In order for a coherent vision of modern American seapower to move forward in providing the lion’s share of this nation’s peacetime presence, shaping, deterrence and assurance needs, the Department of the Navy must become more efficient in its acquisition processes. It must be more nimble, more flexible, more accountable and faster.

Because it is currently not these things, the true value of American seapower is muddled and somewhat drowned out by the noise associated with the expense and waste of maintaining it. We believe that for a new vision of American seapower to deliver on the promise of efficiently and effectively delivering security and prosperity to the nation, radical changes to the acquisition system are required. While these changes could or even should apply across the Department of Defense, our concern here lies mainly with the Department of the Navy.

The current systems and processes used by both the Department of Defense (DOD) and the Congress in the acquisition of major defense programs suffer from differing timelines and multiple decision-makers. Accountability for key results is spread over enough different organizations that no single decision-maker has sufficient authority to be effectively accountable. Also, Congress and the Secretary of Defense lack the means for effective oversight, through which policy makers can be provided informed analysis on decisions that must either be ratified or reversed. Reemphasizing the role of the service secretaries and improving Congress’ visibility into the key points of the decision process can establish a more effective and accountable defense acquisition system.

The FY2016 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), with its renewed emphasis on accountability in acquisition, and the willingness of both Congress and the administration to look at new and innovative ways to improve the efficiency of the DOD, provides an opportunity to make meaningful reform in the area of defense acquisition. That reform centers on three separate but related processes that must ultimately be reconciled to achieve acquisition excellence.

The Joint Capabilities Integration Development System (JCIDS) defines the desired capabilities in what gets bought, and is controlled by the Joint Staff. DOD Instruction 5000.01, “Operation of the Defense Acquisition System” (commonly referred to as “The DOD 5000”) provides the process for how to buy major defense items and is controlled by the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics (AT&L). DOD Directive 7045.14, “The Planning, Programing, Budget, and Execution (PPBE) Process” (commonly referred to as “PPBE”) provides the process for how major purchases are budgeted and paid for and is controlled by the Under Secretary of Defense, Comptroller (USD [C]). These three processes move along largely independently, and exist in differing decision-making contexts.

The main reason those three systems remain disconnected is that they have different bases for their processes. PPBE is time-centric. That is because it exists for two reasons; first, to produce a budget for congressional action each fiscal year, and second, to track the expenditure of funds that expire at set intervals. The DOD 5000 is event-based. Designed by engineers to manage the acquisition process, the DOD 5000 processes are geared around observable engineering metrics to determine when key acquisition actions are ready to proceed. Finally, the JCIDS is capabilities and threat-based. JCIDS injects requirements for new capabilities at irregular intervals because in war, the enemy gets a vote. The acquisition model at work in the Department of Defense has three heavyweight players.

First, the Services (Army, Navy/Marine Corps, Air Force) man, train, and equip military forces. (There are a few DOD organizations, such as U.S. Special Operations Command and the Missile Defense Agency, that have special authority to accomplish part or all of the manning, training and equipping of military forces. What is said here about services and the service secretaries applies equally to them.)

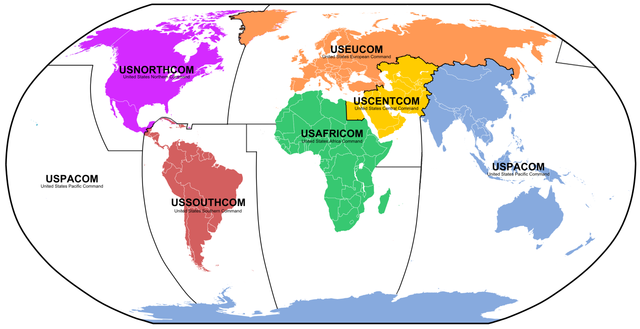

Second, the Combatant Commands (COCOM), whether geographic (e.g., U.S. Pacific Command) or functional (e.g., U.S. Transportation Command) employ military forces. In the context of acquisition, the Joint Staff exists primarily to represent the COCOMs to the services in the budgeting and procurement processes. Finally, the myriad parts of the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) exist to provide cross-service policy and oversight of the services and COCOMs.

