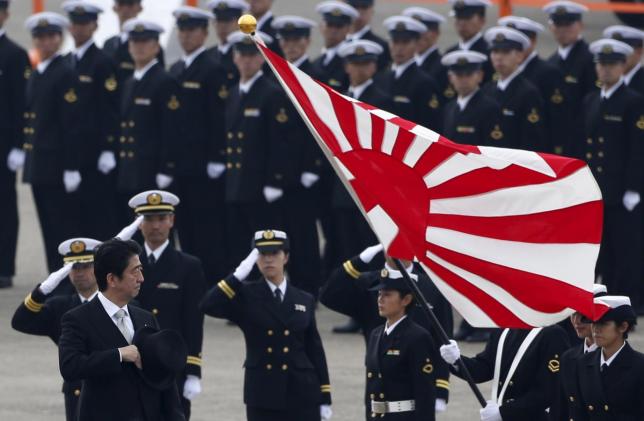

The government of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has proposed major changes in Japan’s defense policy, with strong implications for the United States and U.S. armed forces in the Pacific. The changes, designed to shift Japan away from an isolated, pacifistic defense posture to a more dynamic one based on bilateral and even multilateral relationships, are controversial but not uncommon to most nations.

Politically, Abe’s security agenda is designed to get Japan more involved in the world, and more capable of being a partner operating with the United States. Japan’s de facto military, the Self-Defense Forces, would be able to reciprocate American efforts to defend Japan. Abe is also concentrating on increasing SDF interoperability with U.S. forces.

Policy Changes

Abe is trying to pass two security bills: the first would allow Japan to provide logistical support to countries participating in U.N. peacekeeping missions. Such support is currently forbidden under the theory that it assists participants in a conflict, with no distinction made for participating in a U.N. mission.

The second bill amends several others currently on the books, and most important, would legitimize the concept of collective self defense. The concept of collective self defense, the right of Japan to come to the aid of other countries that are under attack, is guaranteed under Article 51 of the U.N. Charter. Regardless, it is forbidden under the current interpretation of Japan’s constitution.

The subject of collective self defense has long been a cornerstone of Abe’s political beliefs but assumed a new level of urgency in light of recent tensions with China. One Japan analyst said that privately, the Abe government doubts the United States would be willing to help Japan against China if Japan does not take on a more assertive role in the world.

Increased Defense Budget

Faced with annual increases of the Chinese defense budget of ten percent or more, Japan is eking out a modest increase of 0.8 percent annually through 2018. The defense budget request for the next fiscal year is 5.2 trillion yen, or $41.9 billion at current exchange rates. Political opposition, a sluggish economy and a national debt currently at 233 percent of GDP has prevented greater increases.

Japan has several major defense procurement programs in progress. Most of the equipment is American in origin, with an eye toward commonality and interoperability with U.S. forces in joint operations. A large portion of next year’s acquisition spending will be on the purchase of 17 SH-60 helicopters and the new maneuver combat vehicle, an 8×8 wheeled vehicle armed with a 105mm gun designed to give fire support to Japan’s rapid deployment forces.

Other large programs under way are construction of a second Izumo-class helicopter destroyer, two additional Aegis destroyers, 17 Bell-Boeing V-22 Osprey tilt-rotor aircraft, and 42 Lockheed Martin F-35A Joint Strike Fighters. Also rumored to be under development is a new amphibious vehicle to eventually replace the 52 refurbished amphibious assault vehicles purchased from the U.S. Marine Corps.

Joint Training

The U.S. military and Japan Self-Defense Forces already conduct joint operations on a monthly—sometimes weekly—basis, but the Abe administration has further deepened levels of cooperation. This summer all three arms of the Self-Defense Forces—air, land and maritime—are conducting operations with their American counterparts.

From mid to late July, Air Self-Defense Forces aircraft operated out of Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson for Red Flag 15-3. The ASDF is a regular participant in Red Flag exercises and this year sent a package of six Mitsubishi F-15J fighters, three C-130 transports, two KC-767 tankers and one Boeing E-767 AWACS aircraft.

