In 1954, U.S. Representative W. Sterling Cole, chairman of the Joint Atomic Energy Committee, announced what had been suspected: that the U.S. Air Force could deliver an H-bomb anywhere in the world. Hardly a revelation, this boast since has been echoed for more than half a century. Indeed, Air Force talking points regularly repeat a version of this theme: We can hold any target at risk anywhere in the world in any time, any place. This idea is deeply embedded in the Air Force’s transformation efforts, as an aspirational statement became a “requirement” and thereby a justification for airpower capabilities. “Any target, any time, any place” is a centerpiece of service dogma, offered in place of coherent airpower strategy. Unfortunately, that means very little for the nation’s air, space and cyber power entrusted to the Air Force. A capability is not a strategy, and can’t be substituted for one. It’s strategy that matters.

The Target-Centric View

Airpower theorists have long since adopted a target-centric view of the world. Where Marine Corps ethos revolved around storming a beach and the Army’s about taking that hill, the Air Force viewed itself as above conventional considerations of geography and able to carry the war to the enemy. That led to a quite reasonable focus on establishing what would be targeted with airpower. That was easy at the tactical level—other aircraft, U-boats, ships, air defenses and tanks evolved as airpower’s natural prey. It was harder at the operational level—what do you have to do to affect Germany’s production of ball bearings—and much harder at the strategic level—what do you have to do to win the war? That posed a particular problem for airpower, as it had for seapower before it, because neither could take and hold land. If you couldn’t pull the rug out from an adversary by physically seizing territory, what effect might you have?

The answer was obvious. With airpower a nation could kill people and break things without having to fight through opposing ground forces. In the aftermath of World War I, where “trench warfare” in Europe was a polite euphemism for “shoveling an entire generation into the furnace,” landpower was widely, and correctly, viewed as a blunt instrument. Airpower offered an alternative. Unfortunately, the alternative offered at the time was another blunt instrument. In Command of the Air, Giulio Douhet envisioned an unconstrained battlefield, in which there will be “no distinction any longer between soldiers and civilians.” The grandfather of airpower theory advocated the mass slaughter of civilians; to him the only reason that civilians were noncombatants was that artillery could not reach them. Airpower could, and by reaching them render their noncombatant status irrelevant.

Bombing objectives should be large—small targets were deemed unimportant because Douhet intended that airpower deliver high explosives, incendiaries and poison gas against concentrations of industry, transport, and the population. In World War II, Britain’s Air Marshal Arthur “Bomber” Harris conducted the British portion of the strategic bombing effort in accordance with Douhet’s theory—minus the poison gas—focusing heavily on night bombing of German cities. One city-sized target was as good as another, and the objective was not the enemy’s capability to fight, but its will.

The Strategy Focus

The Army Air Forces had different ideas. Airpower need not be a club when it could be a blade. The Norden bombsight, which was coupled to the autopilot, was the first mass-produced, constantly-computing bomb-aiming device installed on an aircraft. The Norden Company popularized the ability to drop a bomb in a pickle barrel from 20,000 feet, an accomplishment that had a vanishingly small chance of occurrence. However, the system was still the most accurate high altitude bombsight ever, and was enough to attempt to put into practice the strategic bombing theories of the Air Corps Tactical School (ACTS). The ACTS vision of airpower employment involved disrupting the adversary’s major industrial and economic systems in an attempt to affect both the capability and will to fight. The vision was heavily dependent on a proper, scientific target analysis to determine the vulnerable points of the systems required for electrical power, transportation, fuel, food distribution and steel manufacturing. The concept was written into the Air War Plans Division—Plan I (AWPD-1). The match between targets and specific military objectives was made. Airpower would be used strategically to disrupt the manufacture and transport of combat power before it ever made it to the battlefield. It helped that the targets, factories, refineries, railroad yards and the like, were large enough to be successfully attacked and vulnerable to air-delivered weapons.

