You are out there somewhere. Perhaps you are currently serving in a senior national security position. You may be advising one of the current presidential candidates on defense policy. You could be a leader in industry, or academia. You may be working at a think-tank or serving as an elected or appointed official in state or federal government.

You are the next Secretary of The Navy.

This article is not intended to give you policy advice. The president who appoints you and the Secretary of Defense you will serve under will have their own strategic view of the world, the United States, and the role the United States Navy should play in that world. You will have your own personal agenda; which programs you see as priorities, which areas of the Navy and Marine Corps on which to focus your most valuable resource—your time. My goal, as one who served in the secretariat as a uniformed officer and has observed its workings for many years, is to make that time, and your tenure in office, more effective.

Step 1 – Your Team

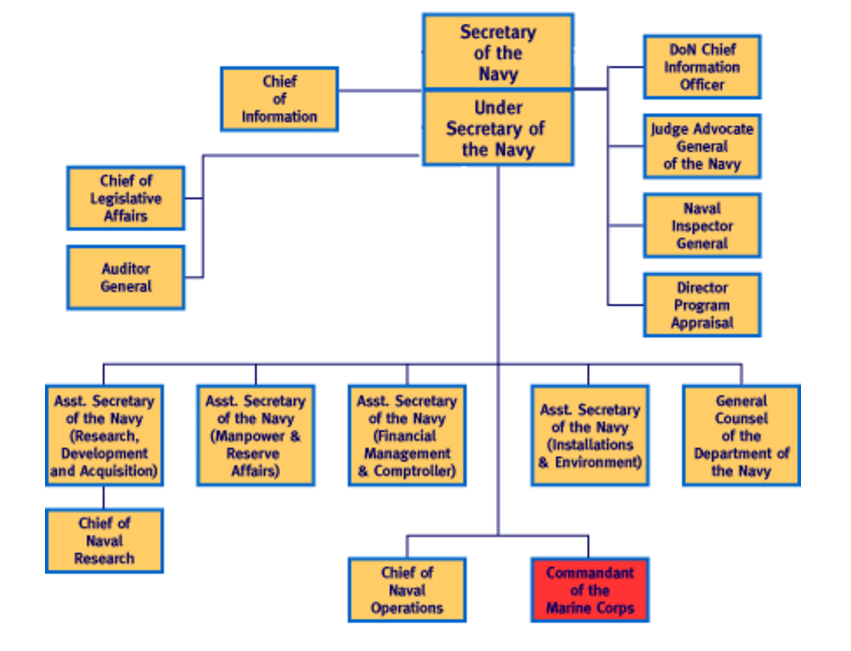

The Department of the Navy (DoN) has seven Senate-confirmed presidential appointees at the top of its civilian leadership. Beyond the secretary, there is the under secretary, 4 assistant secretaries, and a general counsel. That is six people that you will initially help select to lead and manage the hundreds of thousands of sailors, Marines and civilians in the DoN. In addition to their interactions with the members of the DoN, those six appointees will also be critical in your engagement with the rest of the Pentagon bureaucracy, other federal agencies, Congress, and the media. Also, they are all presidential appointees, so your initial relationship with the White House and SECDEF will be put to the test. You will want to start early to fight for a team that shares your vision, complements your personal strengths, and mitigates your weaknesses.

An underappreciated aspect of Pentagon decision-making is how much personal relationships effect policy. If the political appointees who are your senior civilian decision-makers cannot communicate directly, quickly, honestly and supportively with each other, their staffs will not be able to maintain that link for them. Political appointees tend to come from a wide variety of backgrounds. Some are taken from industry or academia. Some are retired senior officers. Some are younger political actors, such as congressional or campaign staff, for whom a tour as an assistant secretary becomes an audition for potential higher political office in a future administration. As secretary, you will need to mold this team from likely disparate backgrounds into, as Shakespeare said in Henry V, “a band of brothers” (although today “band of siblings” is more likely and appropriate).

