While several Chinese security-scenarios are discussed in defense circles, China’s Taiwan dilemma is still the primary driver for Peoples Liberation Army (PLA) acquisition.

Resolving China’s Taiwan issue has been the PLA’s justification for double-digit budget increases over decades. The force needed to deal with a U.S. military intervention during a Taiwan contingency far outweighs that required to handle China’s other external security goals.

The Taiwan issue is reflected in the PLA Navy’s (PLAN) undersea force structure, which in recent years has heavily prioritized the construction of Type-39A Yuan-class conventional submarines (SSK). According to Naval War College professor and PLAN watcher Lyle Goldstein, the Yuan is “one of the sharpest spears in China’s maritime arsenal.”

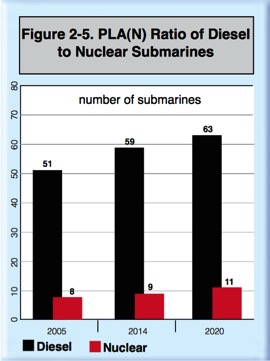

The Yuan was primarily designed to deal with U.S. forces during a Taiwan contingency and is the only SSK that China is currently producing. The recent pace of Yuan construction has been staggering. Between 2010 and 2011 the PLAN launched eight Yuans and in 2012 alone laid down five new Yuan keels. There are currently 13 Yuans in service and seven more being constructed. The PLAN may construct up to 20 more. Rep. Randy Forbes (R-Va.) recently stated “within five to eight years [The PLAN] will have about 82 submarines in the Asia Pacific area.”

A graph from the Office of Naval Intelligence’s recent report on the PLAN, shown below, anticipates China’s continued prioritization of SSKs over the next decade.

Given that submarine lifetimes run between 20-30 years, a substantial portion of this force will be Yuan-class. The Yuan will remain a key aspect of PLAN force structure through the 2030s and 2040s. If a conflict occurs between the U.S. and China around Taiwan or in the South China Sea, the Yuan will play a critical role in Chinese area-defense area-denial (A2/AD). Therefore, understanding of the Yuan’s design philosophy—what it was designed to excel at—is important for U.S. policymakers and the defense community at large.

Trade-off analysis is derived from the reality that weapons can never be everything or do everything perfectly and economically. Compromises must always be made. Understanding what capabilities the Yuan’s designers were willing or unwilling to sacrifice gives an analyst suggestive-insight into the goals and mindset of the PLAN.

A trade-off analysis on what little public information is available on the platform suggests the PLAN designed the Yuan to be a small, quiet, slow-moving anti-surface warfare platform. While the Yuan is undoubtedly capable of traditional SSK mission roles such as regional intelligence-gathering and coastal defense, trade-off analysis suggests the Yuan was designed primarily as an anti-ship cruise missile (ASCM) platform capable of hiding submerged for long periods of time in difficult-to-access shallow littorals.

Japan’s Soryu-class SSK provides an ideal contrast with the Yuan. The Soryu is 84 meters long, with a draft (height from water line) of 10.3 meters, a beam (width) of 9.1 meters, and a crew of 70. In contrast, the Yuan is 73-75 meters long, with a draft of 5.5 meters, a beam of 8.4 meters, and a crew of 58. Various sources report different submerged displacements for the Yuan. Comparatively, it is far smaller than the Soryu: The draft is 4.3 meters shorter, the length around 10 meters less, and 0.7 meters thinner in width.

Water pressure and hydrodynamic drag place a premium on submarine internal volume. Increasing an SSK’s capabilities, such as magazine (ammunition) depth, range, stealth, or speed, for example, no doubt has an upward-spiraling effect on platform size. Likewise, shrinking a submarine’s size would put substantial downward pressure on every onboard system, such as crew size, habitability, fuel storage, magazine depth, etc. Make no mistake: the Yuan’s designers accepted capability reductions in various areas in order to maintain a small size.

The Yuan’s small profile takes a new significance when compared to its non- air independent propulsion (AIP) equipped predecessor — China’s Song-class SSK. The AIP-equipped Yuan and non-AIP Song have extremely analogous dimensions.

AIP — which produces propulsion power underwater without taking oxygen from the surface — is a significant force-enhancing technology because it enables between 14 to 25 days submerged (depending on AIP-engine type and propulsion activity), thus enhancing survivability by decreasing the frequency with which the SSK needs to “snorkel” (recharge batteries using primary engines), which exposes the submarine to detection. Yet important to this analysis is the fact that AIP systems are large and take up internal volume. PLAN naval architects deliberately maintained the Song-class’s size even with the installation of an AIP system.