The results in World War II were extensively researched and documented afterward. The RAF’s approach was determined to be largely ineffective, while the American strategic bombing campaigns in Europe and the Pacific had measurable effects, if not independently decisive ones. In both theaters, air attacks on basic components of the economy was effective, but not perfect. The US Strategic Bombing Survey (European Theater) (USSBS-E) said as much: “In the field of strategic intelligence, there was an important need for further and more accurate information, especially before and during the early phases of the war. The information on the German economy available to the United States Air Forces at the outset of the war was inadequate. And there was no established machinery for coordination between military and other governmental and private organizations.” The obvious problem with intelligence was that it was not and could not be perfect and that the completeness and accuracy of intelligence was the key factor that affected the design of a strategic bombing campaign. The same postwar observation was made by the Strategic Bombing Survey (Pacific Theater), where relentless air attack, including aerial mine-laying, bedeviled the Japanese from 1942 onward. “In the final assault on the Japanese home islands we were handicapped by a lack of prewar economic intelligence. Greater economy of effort could have been attained, and much duplicative effort avoided, by extending and accelerating the strangulation of the Japanese economy already taking place as a result of prior attacks on shipping. This could have been done by an earlier commencement of the aerial mining program, concentration of carrier plane attacks in the last months of the war on Japan’s remaining merchant shipping rather than on her already immobilized Warships, and a coordinated B-29 and carrier attack on Japan’s vulnerable railroad system beginning in April 1945.”

The strategic air campaigns were successful despite an incomplete knowledge of the target sets because the concept was correct. The desired effect was to disrupt German and Japanese war production, which was achieved in good measure. True, it could have been done more efficiently, but the effectiveness was not in question. In the Pacific, conventional land and carrier-based airpower employment may have involved more than a little overkill, because we could not precisely divine the effects of attacks on industry and maritime traffic. “We underestimated the ability of our air attack on Japan’s home islands, coupled as it was with blockade and previous military defeats, to achieve unconditional surrender without invasion. By July 1945, the weight of our air attack had as yet reached only a fraction of its planned proportion, Japan’s industrial potential had been fatally reduced, her civilian population had lost its confidence in victory and was approaching the limit of its endurance, and her leaders, convinced of the inevitability of defeat, were preparing to accept surrender” (USSBS-P). From the standpoint of an interdiction campaign, the eventual bombing of the home islands was enabled because of the steady march of Navy, Marine and Army Air Forces aviation capabilities across the theater, combined with the devastation of maritime transport by the Pacific Fleet’s submarines.

Strategic bombing took a break during Korea (interdiction absorbed the majority of air to ground efforts) because the real strategic targets were in China and the Soviet Union, both off limits. Similarly, in Vietnam, years of airpower employment in Rolling Thunder were wasted because the strategy was constrained and the targets did not matter—if we could not execute a strategy against industry and transportation in North Vietnam, no amount of targets south of the DMZ would change the strategic balance. When the gloves came off in Linebacker II, eleven days of bombing shattered North Vietnamese transportation, industry and supply depots, reinforcing the maritime cutoff achieved by the Navy’s mining of North Vietnamese ports seven months earlier. A peace agreement followed less than a month later. Matching a tried and true airpower application with the strategy that enabled key industrial and transportation elements to be attacked achieved success where years of “target-centric” employment had failed.

The Precision ‘Revolution’ and the Five Rings

Vietnam introduced the first use of precision munitions against ground targets. Shrike, Standard, Bullpup, Paveway and HOBOS systems were all utilized with substantial success. For the first time, it was possible to allocate one weapon against one target with a predictable result. That potential had both strategic and tactical implications, and was an obvious answer to the massed Soviet threat in Europe. In the late 1980s, the post-Vietnam force construct was matched with a new wrinkle in airpower theory. Col John Warden III published The Air Campaign: Planning for Combat in 1988, providing a concise, believable and well-constructed planning guide for air operations. It returned in part to classic Douhet in asserting that airpower could win wars, but added the key wrinkle that the true center of gravity for air attack was the command element, which could be attacked via three routes: “the information sphere; the decision sphere; and the communications sphere.” This was a radical departure from ACTS views. Careful reading revealed that Warden himself conceded that successful targeting of the command element would be difficult to determine afterward—at least for a while.