Accountable Actors

Any meaningful attempt at unifying defense acquisition must address two key concepts. First, accountability. The FY2016 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) took an important first step in this area by assigning the services a greater role in the decisions that shape major defense acquisition programs. However, accountability is an often-misunderstood term.

For an official to be truly “accountable” for the results of a defense acquisition, no other official outside the direct chain of command can alter or override that official’s decision, nor must the accountable official have to seek permission for any part of the program to someone not in his direct chain of command. The second key concept is oversight.

Oversight is the ability of an official or organization to be fully informed on an activity and have the opportunity to provide meaningful feedback to all the accountable decision-makers. Oversight does not mean an organization gets to make a decision, it means it gets to express an opinion. Our proposal provides for two accountable actors, each operating within its own sphere. First, the Congress, which is accountable to the American people, and then the service secretaries, who are accountable to the secretary of Defense (SECDEF) and the president.

Given the organization of the DOD and the constitutional relationship between the Congress and the executive branch, how can we align and integrate the different acquisition processes while preserving the checks and balances that limit abuse and are inherent to our form of government? First, define a new category of defense programs. These should be the truly critical programs, in terms of the dollar value, the capabilities they are designed to deliver, and the degree to which the capabilities acquired are delivered to an individual military department. The current Acquisition Categories (ACATs) are a useful starting point; most ACAT 1 programs would fit this definition. These programs would be subject to a new, unified acquisition process with the service secretary as the accountable official within the DOD. This would necessarily diminish the role of the OSD staff, and could potentially rekindle historic problems with the services being pressured into making overly optimistic decisions about their investments; however, the oversight provisions described below are designed to address that tendency.

Unifying Authority

At the start of development of a new system (roughly corresponding to Milestone B in the current DOD 5000) and at the start of production (corresponding to Milestone C in the current DOD 5000) the service secretary would approve the program requirements and test and evaluation plan generated by the service chief, the acquisition strategy generated by the service acquisition executive, and the budget generated by the service comptroller. Three DOD organizations outside the services would engage in oversight of the service’s actions.

First, the Joint Staff would have a set time to review the service chief’s capability requirement and provide a written opinion to the service secretary, SECDEF, and the Defense committees of Congress. This would allow the Joint Staff to clarify the COCOM requirements while vesting in the service secretaries the authority to balance those requirements with cost, schedule, industrial base, and life cycle support concerns.

Second, the Director of Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation (CAPE), within the OSD, would have a set time to review the service comptroller’s budget and provide a written opinion of its realism to the service secretary, SECDEF, and the Defense committees of Congress. This would give the SECEF and decision makers in Congress an independent assessment of the service’s ability to fund the program.

Finally, OSD’s Director of Test and Evaluation (DOT&E) would have a set time to review the service’s plan for the test and evaluation of the system and provide a written opinion of its adequacy to the service secretary, SECDEF, and the Defense committees of Congress. This would ensure the SECDEF and Congress understand and could act on any potential shortfalls in testing. However, in all cases, unless specifically overridden by SECDEF, the service secretary would have the final say on all the program requirements, testing, acquisition, and budget documentation that goes to Congress.

This gives the president, SECDEF, and the Congress a fully accountable official for program performance. For the acquisition of capabilities that will be operated by multiple services, SECDEF would normally designate a lead service, whose secretary would have the same authority and accountability for that capability as the rest of the acquisitions in his or her service. Some rare and complex joint capabilities may require a special DOD organization to manage across the services, such as MDA or the F-35 Joint Program Executive Office, in those cases SECDEF would designate the appropriate senior DOD official to act in the capacity of service secretary.

Just as the service secretaries are accountable, so too Congress is accountable to the American people. It is Congress, through the authorization and appropriation laws, which provides the ultimate approval for defense programs to exist. Just as the DOD must alter its internal policies to streamline acquisition, so too Congress must make changes to enable this efficiency. In addition to policy legislation to assign the appropriate roles to the service secretaries, the Joint Staff, and OSD, Congress should change how funds appropriated for the development of major defense systems are requested and expended.