The most important member of your team will be your under secretary. The choice of an under will depend on what kind of secretary you want to be. For the secretary of the Navy, there are four groups of stakeholders that will require regular attention. The first is the senior decision-making bureaucracy of the Pentagon and the rest of the executive branch. The second is the Congress of the United States. The third is the sailors, Marines, and civilians who make up the Department of the Navy. The fourth is the news media. You, as secretary, have the time and talent to effectively engage, as best, two of these four. Once you identify which two will be your focus in office, pick an under secretary who will be able to engage the other two. As an example, if you have little experience with Capitol Hill, a well-respected current or former staffer, who either served one of the defense committees or worked for a member of the House or Senate who sits on a defense committee would be advisable. On the other hand, if you are a current or former member of Congress, you would look for an under with significant experience inside the Pentagon, such as a retired flag/general officer or member of the Senior Executive Service. The goal in an Under is to find someone to balance your experience base while at the same time have someone equally committed to your agenda as you.

After the under secretary, the next most important position in the secretariat is the service acquisition executive (SAE). In the Department of the Navy, the SAE is the assistant secretary for research, development, and acquisition (RDA). In the past 20 years the two longest tenured SAEs have been the late Claude Bolton, a retired Air Force major general who served for six years as the Army’s SAE, and Sean Stackley, a retired Navy captain who has been the Navy’s SAE since 2008. Not only are they the two leaders with the greatest duration of service, they are widely regarding throughout the defense acquisition community as highly successful in having brought effective management to their large, complex portfolios. I assert it is not a coincidence that the two most effective SAEs in recent history were the two with the most hand-on acquisition experience during their military careers. Secretary Bolton served on the Air Force’s SAE staff as a field grade officer and was both a major program manager and a program executive officer. Secretary Stackley, during his time on active duty, served on the Navy’s SAE staff and was a major program manager for one of the most complex ship programs of its time, the LPD-17. No matter how effective current efforts at acquisition reform become, the procurement of weapons systems will remain a highly knowledge intensive and specialized endeavor. A smart SECNAV will avail himself of someone who has personally managed complex defense programs for the DOD to serve as his SAE.

The general counsel (GC) of the Navy is the service’s most senior lawyer. The secretary of the Navy is his client, not, technically speaking, his boss. Attorneys in the federal government answer to a legal chain of command, so for purposed of legal advice and procedure, the Navy’s general counsel answers to the DOD’s general counsel. Most lawyers will tell people that the best way to hire an effective attorney is to get a referral from someone they trust. As SECNAV, the Navy GC will be the lawyer you hire to provide counsel to your efforts, so start by engaging a broad spectrum of legal practitioners whom you trust. Your Navy GC will need to have the capacity to both provide you effective and accurate legal advice on your actions as SECNAV and be able to manage the legal professionals, both, civilian and military, within the DoN. Civilian lawyers in the DoN are, to a very great extent, dedicated professionals who do their best to provide the legal advice that will help their clients accomplish their assigned missions. However, they are, as a group quite conservative in assessing the legal authorities provided to the DoN and are averse to seeing the DoN engaged in litigation. In general, this is a good attitude for civil service lawyers in a democracy; it serves to limit discretion of action to that explicitly authorized in statute or case law. You may at times need bolder legal advice. You will want a Navy GC capable of challenging the status quo without crossing the line into illegality. The bottom line: Hire a great lawyer.

Step 2 – Your relationships

The day you take the oath as SECNAV two of your most visible and influential leaders will already be in place: the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) and the Commandant of the Marine Corps (CMC). Service chiefs usually serve four-year terms, so you will inherit a CNO and CMC from your predecessor and likely have the opportunity to influence the selection of their successors. They are subordinate to you in the chain of command, but you will find they have a special relationship with many of the stakeholders, both inside and outside the Pentagon, with whom you will need to be successful.

Within the Pentagon, the CNO and CMC sit on the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS). They will likely have both a strong personal and professional relationship with the chairman and vice chairman of the JCS. The purpose of JCS is to represent the views and needs of the nation’s combatant commanders (COCOMS) within the Pentagon’s decision-making processes. The COCOMS are the customers of the military services as they will be the ones who will employ the sailors and Marines, ships and aircraft, and the rest of the military capability that you as SECNAV are responsible to man, train, and equip. You will need to both absorb from the CNO and CMC what the Joint Staff and COCOMS want from the DoN but also have your service chiefs educate their four-star peers on your vision for how the DoN will support the nation’s military needs. Within the DoN, the CNO and CMC serve as the primus inter pares of the flag and general officers in their service. Even among senior officers who do not report to the service chief directly, because they occupy joint billets or billets reporting to the secretariat, the opinion of their service chief will weigh heavily in their mind. Outside the Pentagon, Congress and the press will want to hear directly from the service chiefs. These decision-makers want to hear from senior uniformed leadership. The service chiefs bring long histories of operational experience and typically have had command at multiple levels. Congress relies on their candid judgments to shape the legislative process.

