Consumed with long-running irregular warfare challenges, the Pentagon took its eye off the ball with respect to maritime warfare, particularly against hostile warships.

The Navy is stuck with an obsolescent antiship cruise missile that is outranged by newer systems fielded elsewhere, and the U.S. Air Force lacks an antiship capability that can be fired from beyond visual range. Understandably, both services are now playing catch-up, and are searching for solutions that will allow the Joint force to reliably and effectively neutralize surface combatants. But the urge to focus on neutralizing enemy warships has dramatically constrained concept development to focus only on the tactical task of sinking warships and less on the strategic value of maritime interdiction.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in the realm of mine warfare, which has languished in a technological backwater for four decades, starved of resources and relegated to the junior varsity bench. However, a PACOM is directing a joint effort to combine legacy mines with precision guidance and standoff capabilities, introducing the Quickstrike-J and the Quickstrike-ER.

Recent attempts to modernize the capability by adding precision and standoff capability ran into objections on the Pentagon’s third floor because of a presumed limited applicability of mine warfare against warships. But this focus on antisurface warfare (ASuW) misses the whole point of offensive mining. Placing minefields in enemy waters is rarely about sinking warships, although that has proven effective. It is more about interdicting maritime traffic for strategic effect, starving vital industries, interfering with logistics flows and making every voyage to or from a hostile port a potentially risky endeavor.

Viewed from that perspective, recent demonstrations of advanced mining capability have a staggering potential to revolutionize maritime warfare, and deserve close attention from strategists and policymakers in the Department of Defense.

Capturing the Precision Revolution

The primary method for mine emplacement for U.S. forces is aerial delivery. The majority of the mine inventory is simply a cost-effective conversion of a general-purpose bomb into a mine. The Mk-80 series of bomb bodies are the warhead sections for the vast majority of air-dropped weapons, and have been since Vietnam. Designed for low aerodynamic drag, the weapons come in four sizes (250, 500, 1000 and 2000-lbs) and have a wide variety of uses from the unguided “dumb bomb” to the GPS-aided JDAM, Paveway Laser-Guided Bomb and even the rocket-boosted AGM-130.

The bomb bodies have fuze wells in the nose and tail for the devices that detonate the weapon. When the fuze is replaced with a target detection device (TDD) and dropped into the water, it becomes a mine that sits on the bottom and waits for a victim. Called “Quickstrike” mines, they can be laid by trained crews at low altitude from the Navy’s P-3 and F-18, and by the Air Force’s B-1 and B-52. Minelaying accuracy is very low, with the parachute kits contributing to poor predictability. Air-laid minefields are this designed for a “random uniform distribution” and consequently require large numbers of mines (and multiple minelaying passes at substantial risk to the aircraft) to be effective. The design of the basic Quickstrike mine has remained static since the Vietnam War, with advances in precision that were applied to the bomb bodies completely ignored for the mine variants.

No longer.

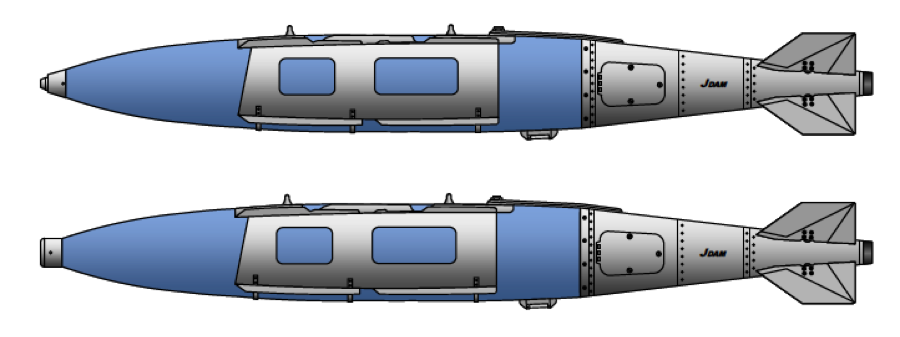

In September of 2014 Pacific Command (PACOM) demonstrated the Quickstrike-ER, a modification of the 500-lb. Australian winged JDAM-ER. Dropped from a B-52H, this was the first-ever deployment of a precision, standoff aerial mine. Now a parallel Joint effort between PACOM, the Navy and the Air Force has had its first success in the form of a 2000-lb. Mk-64 Quickstrike-J laid by a B-52H. Dropped in two variants, the Quickstrike-J can be laid from any altitude, by any aircraft equipped to drop the GBU-31 JDAM. In the case of the bombers, an entire minefield can be laid in a single pass without even passing directly over the minefield. The mines come in two variants, the Mod 0 with the legacy Mk-57 TDD and the Mod 3 with the new Mk-71 TDD. Both variants are assembled entirely out of components already in the US inventory, making these weapons possible without a protracted acquisition process.