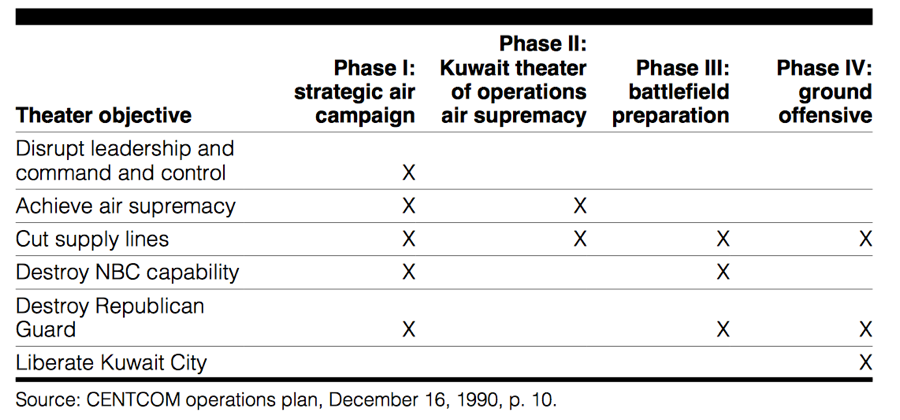

Desert Storm offered the first opportunity to test the capability of precision weapons on a large scale and was an unambiguous success for airpower. The General Accounting Office’s air campaign analysis noted that even though 92 percent of the munitions employed were nonprecision weapons, they were employed in a manner suitable for their capability. Precision weapons allowed attack against targets that were small or that required very precise weapons placement to achieve the desired effect. Had more aircraft been equipped with the capability to guide precision weapons, more would certainly have been used. An early air campaign plan, dubbed Instant Thunder, was designed by Col. Warden and the Checkmate (the Air Staff’s Planning Cell in the Pentagon) as a decapitation plan with 84 targets. Deemed insufficient by Lt. Gen. Chuck Horner, it was taken out of Checkmate’s hands and expanded significantly before execution. The success of the air campaign was widely believed to have provided validation of Warden’s theories—but in retrospect it was also a validation of the value of realistic training, discipline, overwhelming logistics, sheer mass of firepower and the ability to almost completely surround an adversary and attack on a timeline of one’s choosing. As brilliantly as the air campaign was executed, we held every advantage, had a very well-developed, airpower-centric strategy, and we faced a startlingly inept adversary. The campaign plan remained focused on specific, sequential operational objectives and not specific targets. It was not a decapitation plan so much as an interdiction plan—the heart of AirLand Battle doctrine developed for a conflict in Europe.