In addition to their vital relationships, the CNO and CMC exercise a high degree of autonomy unlike what even a senior executive would have in private industry. A service chief practically cannot be fired absent some obvious misconduct. He has already achieved the highest position in his service so he is not looking for his next promotion. While these chiefs work for you, they will often be asked to give their independent view of the issues you will want to drive to implement your vision. Great SECNAVs have understood this relationship and worked to foster a unified vision with the CNO and CMC. That takes three things; time, process, and collaboration.

First, time.

The SECNAV, CNO and CMC are all incredibly busy and will all have national and international travel commitments. A great SECNAV will make regular times for the secretary and the service chiefs to come together for briefings and discussion of the key issues on which clarity and unity of vision will be needed. Some of these will involve a significant presence of staff to present relevant information and some of this time will need to be just the three leaders together. Second, process. To make the time meaningful, the immediate staffs of the SECNAV, CNO and CMC will need a way to vet and prepare issues so that your time with your service chiefs is productive. I recommend taking notes from Gen. Stanley McChrystal’s recent book, Team of Teams.

Like the operational briefs McChrystal developed during his tour in Iraq, charter regularly scheduled, widely attended, and tightly focused meetings, that the senior aides to the secretary and service chiefs will chair and can use to identify and clarify the issues that merit your engagement. Third, collaboration. A great SECNAV will be influenced by his service chiefs at least as much as he influences them.

Great SECNAVs also understand the difference in the roles of the civilian and military leadership within the DoN. You as SECNAV, and your under and assistant secretaries, are members of the administration you serve. The senior military leaders are not. It is both unfair to them and unwise in a democracy to place your senior military leaders in the middle of policy disputes between the executive and legislative branch. That is your job. If you have done your work properly, the CNO and CMC will be giving their best military advice to the decision-makers in both branches influenced and imbued with the common vision and understanding you have helped develop.

Step 3 – Your Time

You likely already are a highly successful leader or you would not have earned the presidential nomination to be SECNAV. You already understand how much time you will need to eat, to sleep, to exercise and spend with family and other outside pursuits in order to keep yourself in the physical and mental condition required to be a productive senior leader. You will have identified the key stakeholders, in the Pentagon, in Congress, and in the media on whom you will focus much of your time. However, there are time consuming areas you will not want to overlook.