The advent of precision aerial mines has outstripped the ability of mine warfare planners to design the minefields – no planning tools have yet been developed to take into account the ability to tailor a minefield to a specific body of water. What is certain is that precision minelaying will allow minefields to be shaped to maximize the threat in harbors, ship channels and other confined spaces. The mines have JDAM accuracy with respect to their selected impact point on the water surface and have surprisingly predictable underwater trajectories on their way to the bottom. Initial live drops showed a back-of-the-envelope circular error probable (CEP) of only six meters on the bottom. The ability to place a 2000-lb. mine within six meters of a specified aimpoint is unprecedented.

The goal of precision minefields is not to hunt warships. Warships, with their damage control parties, tight compartmentalization and designed-in damage mitigation features are about the worst possible targets for a mine. When USS Tripoli (LPH-10) hit a mine in Desert Storm, she was immobilized for less than 60 minutes and back on station 12 hours later. USS Princeton (CG-59) hit a pair of mines only hours later, and despite being immobilized her crew restored her systems and she resumed her role as the Air Warfare Commander within two hours. Tripoli stayed on station for six more days; Princeton was towed to port when relieved by another cruiser. They continued a long and successful streak – no U.S. warship has been sunk by a mine since the Korean War.

Not so vessels built to commercial standards. Commercial vessels tend towards small crews, large compartments, and lack both redundancy and onboard damage control. The US aerial mining effort against North Vietnamese harbors (codenamed Pocket Money) shut down the ports for the duration before the first mine was laid – all commercial traffic stopped when the US provided 72-hour advance notice. Navy aircraft laid 1000 and 2000-lb. mines on Haiphong harbor three days after that. No commercial ships braved the minefields until Operation End Sweep cleared the single mine that had failed to deactivate on time.

It was well that they did not. Even small, diver-carried “limpet” mines have proven lethal. In 1966, a mine attached to its anchor chain sunk the SS Eastern Mariner, and a command-detonated mine severely damaged the SS Baton Rouge Victory in the Long Tau river, killing the entire engine room crew and forcing the captain to beach the ship. Rainbow Warrior was sunk in Auckland by a pair of limpet mines attached to her hull. The unfortunately-named Sri Lankan naval auxiliary Invincible was sunk by a single limpet mine in 2008. Operation Starvation, the aerial mining campaign against the Japanese home islands, sunk or damaged 1,250,000 tons of shipping. Even minor damage essentially ends a voyage as a commercial vessel will often proceed to the nearest suitable port rather than the planned destination.

