SAN DIEGO – With a trio of public informational meetings this week in San Diego and Hawaii, the Navy embarked on a familiar trek: Get federal approval to keep using sonar and explosives, along with conducting other fleet training and operations, in two key training regions off Hawaii and Southern California.

The tempo of training, testing and operations in the ranges has increased in recent years, and that isn’t expected to wane with the Navy and military’s increasing presence in the Pacific.

So the Navy wants federal authority to continue to use those crucial ranges for another five-year period starting in 2018. The Navy is required under the National Environmental Policy Act to complete an environmental impact statement, or EIS, that includes detailed information and analysis of impacts from proposed action and reasonable alternatives, including “no action.”

The voluminous document analyzes impacts from military activity on the environment including marine species and water quality. An EIS is required before the National Marine Fisheries Service issues permits and grants another authority to use the ranges known collectively as the Hawaii-Southern California Training and Testing study area, or HSTT.

“The Navy proposes to conduct training and testing activities within the HSTT Study Area, including activities that involve the use of active sonar and explosives. Training sailors and testing systems are necessary to achieve and maintain military readiness,” officials said in a summary of proposed actions and alternatives. “Proposed activities are similar to the types of activities that have been occurring in the HSTT Study Area for decades and are generally consistent with those analyzed in the HSTT EIS/OEIS, completed in 2013, and earlier environmental planning documents.” The Navy also plans to refurbish existing undersea instrumented ranges.

The existing EIS expires in December 2018.

But several environmental conservation groups, including the Natural Resources Defense Council, last year sued the Navy and NMFS. In papers filed in federal court in Honolulu, they argued the Navy’s activity harmed many more marine mammals and they challenged the legality of the 2013 EIS and subsequent record-of-decision.

The court largely agreed. In a March 31 ruling, Chief District Judge Susan Oki Mollway called “troubling” and “stunning” the number of endangered or threatened marine mammals that would be harmed by training or operations.

Then, in an unusual move, the Navy and NMFS on 11 September agreed to a settlement that imposes restrictions and limitations on military training and on ship transits in areas off Hawaii and California that are known to support seasonal breeding and feeding habitats.

Among its stipulations, the Navy agrees to have surface vessels operating within the HSTT avoid approaching marine mammals head-on, and vessels must move to keep a 500-yard separation or mitigation zone if they spot whales and 200-yard zone for other marine mammals they spot, with the exception of bow-riding dolphins, when it’s safe to do so. The Navy agreed to limit use of mid-frequency active sonar (MFAS) in major training exercises including next year’s multinational Rim of the Pacific exercise and the 2018 RIMPAC and other unit-level training. Other provisions impose “extreme caution and safe speed”—largely to avoid collisions with marine mammals—and limit or prohibit using in-water explosives in various areas.

The court-approved agreement is in effect until late 2018. It remains to be seen whether the Navy ultimately adopts or incorporates those restrictions into the new 2018 EIS.

“It’s something that the current EIS . . . process will study,” said Alex Stone, the Pacific Fleet’s environmental program manager, in a KPBS-San Diego interview on Wednesday.

“It’s something that the current EIS . . . process will study,” said Alex Stone, the Pacific Fleet’s environmental program manager, in a KPBS-San Diego interview on Wednesday.

Zak Smith, a senior attorney with NRDC’s Marine Mammal Protection Project, hopes it does. “I think there’s a real interest in the Navy . . . with not having these continual battles with the environmental community over these issues,” Smith said. “And from the settlement, they are still continuing to meet all of their training and testing.”

The agreement is timely and important, he said, noting “the Navy’s own modeling showed impacts on marine mammals, so anything we can do to lessen the harm” will help the species. The settlement, he added, may show more willingness to accept that naval operations and environmental protection can be supported without hurting military readiness.

The settlement is telling, in that environmental groups previously had sought the establishment of safety, or no-go, zones where sonar use or other naval activity would be prohibited, particularly in areas or during seasons of critical marine mammal mating or breeding.

“They will definitely have to address the operations of these current mitigation” measures in the 2018 report,” Smith said. But to what degree “is a big question.”

Conservation groups are concerned that high-intensity sound waves from sonar as well as underwater explosives threaten marine mammals and can impact or disrupt marine activity. That includes the endangered blue whale and the deep-diving beaked whales that are found off southern California and Hawaii. “If you look at the Pacific Ocean, Hawaii is kind of an oasis,” Smith said.

Sonar from Navy ships training in the area is suspected in the deaths of two California bottlenose dolphins that washed up on a San Diego beach in October. But Stone said the cause of those deaths isn’t yet determined and the NMFS continues to investigate. “No one has ruled out” sonar or even a virus as causing such strandings, Smith said, but he had no other details.

Navy officials say mitigation programs, such as trained lookouts and powering-down sonar near spotted mammals, help protect marine mammals and reduce the harm from sonar use, detonations and other activities. They also note threats to marine species from non-naval sources including commercial shipping and underwater drilling.