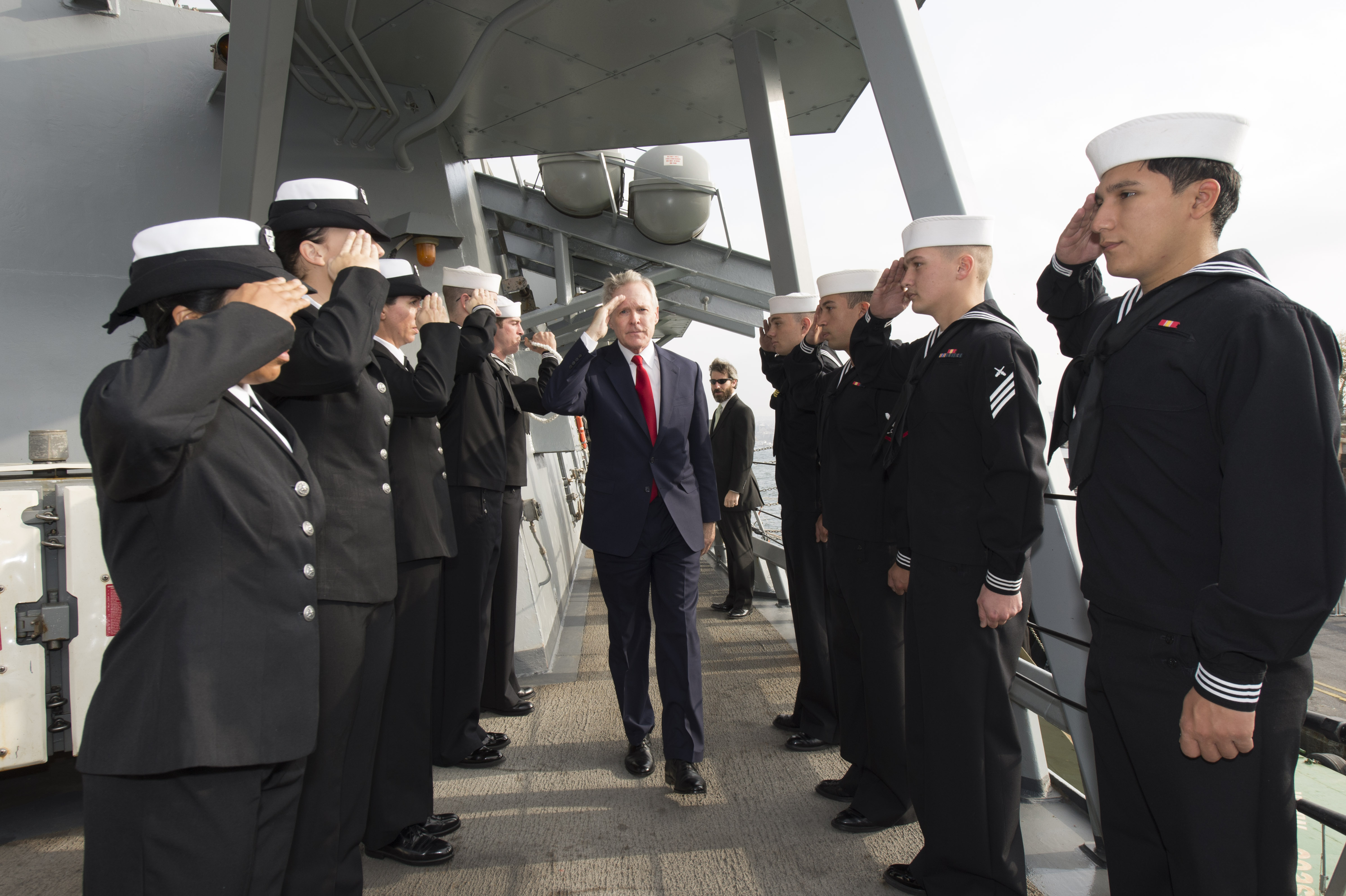

First, the sailors, Marines and civilians in the DoN, in America and around the world want to see their secretary. They want to know that the administration they serve values that service enough that the SECNAV and other administration figures visit their places of service and take the time to listen and learn from them. The SECNAV has an aircraft assigned to his use for a reason—put lots of miles on it. Second, do not get all your information from your staff. No matter how diligent and candid your immediate staff members are, the urge to groupthink inside the Pentagon is powerful. You will want to avail yourself of meetings with scholars, writers, scientists, opinion leaders, and industry leaders outside the federal government. Third, do not forget to read. Great writers produce insights on how the world works and how it is changing. When important books such as The Looming Tower and The Pentagon’s New Map are released, they need to be on your nightstand. Ask other leaders what they are reading as a way to identify what you will need to read to keep your understanding of the world current. Fourth, talk to your predecessors. Today, including the currently serving Secretary Ray Mabus, there are 12 living SECNAVs (not counting officials who held the position in an “acting” capacity). They can serve as a source of wisdom and perspective as you chart your course. While technology changes constantly, wisdom is permanent. Do not pass on the opportunity to avail yourself of the wisdom built over time by the previous holders of your office.

In addition to all the other demands on your limited time, do not forget the American people. You will be the administration’s top advocate for sea power and the sea services. America’s maritime strength is a vital component of our nation’s prosperity and security; however, precious few of our citizens understand that. A great SECNAV makes time to communicate with the American people though multiple media; print, television, radio, online, and in person. Educate the American people on how your vision of American maritime power matters to them in their lives.

Finally, enjoy your time as SECNAV. You have been entrusted to be the senior civilian leader of an organization that correctly advertised itself as a “Global Force For Good.” The sailors, Marines, and civilians who make up the DoN stand ready to respond to your leadership. If you bring passion and a willingness to learn to the job, you can accomplish great things. I look forward to serving under you.