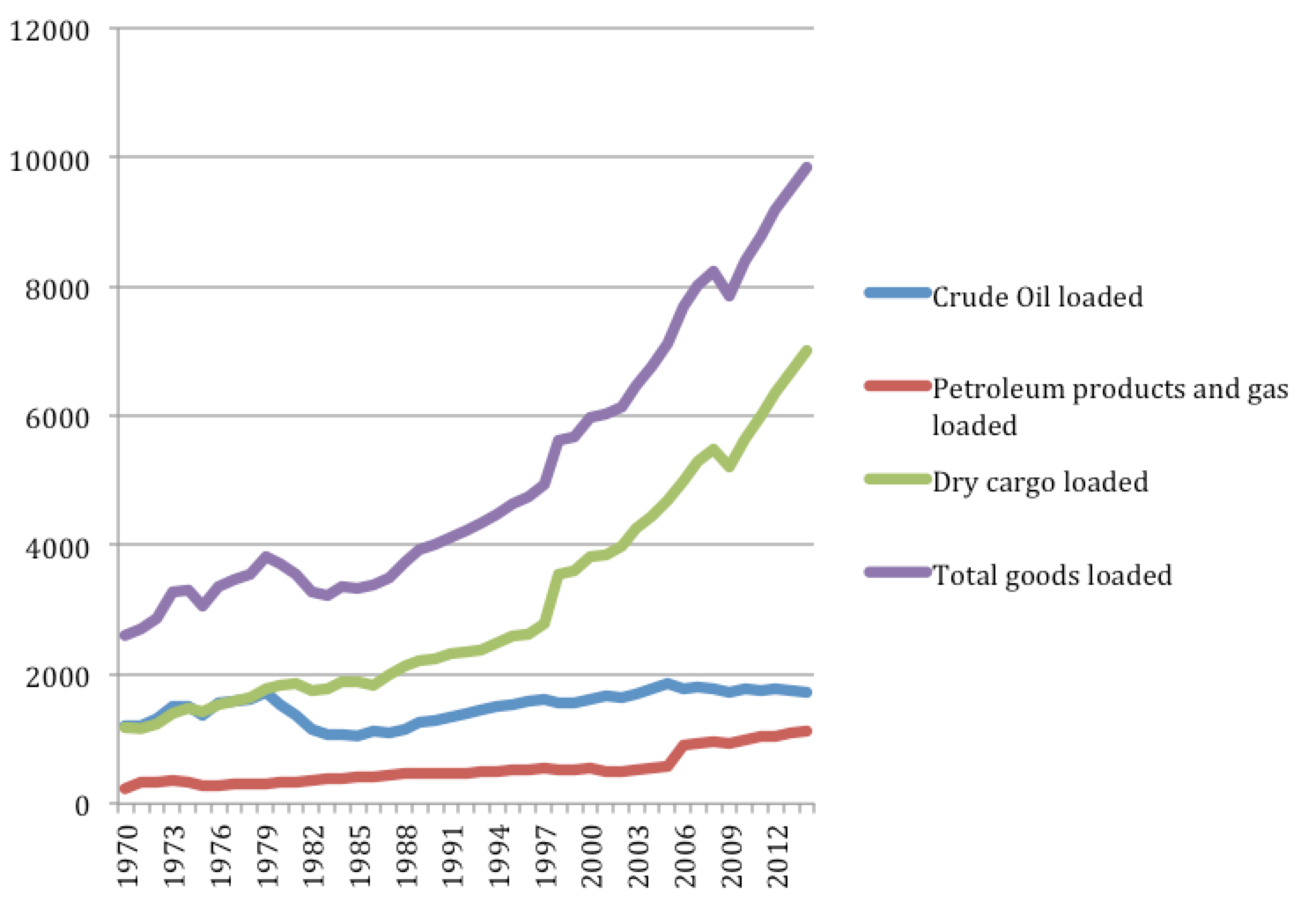

With the advance of globalization and the resultant expansion or maritime trade has come an explosive growth in maritime transportation. From a strategic standpoint, this is an asymmetric exploitable vulnerability, in that not all major powers are equally dependent on maritime transport. China is so dependent on maritime trade that it might as well be an island nation, transporting over 98 percent of its external trade by sea and also reliant on coastal and internal waterways for a significant amount of local freight movement. The commercial vessels that ply this trade are uniquely vulnerable to interdiction via aerial mining.

With the Quickstrike-J, every JDAM-capable aircraft is a minelayer. Emplacing minefields to impede merchant traffic can often be done without penetrating the air defenses that might be expected at major naval bases. According to the 1907 Hague Convention, mined areas must be declared but not all declared areas must be mined, providing a useful degree of ambiguity. When the target set consists not of naval vessels with must transit but rather commercial hulls which may transit, the accurate placement of large naval mines can have an interdiction effect massively disproportionate to the density of the actual threat.

The Quickstrike J and the smaller (but longer ranged) Quickstrike-ER are the largest technological leaps for aerial mines since the Luftwaffe introduced the magnetic mine in 1939. Assembled from off-the-shelf components, they may provide combatant commanders with an accurate, responsive and custom-tailored capability to support a maritime interdiction campaign. The Department of Defense should remain cautious with its concepts, lest it be disappointed by trying to fit a square peg into a round hole while ignoring the appropriate use for these weapons. Precision aerial mining is a brand new concept that is still in the test phase, and could easily be stuffed into a forgotten cupboard if the implications of the weapon remain poorly understood and strategically misapplied.

Yes, advanced mines may be used to target warships (including submarines), but this is not the primary mission. The purpose of these weapons is to paralyze the critical maritime traffic upon which so many nations depend, providing substantive strategic effects with relatively low investment in weapons and sorties. Precision aerial mining is still in its infancy, but for the moment it is a valuable, US-only capability which has incredible potential.