The Navy continues to do research and monitoring of marine mammals, often working or supporting with researchers and other experts. Lt. Cmdr. Matt Knight, a Pacific Fleet spokesman, said additional information about the Navy’s monitoring programs are also available online.

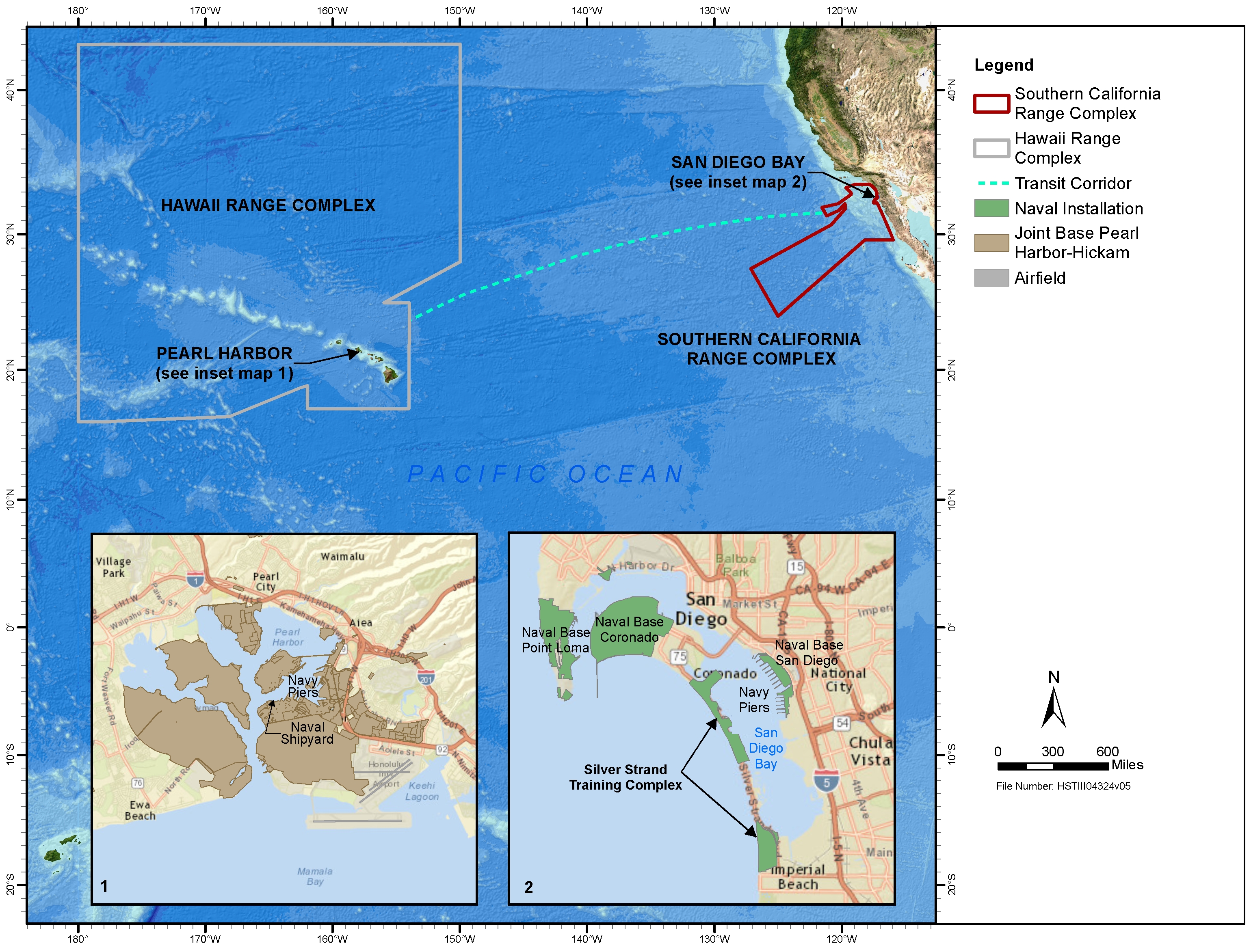

The EIS study incorporates several areas that support training and operations for the Pacific Fleet: The Southern California Range Complex, covering 120,000 square nautical miles; Hawaii Range Complex (2.7 million square nautical miles); Silver Strand Training Complex, between San Diego Bay and the Pacific Ocean; pier-side locations in Southern California including San Diego Naval Base and in Hawaii including Pearl Harbor Naval Base; and the transit corridor between Southern California and Hawaii. Of the 39 marine mammals known to be in the HSST area, eight are listed as endangered and one is listed as threatened according to the Endangered Species Act.

Additional public information meetings are being held today (3 December) in Lihue, Hawaii, and in Honolulu on 5 December. Locations, along with information about the Navy’s proposed activities, EIS process and mitigation measures, can be found at the Navy’s website.

The deadline for public comments on the Navy’s plan must be submitted online or by mail by 12 January 2016. A draft of the EIS is expected to be completed in the spring of 2017. Public comments and any updates to the report will be incorporated in the final EIS in the summer of 2018 before the Navy issues its final say in the record of decision.