Pakistan’s Agosta-class SSK’s MESMA (Module d’Energie Sous-Marin Autonome) AIP system hull insertion-section is 8.6 meters long. Greece’s type214A (German-made) SSK’s 240 kW Fuel Cell system weights 1,800 kg and takes up a 1000-liter volume.

Installing a Stirling-AIP hull insertion into Sweden’s Gotland-class SSK fleet required an 8 meter hull insertion. While the Yuan’s Stirling-AIP system is non-modular (which is more efficient as it is included in the Yuan’s design ground-up, as opposed to a sectional hull-insertion, which is less space-efficient), there is no doubt that the inclusion of an AIP system required capability reductions elsewhere in order to maintain the Song’s size.

While there is a possibility that advances in automation may have contributed to the Yuan’s maintaining of the Song-class’s length, this is improbable, given the Song and the Yuan’s comparable crew sizes (60 and 65, respectively). For context, on board crew is actively minimized during submarine design so as to increase space available for other systems. Much of a submarine’s crew exist to make up for gaps in automation. Therefore given the two submarines’ probable similarity in automation technology and highly analogous dimensions, PLAN naval architects clearly placed such high value on the Yuan’s small profile that even with an AIP system the Song’s platform size was maintained. Why did the PLAN emphasize small platform size, when there are clear, immediate capability benefits to a Soryu-sized platform?

Advantages of a Small Platform: Shallow Operations

There are two advantages to small platform size: shallow operations and cost. The Yuan’s small size enables it to take fuller advantage of the shallow littorals that pepper the area around Taiwan and the South China Sea. The PLAN certainly has accurate surveys of China’s local ocean floor geography, water-temperature trends, and reef locations. PLAN submarine captains are undoubtedly adept at negotiating these features; they are forced to regularly. The Yuan’s small size allows it to maneuver more easily within shallow and confined littoral regions.

This is key, as shallow littoral’s bottom composition has a diminishing effect on sound propagation, sonar-target strength and noise levels — all of which acoustically shield submarines. The phenomenon a growing concern of the U.S. Navy.

“Picking up the quiet hum of a battery-powered, diesel-electric submarine in busy coastal waters is like trying to identify the sound of a single car engine in the din of a major city,” said U.S. Navy Rear Adm. Frank Drennan in a March story in the U.K. Daily Mail .

Given that SSK’s do not have the speed and longevity to evade quickly once detected, the Yuan’s terrain accessibility is a critical part of its survivability and operational ability. The advantages of shallow terrain are increased by the Yuan’s AIP system, which as mentioned before enables weeks of submerged time. This complicates U.S. anti-submarine warfare efforts, as snorkeling exposes SSKs to counter detection and is “the Achilles heel of the modern [conventional submarine].”

Nuclear attack submarines (SSN) like the U.S. Virginia-class (SSN-774) operate with comparatively greater difficulty in this type of terrain. While SSNs have enormous advantages over SSKs, shallow terrain partially limits the SSNs’s primary advantage: diving deep at high speeds after firing and thereby evade detection. Furthermore, maritime geography may circumstantially limit larger submarines physical maneuverability. It is conceivable that an adept PLAN submarine captain (A Chinese Günter Prien) could take advantage the Yuan’s shallow draft and wedge the SSK into a difficult-to-access channel or maritime feature, and thereby forcing higher-technology SSNs to fight on unfavorable terrain whose geography and acoustic signatures favor the defender.

The idea that PLAN naval architects designed the Yuan primarily for chokepoint control and anti-surface ASCM warfare is buttressed by the PLAN’s decision to maintain the Song-class’s double-pressure hull (two hulls: an inner and outer hull, rather than just a single-hull).

For technologically inferior navies like the PLAN, the main benefit to double-hull designs is the additional surface areas where sonar-absorbing, sound-dampening anechoic tiling can be placed. While double-hull designs were used in the past to increase survivability (Russia’s Kilo-class’ double-hull achieved 32 percent reserve buoyancy, which enabled it to remain buoyant even when one of the submarine’s six compartments and adjoining ballast tanks were flooded), it is extremely unlikely that a double-hull would keep the Yuan operational after being hit with a modern torpedo like the U.S. Mark 48.

Double hulls come at a significant capability trade-off: they are costly, difficult to repair, and increase platform size, which in turn increases hydrodynamic drag, lowers engine efficiency, cruising range, and therefore longevity. Efforts to limit size expansion would necessitate internal volume reductions, which would reduce platform capability in areas such as magazine depth, fuel supplies, habitability, for example. In contrast, single-hull designs are lighter, faster, have a higher internal volume-to-displacement ratio, and yet are less stealthy, given likely PLAN technology (The United States has used single-hulls for decades because of advanced U.S. quieting technology).