On 12 August, paratroopers from Japan’s 1st Airborne Brigade dropped alongside their American peers from 4th Brigade, 25th Infantry Division in Exercise Arctic Aurora. The occasion marked the first time Japanese paratroopers have dropped on American soil. Also on 12 August, two SDF special forces members were injured when a U.S. Army Blackhawk helicopter made a hard landing on the USNS Red Cloud.

Later this month the Ground and Maritime Self-Defense Forces are set to participate in Exercise Dawn Blitz off the coast of California. Japan is sending the helicopter destroyer Hyuga, Aegis destroyer Ashigara, amphibious warship Kunisaki and an unknown number of GSDF amphibious troops to participate in the U.S.-led multinational exercises.

In addition to such efforts with the United States, Japan has also undertaken joint training exercises with Australia and the Philippines, and has agreements for joint training with India, Indonesia and Vietnam.

Joint Operations in the South China Sea

Although the SDF has trained for decades alongside U.S. forces, actual joint operations are unheard of. Now as part of its anti-China strategy Japan is taking a multilateral approach to pushing back on Chinese territorial claims. In doing so, Japan can leverage its limited political and military capabilities by partnering with those in a similar predicament versus China—but with fewer operating restrictions.

Japan has expressed a desire to join “Freedom of Navigation” patrols by the U.S. military in the South China Sea. Japan has also proposed joint operations with armed forces of the Philippines. Such a forward stance in South China Sea has no real downside for Japan: if it curbs Chinese expansionism, it will achieve Japan’s strategic goals. If it fails to deter China, the South China Sea was never a core interest anyway.

The deployment of Japanese ships and planes to the South China Sea would provocative. The Chinese government has declared that Japanese patrols of the South China Sea—of which it claims 90 percent as part of China — would be “unacceptable.”

Key Equipment for Interoperability

Japan’s pending purchase of equipment designed to operate with the U.S. Navy’s Cooperative Engagement Capability—a system designed to share sensor data across networks and provide targeting data to missiles—is a strong hint the the SDF intends to work even more closely with the U.S. than ever.

Two important acquisitions will aid JSDF forces in operating alongside U.S. forces. Japan is planning to purchase four Northrop Grumman E-2D Advanced Hawkeye Airborne Early Warning and Control aircraft. The $1.7 billion deal was approved by the State Department on 1 June and will be handled by NAVAIR.

Japanese E-2Ds will use their APY-9 radars to extend the detection range of Japanese and allied naval forces, detecting both aircraft and ballistic missiles at greater distances than surface ships can. Such data could, for example, be used to target ballistic missiles, cruise missiles and aircraft with SM-3 and SM-6 missiles launched from networked surface combatants.

Japan’s planned seventh and eighth Aegis destroyers, soon to start construction, will be equipped with the Cooperative Engagement Capability and Common Datalink Management Systems, aiding their ability to share air and missile threat data with U.S. ships and aircraft. CEC will allow the Aegis destroyers to network with sensor platforms such as the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter and E-2D Advanced Hawkeye and pass the data on to other ships in the fleet, whether Japanese or American.

Public Pushback

Abe’s security reforms have been among the most controversial items on his agenda. In the wake of World War II Japanese society adopted a strongly pacifist bent, becoming strongly skeptical of military force to solve disputes. Abe’s reforms are seen by many Japanese as a rollback of what they consider Japan’s progressive peace posture and a signpost on the route to remilitarization.

Still, the lack of significant political opposition to Abe and his Liberal Democratic Party means there will be no meaningful pushback by a competing political party. The lower house of Japan’s bicameral legislature voted in favor of the security bills in early July, and the upper house must vote on the changes no later than 6 September. Even if the upper house does not pass the bills, the lower house can, and probably would override the veto.

Conclusion

The defense policy revisions currently being pushed by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe are not particularly remarkable. Although controversial in Japan, they serve only to give the country the defense capabilities the United Nations considers a right of all nations. Although public opposition to these changes is steadily increasing, they are likely to pass Japan’s legislature and become law.

In the meantime, the Self-Defense Forces are preparing to cooperate with U.S. air and naval forces on levels not seen before, with the means to seamlessly integrate with both on the battlefield. As attention shifts to the Indo-Pacific, Japan may prove to be the most valuable and potent ally the United States has.