SILVER SPRING, Md. – Eighty years ago, the Navy’s last flying aircraft carrier crashed off the coast of California and sank to the bottom of the Pacific Ocean.

The sinking of USS Macon (ZRS-5), a lighter-than-air rigid airship, resulted in few deaths but its loss ended the Navy’s quest to use airships as long-range scouts for the fleet.

While the idea died, the wreck Macon lives on as an important archaeological site and this week Naval History and Heritage Command, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and several non-profits came together to explore the wreckage, mapping out pieces of the airship and its four biplanes and studying the change in its material condition over time.

Their hope: to understand life aloft in the floating aircraft carrier, to piece together a clearer map of the wreck site and to research how quickly the remains of the airship are being consumed by the sea.

USS Macon Life and Legacy

As early as 1916 the Navy had begun designing lighter-than-air (LTA) rigid airships, and by 1926 the focus had shifted to airships that could support aerial scouting missions. The first flying aircraft carrier, USS Akron (ZRS-4), was commissioned in 1931 – and after several incidents in two years, the airship crashed and sank off the coast of New Jersey in 1933, killing 73 of 76 men onboard, including Rear Adm. William A. Moffett, the first chief of the Navy’s Bureau of Aeronautics and the chief proponent of bringing LTA aircraft to the fleet.

Macon was commissioned a month and a half after the Akron crash. The airship was commanded by one of the only Akron survivors, Lt. Cmdr. Herbert Wiley, and was based in California. The second-in-class dirigible had a slightly longer service life. The airship stayed mission-ready and participated in many fleet exercises in its two years.

Macon demonstrated its concept of operations, launching and recovering as many as five single-seat Curtiss F9C Sparrowhawk biplanes via a “trapeze” that the crew used to recover the planes. The planes often had their landing gear removed while operating from the airship, leaving little room for error for the pilots.

On Feb. 12, 1935, the airship hit a storm off the coast of Point Sur, Calif. A tailfin was sheared off, and in trying to respond the crew set off a chain of events that led to them losing control of the airship and falling nose-up into the ocean, according to a post in the Naval History Blog. The aircraft fell slowly enough that the crew could put on lifejackets – which were onboard the Akron. One crew member jumped from the airship at too high an altitude and died, and another died when he returned to the sinking ship to retrieve personal items. The other 74 crew members were rescued. However, the rigid airship program was beyond saving.

Bruce Terrell, chief archaeologist and historian at NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries’ Maritime Heritage Program, told USNI News on Tuesday that the Macon, for all it lacked in longevity, shed a lot of light on how the Navy perceived the threats to the U.S. in the Pacific.

“it’s showing the pre-World War II mindset of the Navy. And as early as the turn of the century, the Navy was focused on Japan, watching Japan, because their military was increasing so fast and they kind of were getting clues as to the Japanese government’s designs on South East Asia and the islands,” he said.

“Macon was envisioned as basically a scout for the fleet, Macon and Akron. … it kind of shows how the Navy was looking at scouting for the fleet, protecting the fleet. And Macon was kind of the highest expression of the technology, but as this was happening seaplanes with longer and longer range capability were being developed, radar was starting to be developed, newer technologies were coming along. So I think the Navy, at that point when Macon finally crashed, it was like, okay, we’re cutting our losses here. … But I think the concept was proven after Pearl Harbor – the big what-if question is, if Macon had been operational and successful, might Macon and the little scout aircraft, might they have spotted the Japanese fleet before they could hit Pearl Harbor?”