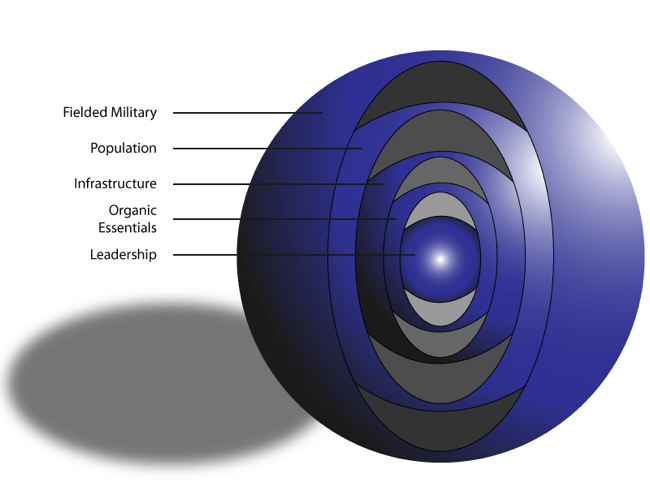

The success of Desert Storm had three very unfortunate consequences. First, it inculcated a “short war” mentality that led to advocacy of any method that promised a short war, regardless of the actual potential for success. Second, it allowed airpower advocates to focus on the weapons, the targets and the delivery platforms, while relegating a flexible strategy to the back benches. Finally, it encouraged a mistaken belief in strategic paralysis and decapitation attacks, neither of which occurred. The decapitation plan received entirely too much credit, especially for a plan that had been rejected, and is widely and mistakenly believed to have been the center of a much broader strategy for the effective employment of airpower. After the war, Warden published The Enemy as a System, which forever sealed his position as an airpower theorist and expanded on the now-canonical “five rings” model of an enemy system.

In the article, which was (and is) widely read, Warden doubled down on the importance of the center “leadership” ring, which he defined as the “most critical ring.” “It is imperative to remember that all actions are aimed against the mind of the enemy command or against the enemy system as a whole. Thus, an attack against industry or infrastructure is not primarily conducted because of the effect it might or might not have on fielded forces.” This turned ACTS theory around and focused on the will and capability of the command element, where previous strategies focused on the will of the command element but the capability of the fielded forces. Warden also tied an air campaign strategy to the idea of “strategic paralysis” and parallel attacks against a limited target set. “States have a small number of vital targets at the strategic level-in the neighborhood of a few hundred with an average of perhaps 10 aimpoints per vital target.”

Airpower theory had come full circle. In effect, Warden argued for a return to a Douhetian model, with precision attack taking the place of mass attack, against a limited number of strategic targets. The theory readily adapted itself to a discussion of “targets” because the strategy espoused was the destruction of the small number of “first ring” targets. Airpower enabled a theoretical simultaneous attack against all of these targets, thus delivering the holy grail of airpower theorists—the decisive strike which disables the enemy’s ability to fight. The model was a valuable way of looking at a target country. As a campaign plan it was flawed from the outset. Warden was openly contemptuous of the effects of fog and friction, believing that those elements were relegated to history. He also vastly overestimated the ability of any force to effectively predict the effects of its actions. The article vastly underestimated the number of “vital targets” in a modern industrial state. Most important, the article became mistakenly associated with Desert Storm in the minds of airmen everywhere. And it moved airpower theory into a target-centric philosophy from which it has not recovered.

The Nimble Lion Plan – Return to Rolling Thunder

The next real test for airpower theoreticians was Allied Force, the air campaign against Serbia. In 1995, Deliberate Force had brought the Serbs to the bargaining table over Bosnia in only three weeks of air attack. Airpower may have accelerated a process that was under way already or it may have changed the strategic calculus of the Republika Srpska. The Balkans Air Campaign Study got it exactly right when it placed the campaign plan as one of several strategic tools. “Deliberate Force was a decisive element in shaping the outcome of the allied intervention into the Bosnian conflict, but its full effect must be understood in the context of the other political and military developments also under way at the time”.

The Dayton Peace Accords in no way ended fighting in the Balkans, and Serbian offenses against Kosovar Albanians persisted. In NATO’s Air War for Kosovo, RAND reconstructed the planning timeline. By June of 1998 planning for the next air campaign began. Called Nimble Lion, it was designed to bring the Serbian president to the peace table and end his depredations in Kosovo. The plan was a Linebacker-style air offensive that entailed a heavy weight of effort from Day One. It was rejected in favor of Conplan 10601, a Rolling Thunder-style campaign of incremental pressure. The same problems that bedeviled incrementalism in Vietnam arose—it was impossible to adequately determine which effects from an incremental campaign would bear fruit. The first phase of the “air campaign” was not in fact an air campaign. It was a plan to service 51 air defense targets and another 40 disposable military targets such as barracks, headquarters and airfields. Planning for airpower employment had devolved to the point where the target set was limited to targets that were not so destructive that NATO members could not agree to strike them.