Currently, there exists an appropriation category called “Research, Development, Test and Evaluation” (RDT&E). RDT&E funds expire two years after Congress appropriates them, however, both Congress and the DOD plan and track the funds as annual expenditures. In the case of both basic research and in product testing, this makes some sense. However, incremental funding of development, the process of taking extant technology and preparing it for efficient production, is almost always harmed by yearly funding. For example, the procurement of systems is fully funded (i.e., all the money required to procure a given quantity is budgeted and appropriated in a single fiscal year) with the funds lasting between three and five years, depending on product type. Development is much closer to procurement than research, and should be handled accordingly.

Also, funding development with shorter-term appropriation creates a negative incentive for DOD program managers (PMs) to spend money quickly, if not wisely, during development. Defense contractors, knowing that PMs will want to spend funds before they expire, can gain advantage by prolonging negotiations during development. In the long term, industry will also benefit from a more stable appropriation for development. The rush to place people onto a project in order to achieve desired spend rates of RDT&E creates inefficiency. With longer term development funding, industry will be better able to stabilize it workforce.

Congressional Actions

To correct this defect, Congress should create a new defense appropriation specifically for system development. When a Service requests development funds, it would present all the Service Secretary’s requirement, test, cost, and acquisition plans, along with the opinions rendered by the Joint Staff, CAPE and DOT&Es. The Service would request fully funded development for the next 3-5 years, with the exact duration of appropriation dependent on the system in question and set by the appropriations act that provides the funds. Very long developments would require a new request every 3-5 years.

To correct this defect, Congress should create a new defense appropriation specifically for system development. When a Service requests development funds, it would present all the Service Secretary’s requirement, test, cost, and acquisition plans, along with the opinions rendered by the Joint Staff, CAPE and DOT&Es. The Service would request fully funded development for the next 3-5 years, with the exact duration of appropriation dependent on the system in question and set by the appropriations act that provides the funds. Very long developments would require a new request every 3-5 years.

In order for Congress to make fully informed decisions on these procurement requests, there will have to be improved oversight and analysis by the agencies under Congress that examine the DOD. Currently, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) is the primary organization that provides Congress with independent analysis and information on which they may base their policy decisions. GAO’s oversight of defense acquisition currently falls under the Managing Director for Acquisition and Sourcing Management.

Given the complexity and volume of DOD provided information a streamlined acquisition system would produce for Congressional consideration, Congress should create a branch of the GAO with specially qualified personnel to provide meaningful independent analysis. Congress should create an Assistant Comptroller General (ACG[DA]) for Defense Acquisition, reporting directly to the Comptroller General (CG). Similar to the CG, the ACG(DA) would be a presidential appointee, ideally picked from a list of candidates selected by the chairs and ranking members of the Defense committees. Like the CG, the ACG(DA) would serve a single fixed term, although likely much shorter than the CG’s 15-year tenure.

The ACG(DA) would also be required to be a former flag or general officer, or member of the Senior Executive Service, who had served as either a major program manager, direct reporting program manager, or program executive officer within DOD. The AGC(DA)’s team of senior investigators and analysts would be made up of former DOD employees, either military or civilian, who had served as program managers or deputy program managers for major defense programs. This would ensure Congress is served by a team of professionals who were experienced in balancing risk and evaluating the decision making process with the DOD. While these acquisition experts will be in charge of Congress’ review, they will be able to draw upon the assistance of the existing GAO talent base, which has expertise in audit and review of government activity.

Also, there should be a special ability for the AGC(DA) to convene outside experts from the defense industry to aid in the review. For especially complex and/or expensive programs a team of retired senior leaders with relevant private sector leaders could provide valuable insight to this process. This arm of GAO would conduct a program review every time a service made a request for development funding in the president’s budget and at the first request for procurement funds for a program. This would provide the Congress the required analysis to make an independent policy judgment on authorizing and appropriating major defense programs.

