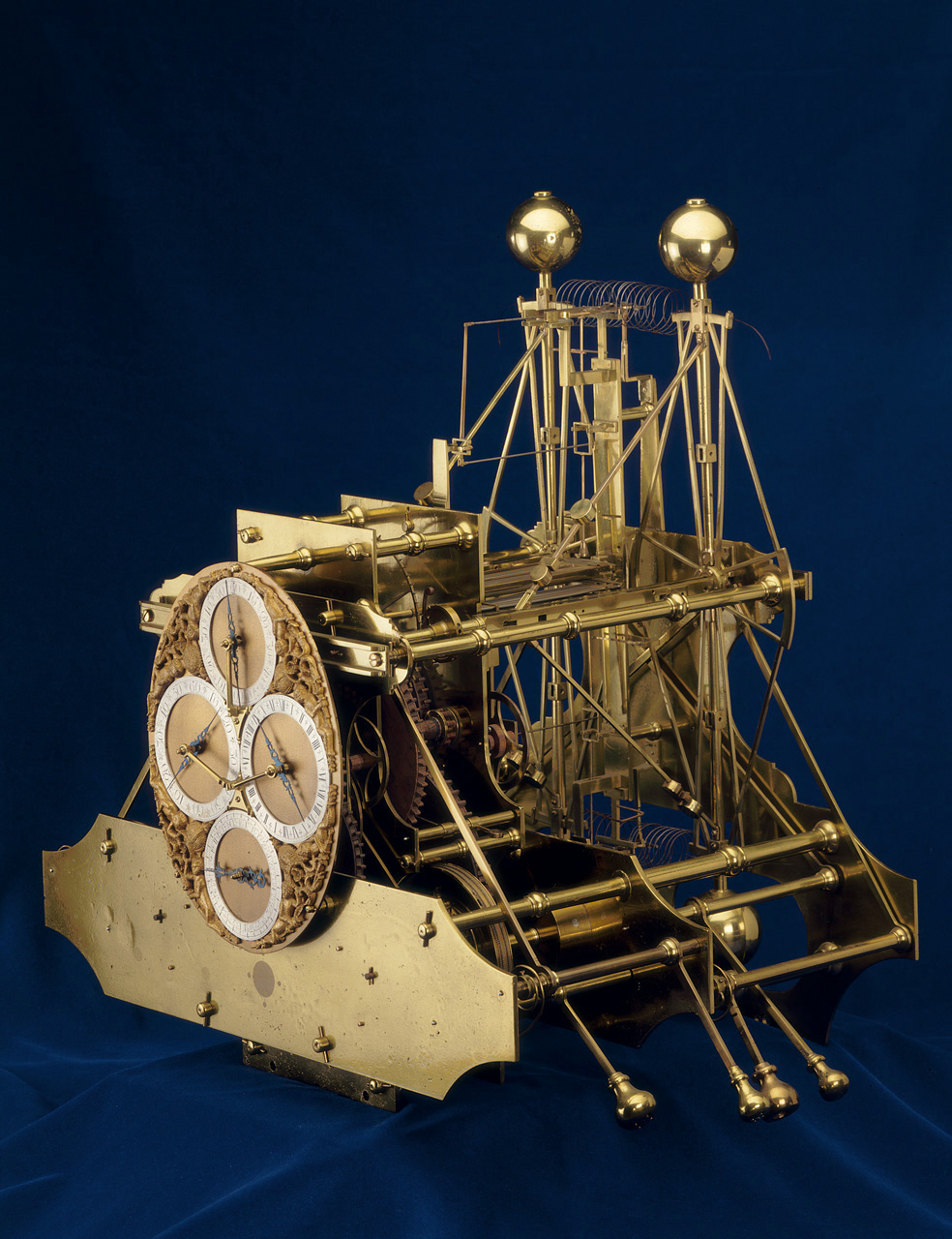

The compass and celestial navigation really only provided—with any accuracy—just half the necessities for navigation. In order to determine the longitude of one’s position at sea, an accurate timekeeper was needed. Thus, readers were quick to recognize the development of the chronometer by John Harrison in the 18th century as a monumental innovation in the history of navigation and the world’s navies. With that accurate timekeeper, built to withstand the rocking forces and other impacts of the shipboard environment, “the art of navigation became something more than the crude approximations of former times.”