NATO airpower exhausted the target list in 72 hours. Day four opened with NATO aircraft hitting targets with no significant military value for no appreciable effect. USAF aircrews at Aviano AB recognized the transition from a bad plan to no plan at all, and were widely disappointed that they were bombing “suspected truck parks in the jungle”—a deliberate historical reference to Vietnam. While the target list was expanded soon after, NATO never got back on stride with a coherent air campaign plan and resorted to casual airpower vandalism on a grand scale, hitting bridges, fuel storage, tunnels, airfields, factories and the sole oil refinery. By week six aircrews were hunting for “tanks under trees” in Kosovo and restriking previously approved targets, a process referred to as “turning bricks into rubble.” In the end we arrived at a dubious victory through a means we did not then understand. Devoid of a coherent strategy, Allied Force was a grand experiment in using precision airpower as a blunt instrument to force concessions from an enemy who could not effectively resist. Ironically, Douhet had been validated by the lack of an air campaign plan.

The Strategy Conundrum

In Allied Force, airpower partisans had unambiguous “proof” that airpower could win a war, even if they had no evidence that the experience was repeatable. We even had a template for doing it—a template that involved precision attacks against strategic targets using stealthy aircraft, which were viewed as being effectively invisible. True, the F-117 had slipped through Iraqi air defenses with impunity, but the Serbs, using the same air defense systems as the Iraqis, managed to bag an F-117 eight years later. Similarly, the Electronic Combat triad of F-4G, EF-111A and EC-130 was dismantled in favor of stealth and the new belief that the USAF could neutralize adversary air defenses in 72 hours, regardless. After all, it had been done, once. The inability to completely neutralize Serbian air defenses was somehow an aberration while the success of the air effort was not. All we had to do was service the correct targets.

The air campaign against Afghanistan did not further advance an argument for strategic airpower one way or another—Afghanistan was not an industrialized nation and air power. Massively successful when paired with special operations, air power was essentially used tactically to defeat an enemy who could not have been attacked strategically. Iraqi Freedom should have shattered the belief in both decapitation and strategic paralysis, since on paper, there was no adversary who was more susceptible to this kind of attack. By 2003, Iraq had been shattered for 10 years and had been the victim of a long, undeclared air campaign against its air defenses, C2 and communications starting in 1998 and growing out of reactive strikes against no-fly zone air defenses. “Shock and Awe” was going to do the trick this time. And yet, despite Iraq lying supine before Coalition airpower, the issue was not decided until ground forces rolled into the capital—and arguably not even then.

There were other prevailing winds. The 2001 Quadrennial Defense Review had shifted defense planning into “capabilities-based planning,” which separated potential adversaries by the weapon systems they possessed and inaugurated defense planning that was devoid of warfighting strategy—replacing it with acquisition strategy. Attempts were made to counter this trend, particularly with an emerging school of “effects-based operations,” which argues that the value of destroying a target is determined entirely by the effects that occur as a result—an intuitively obvious assertion that was being lost in the application of the approved template. The elephant in the room remains, as always, the ability to characterize an adversary to the degree necessary to determine what effects we wish to garner using which method. Once again, there existed a fundamental necessity to determine “targets that matter,” despite a century of evidence that should have demonstrated that the targets matter much less than the strategies. Nevertheless, the “one size fits all” view of airpower application holds strong sway.

The Air Force, in particular, seems to have been captured by a target-centric view of the world, although it is not entirely clear that naval aviation has not also been captured by the same illusion. The Desert Storm recipe for airpower success has been misappropriated; what should have been an argument for a flexible, adaptive strategy based on detailed understanding of a specific adversary in a specific environment has instead become something much less. If the United States is to remain the preeminent practitioner of airpower, it has to return to both a grasp of strategy and the ability to craft an effective air campaign plan against adversaries that do not look or act like 1991 Iraq. We have to understand that strategies matter in warfare, and that targets that matter—don’t.

Next Week: Strategies That Matter Part II: One Size Fits None