The Role of the Combatant Commanders

The above recommendations create accountable officials and align the three acquisition processes under a single responsible official, the service secretary. However, as noted before, in war, the enemy gets a vote. A process that is based on a service secretary’s determinations and special congressional review will work for long term investments but will not be able to be responsive to dynamic conditions in an operational theater. Therefore, a second process, tied to the COCOM’s shorter-term needs, is needed as a partner to the main process. The COCOMs, or perhaps the Joint Staff representing the COCOMs, should receive a budgeted set of short term funding, similar to the current RDT&E account, to direct and fund the services for specific near term COCOM needs. In budget parlance, some portion of the services’ “6.3” and “6.4” RDT&E funding would be made available to address the exclusive needs of the COCOMs. The COCOMs would then task and fund the services for the shorter term investments needed to respond to a changing world.

This process would necessarily be much shorter than major defense procurements. The funding COCOM and executing service would agree on a scope of work, a timeline, and a level of funding. The service would then execute the work under its own processes. This would be documented in a yearly report to Congress on how the funds were executed and the AGC(DA) would conduct reviews on a representative sample of the short term work so Congress could ensure the funds were executed appropriately.

These suggested reforms are not magic, but do describe a process that will make it easier to make good decisions and provide the transparency necessary to maintain faith with the American people and their representatives in Congress.

