THE PENTAGON – The future attack submarine fleet will have a longer reach, deliver a range of kinetic and nonkinetic effects and be better able to share information without compromising stealth, the Navy’s Undersea Warfare Director (OPNAV N97) told USNI News this week.

Rear Adm. Charles Richard said the attack submarine fleet represents the Navy’s greatest asymmetrical advantage, and the undersea community needs to work to maximize that advantage as technologies and the operating environment evolve.

“How do you take greater advantage of the fact that you have access?” he said in an interview in his office on Tuesday.

“How can I improve my sensing capability? How can I grow longer arms with better missile capability, better torpedoes?”

On the weapons side of this effort, Richard said the Navy is working on several projects that will increase the strike range of the attack submarines. The service is adapting the Tomahawk Land Attack Missile (TLAM) to have an anti-surface ship attack capability, which will benefit the Navy’s surface ship and submarine fleets. Richard said the Fiscal Year 2017 budget request also contains funding for innovative torpedo prototype work, which would look at longer ranges, greater capability and multiple payloads.

Even the existing inventory of torpedoes is set for improvements, with the Navy creating a technology insertion program – modeled after the Acoustic Rapid Commercial-off-the-shelf Insertion (ARCI) combat system improvement program for the submarines themselves – to increase the heavyweight torpedoes’ sensors through hardware and software upgrades.

Looking ahead, Richard said that understanding how submarines use nonkinetic effects is one of his top priorities. The Navy needs to decide “what capabilities would be of benefit to a combatant commander in a situation that is somewhere in the gray between peace and all out war type conflict,” and which of those effects might be best delivered by a submarine.

Submarines today, and even more so in the future, will not only deliver weapons but will also carry a family of unmanned underwater and aerial vehicles to help extend their area of influence. Richard said the Navy has bought about 150 3-inch unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and about a dozen 21-inch UAVs that are fully integrated with the submarine and send information back. The submarine community also has 16 21-inch Littoral Battlespace Sensing Autonomous Underwater Vehicles coming into the fleet for additional intelligence-gathering underwater.

In the future, though, Richard said there will be more UUVs, but “they won’t always come by submarine, they may come by a number of mechanisms – you may launch them from a surface ship, they may be launched from the pier. It’s just a capability, a node in an undersea constellation that will include the seabed, fixed distributed systems. Not all UUVs are going to look like little submarines, there’s a bunch of different ways to put this effect in there.”

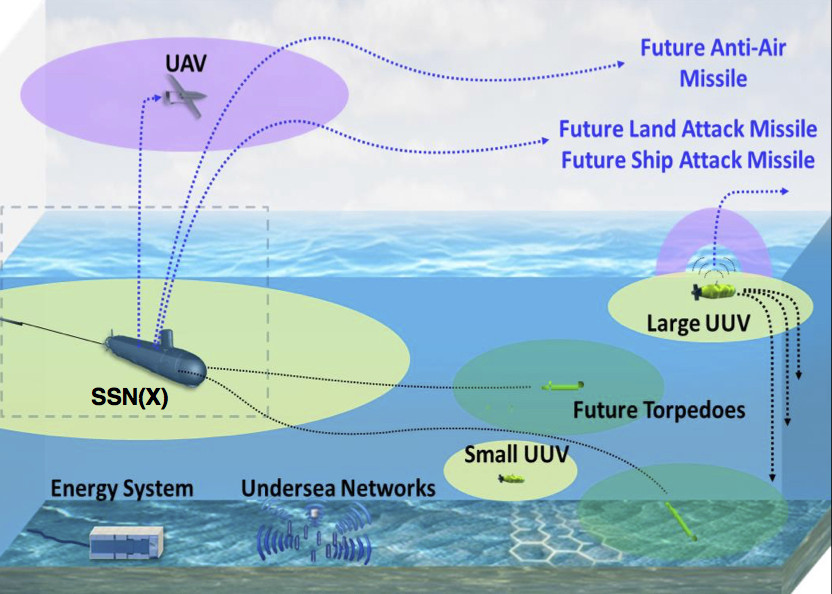

This idea plays into Richard’s view of the undersea domain – operations shouldn’t be platform-centric but rather domain-centric. In a graphic of future underwater operations, Richard said “the submarine’s not in the middle of the picture. That’s intentional to show that it is just part of a larger system that we’re putting out there.”

“In the end, what I have to get in an environment is sensing capability, command and control or decision-making capability, and effects. If you go back far enough in time, the only way to get it there was to bring it with you. That’s no longer true,” he said.

“I can put sensing into the undersea environment by having it mobile and carrying it on a submarine. I can put it potentially on an unmanned vehicle. I can fix it, distribute it and drop it in; maybe it has a little mobility. Or I can fix it to the seafloor. That’s the question you have to go ask yourself, what’s the best distribution of all of that.”

The Navy is hard at work starting to answer some of these questions. N97 released a report to Congress last month called “Autonomous Undersea Vehicle (AUV) Requirements for 2025,” which outlines with web of fixed and mobile undersea sensors, as well as charging stations on the seafloor and other support systems.

In addition to tackling current undersea missions – nuclear deterrence, anti-submarine and anti-surface warfare, strike, mine warfare and more – AUVs may take on new missions like deception, counter AUV, seabed warfare, electromagnetic maneuver warfare and nonlethal sea control. Some may be as small as today’s 3-inch vehicles, while others could be larger than seven feet across.

Richard said the Navy is identifying what technologies they should begin looking into for this 2025 vision. An N97 Future Capabilities Group was reenergized about a year ago and is leading the way in pursuing the ideas within the AUV roadmap.

Fielding this network of unmanned vehicles and seabed nodes will require advances not only in the unmanned vehicles themselves but also in undersea command and control, as well as a better understanding of how submarines can operate in the electromagnetic spectrum, Richard said, identifying that as another of his top priorities for the undersea warfare community.

“That’s the one we’re putting a lot of effort into, how do undersea platforms operate in the electromagnetic spectrum? So I see a lot of potential there for us to change our abilities, change our capabilities and make a bigger contribution to the force in that area,” he said.

“Several of my next [aspirational capabilities] involve electromagnetic spectrum, involve that command and control piece. LPI/LPD – low probability of intercept, low probability of detect – communications.

In some cases, a submarine is the only sensor the Navy has in an area. While at times it’s most advantageous to remain stealthy and not communicate back to the fleet, the ability to use the EM spectrum in more situations “to feed [information] back to a larger picture at the operational level or a fleet scale is something we’re looking really hard at.”