Exploration and Mapping Mission

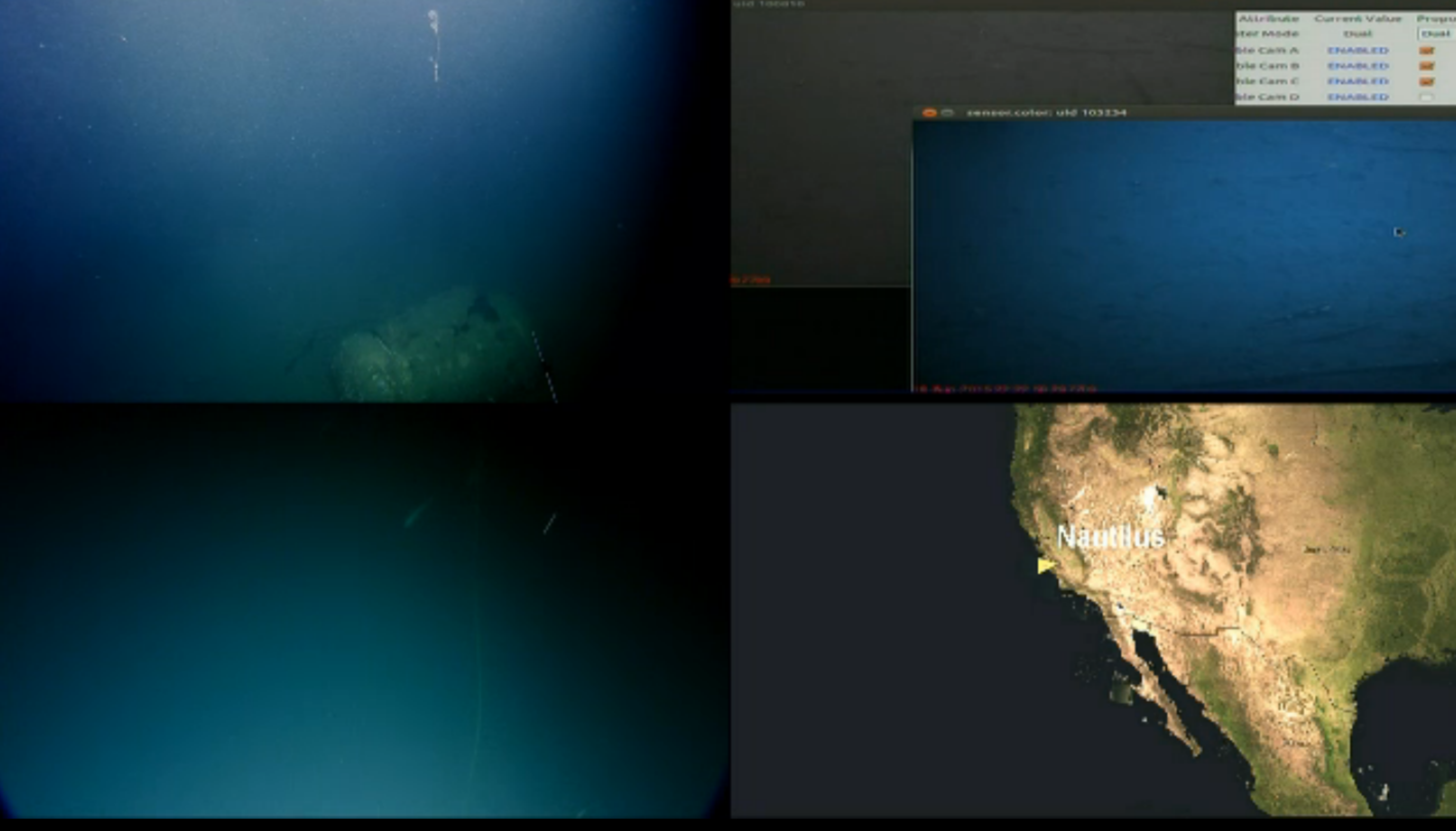

On Tuesday morning, scientists, archaeologists and other experts gathered aboard the 211-foot Exploration Vessel Nautilus at the wreckage site; at the ship’s command hub, the Inner Space Center at University of Rhode Island’s Graduate School of Oceanography; and at NOAA headquarters in Maryland.

Broadcasting the whole operation live online, the team prepared for its 12-hour mission: to find the boundary of the wreckage site, to create a photomosaic of the site, take 3D video of small portions of interest and to retrieve a small piece of aluminum for metallurgical study.

The layout of the Macon site is already fairly well understood. Explorations in 1991 and 2006 photographed and identified the bulkiest items on the ocean floor – engines, fuel tanks, ovens, tires, and the four biplanes still relatively intact, among others – and even retrieved some items for study and display.

But Terrell explained that this exploration will provide even greater detail, thanks to technological advances. New high-definition sonar will give researchers a better look at some of the smaller items, which are key to shedding light on what daily life was like aboard Macon.

“We’re already getting a better sense of how Macon wrecked and came to rest on the seabed, but I think [this exploration is] going to help us identify actual objects more. It’s just a cumulative process that’ll be going on for years,” he said.

A finer look at those items in the wreckage will help answer several questions, Terrell added.