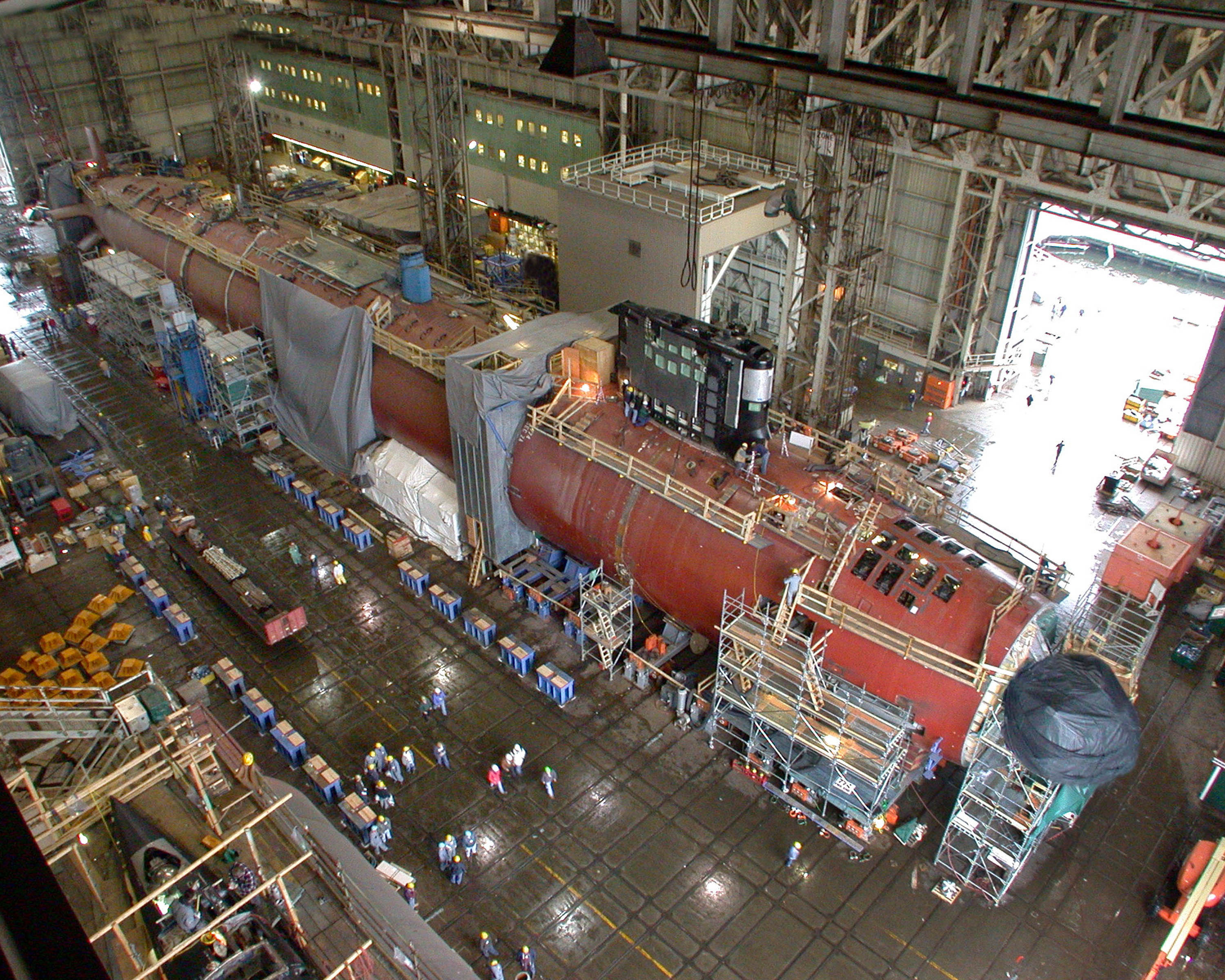

An excellent example of why the above reforms are needed was provided in the 1 October 2015 Senate Armed Services Committee (SASC) hearing on the Navy’s Ford-class aircraft carriers (CVN-78). While a healthy debate among defense minded intellectuals exists on the future utility of aircraft carriers, the administration officials testifying and a large bi-partisan majority of SASC members agreed both that aircraft carriers are vital to America’s national defense and the Navy needs the capability improvements fielding on the Ford-class to carry out its missions. Both the administration and the SASC members were clearly frustrated at the current estimated cost of the Ford-class ships.

An excellent example of why the above reforms are needed was provided in the 1 October 2015 Senate Armed Services Committee (SASC) hearing on the Navy’s Ford-class aircraft carriers (CVN-78). While a healthy debate among defense minded intellectuals exists on the future utility of aircraft carriers, the administration officials testifying and a large bi-partisan majority of SASC members agreed both that aircraft carriers are vital to America’s national defense and the Navy needs the capability improvements fielding on the Ford-class to carry out its missions. Both the administration and the SASC members were clearly frustrated at the current estimated cost of the Ford-class ships.

The hearing was an attempt to understand the roots causes of the current costs and the structure of the decision making in this program. The history of this procurement, dating back to the late 1990s, was fascinating, and included major disagreements during early program development. In one key example, the Navy, the Joint Staff, and the secretary of Defense, had a significant disagreement on how quickly new technologies should be fielded. There was a substantial policy difference over attempting to implement all the major changes on the first Ford class or to spread the improvements over two or three ships to reduce risk. Like any decision, there were clear pros and cons for either path.

What the SASC hearing highlighted was a lack of accountability and effective oversight at key points as this decision was made. Even if one accepts that the DOD might have to engage in a high-risk acquisition from time to time and that in this case the SECDEF was supportive of the higher risk option, there needed to be a better way for that high-risk decision to be communicated and evaluated by the Congress. Had a system such as the one this article posits been in place during the early 2000s, there would have been clear decisions by the Navy secretary as to how and why to proceed. Key Joint Staff and OSD organizations would have made independent assessments for SECDEF’s and Congress’ review. If SECDEF had decided to direct a different course of action, that decision would have been made more explicitly. Finally, Congress would have had both the documentation and the right team of expert advisors on hand to help them make their independent policy decisions.

Better Process, Better Decisions

Today, with decisions made in series, it takes at least three good decisions—requirements, funding, and acquisition—to get a program right. Even if the three different decision makers only make bad decisions 10 percent of the time, the chance of one of them getting it wrong and damaging a good program is about 27 percent, just over one in four. Give an accountable official the chance to get it right all at once; the DOD’s odds get better, and a higher percentage of effective defense programs will lead to a safer nation at lower cost to the taxpayer.

A final element of the success of these reforms once again resides in the Congress, specifically within the Senate Armed Services Committee (SASC). These reforms increase the authority, responsibility, and accountability of the service secretaries, which levies upon the SASC an obligation to carefully exercise its constitutional duty to vet and confirm executive branch appointees. It would be incumbent upon Congress to ensure service secretary nominees possess the capacity to exercise the increased responsibilities of the office by virtue of their previous experience in government or industry. A coherent process with competent decision-makers will go a long way toward creating an acquisition system consistent with a new era of American seapower.