“We want to know basically what’s there, identify objects, things like that. We want to know how it wrecked, how all that happened,” he said.

“But then we want to understand the more human story. Now with Macon, there were two losses, a radioman and a steward; we know the radioman jumped from too high and broke his back, so they may have recovered his remains. But the steward ran back into the galley and was never seen again, so we may have a military grave there. But then the other human question we want to answer is, since there were people onboard, we want to know basically how the workspaces were arranged on Macon, how this big complex ship in the sky actually operated – how they interacted with each other, how they communicated, what kind of personal effects may have been onboard. We know we’ve got a lot of the galley there, it would be interesting to know how they cooked and ate their food up there in the sky.”

To answer the questions, the team took the Ocean Exploration Trust’s Nautilus and its dual-body remotely operated vehicle system, composed of primary ROV Hercules and and secondary vehicle Argus. The pair are outfitted with lighting, cameras, sensors and sonar to document what they encounter at the bottom of the ocean.

The Nautilus crew launched the ROVs just after 8 a.m. EST, and it took the vehicles about an hour to reach the search site, more than 1400 feet below the water’s surface.

The first step was to find an accurate perimeter for the photomosaic – Terrell said the one created in 2006 did not include the full wreck site. The mission covered Field A, which is the back two thirds or so of the Macon – including the Sparrowhawks, the ovens from the galley, engines and more – and Field B, which is the smaller front section of Macon.

Hercules and Argus then “mowed the lawn” for about five and a half hours in Field A and for more than three hours for Field B, taking photos every few seconds to create the photomosaic.

The ROVs were able to take 360-degree video of a biplane, take some measurements of corroded parts of a plane wing, and measure how much sediment had built up since 1935. The last item on the mission agenda was to pick up a piece of aluminum girder to bring back and study. Terrell told USNI News on Wednesday that the first piece the ROV’s manipulator arm picked up “turned to dust” when moved. The scientists located another similar-sized piece but found that an object was obstructing access to it. Upon trying to move the piece sticking out of the ground, they found it was another piece of girder – half of which had been exposed to the water and half of which had been buried in the ocean floor and protected. Right as time expired for the mission, the scientists brought up the girder, found it fit in their protective box, and were able to call the mission a success, Terrell said.

Expedition’s Lessons Learned

For those involved in the mission, Tuesday’s expedition was part of an obligation to monitor and preserve the wreck site to the best of their ability, given the great environmental challenges associated with artifacts under 1,400 feet of saltwater. Macon and its scout planes will eventually be corroded away, and these organizations want to continue to document their condition now and into the future.

“We’re really extending the life of this airship and her biplanes and documenting the past 80 years she spent under water, which is the majority of her life,” NOAA archaeologist Megan Lickliter-Mundon said while broadcasting from Nautilus.

But she noted Tuesday afternoon that the artifacts may be corroding faster than expected. One of the biplane’s wing collapsed since the 2006 expedition, which scientists knew would happen eventually but didn’t expect so soon. Gaining a better understanding of aluminum in the Macon frame and the Sparrowhawks will help scientists predict how long the wreckage will remain intact and may inform future expeditions.

Alexis Catsambis, archaeologist and cultural resource manager at Naval History and Heritage Command, said Tuesday that the Navy has a good understanding of how materials from older shipwrecks – wood, iron, copper alloys – react to their underwater environment. But with 20th Century materials like aluminum alloys, “we haven’t quite figured out as a discipline how to best conserve the material, how those materials react with their environment and with other materials. And so this is an opportunity to learn through the sample that we collect about the rate of degradation of certain aluminum alloys and hopefully how to best help preserve them,” he said.

At the Naval History and Heritage Command, “we are charged with managing the sites, with researching the sites, with conserving and curating artifacts that are recovered from them, and ultimately public outreach,” he said, and this mission taps into each of those missions. He said the Navy hoped to retrieve a piece of aluminum from the Macon frame, perhaps one or two feet long, for testing and eventually to loan out to a museum.

Russ Matthews – whose family’s Edward E. and Marie L. Matthews Foundation helped pay for the expedition, along with the Oceangate Foundation – said Tuesday that bringing this “odd branch of aviation evolution that went nowhere” into the public discourse was important to him. He said the history of the dirigible program “reads like science fiction,” and he hopes that research teams can continue to learn more about the program and preserve and document artifacts for future generation.