The PLAN was clearly willing to accept capability limitations and reduced range and speed in order to improve the Yuan’s stealth. The use of a double-hull reinforces the Yuan’s status as a chokepoint guard, rather than a platform that would use AIP to “act like an SSN for a day” and seek-out targets in blue water.

The PLAN may have accepted this trade-off because the Yuan does not need catch up with fast-moving surface ships in order to threaten them: the C-802 anti-ship cruise missile has a range of 180 kilometers. The Yuan is also able to use the PLA’s new supersonic ASCM (YJ-18). The YJ-18 “has been described as having a cruise range of 180km at Mach 0.8 and a sprint range of 40km a Mach 2.5 to 3.0.” An estimate from the Pentagon’s most recent Chinese military capability report places the maximum range of the YJ-18 at 250 nautical miles. This is significant, as supersonic sprinting speeds reduce the reaction time available to and complicate the work of a ship’s countermeasures.

ASCM’s free Yuan captains from spending crucial electrical reserves in attempts to maneuver into torpedo range (Yu-6 torpedo range est. 45 km), after which the Yuan could potentially be left with little power left. Furthermore, the crew proficiency needed to excel in ASCM-based anti-surface warfare is less than that needed when prioritizing torpedo-use. The latter requires complex maneuvering based on imperfect information, all the while leaving the very littoral areas that partially shield them from higher-technology SSNs.

Advantages of a Small Platform: Cost

While higher-technology nuclear attack submarines like the U.S. Virginia-class have great advantages over SSKs and could root out hidden Yuan’s over time, delousing SSK’s is complicated by their relatively “cheap” cost. Navies like the PLAN that (thus far) prioritize SSKs can field larger numbers of platforms than would be the case with a purely nuclear-submarine (SSN) force like the U.S. Navy.

The AIP-equipped French Scorpène and Russian Lada-class submarines, both dimensionally similar to the Yuan, have an export price of $450 million. The larger Japanese Soryu costs around $540 million (That is the sixth Soryu’s cost, which benefited from pre-existing designs and a well-established shipyard: a situation the Yuan shares). The cost of the Yuan is unknown. Various reports have priced Pakistan’s recently purchased Yuan-class SSKs between $250 and $325 million, or above $500 million. However, these early-reports are likely inaccurate. Moreover, Pakistan’s purchased Yuans may in fact be its smaller (cheaper), non AIP-equipped export version called the S-20. Lastly, such reports do not shed light on the cost-per-unit for the PLAN. A wide range of economic and political factors influences weapon export prices, to say the least about the variability of domestic production costs.

Generally speaking, the Yuan’s production cost is likely comparable to it’s dimensionally similar Lada-class and Scorpène-class counterparts. That puts the Yuan’s probable cost around 1/6 of a Virginia-class SSN ($2.8 billion). While SSK capabilities are in no way comparable to SSNs, such comparatively low-costs directly contribute to the PLAN’s two-to-one undersea platform quantitative advantage vis-à-vis its U.S. counterparts and the rapid pace of Yuan-acquisition, as shown previously. In the event of a conflict, PLA undersea numerical superiority may slow U.S. efforts to clear areas like the South China Sea of Yuan-class SSK’s. This would buy precious time for the PLA to accomplish its goals during a Taiwan contingency or territorial dispute in the South China Sea.

Delousing an area of SSKs is complicated by the fact that AIP increases the Yuan’s range, giving the Yuan more areas to hide or position themselves. Sweden’s Stirling-engine equipped (150kW system) Gotland-class can maintain 5 knots for 14 days submerged, which translates into a 1,680 submerged nautical mile range. While the Stirling AIP-equipped Yuan is larger than the Gotland, Taiwan is only 95 NM from China, the Senkaku islands only 200 NM, and even the Spratly Islands only 634 nautical miles.

Important to this discussion is the close proximity of Taiwan. With Chinese shores relatively close-by, Yuan captains may feel freer to expend energy reserves chasing their targets. Even when low on power AIP would likely enable a Yuan to creep back to the relative safety of China’s close littoral regions. It is conceivable that a fully fueled and charged Yuan could conduct operations around these areas while only rarely having to surface and recharge.

Furthermore, AIP expands the areas that would have to be searched, thereby slowing and complicating surface naval activity in the targeted area. This scenario will only grow worse, as improvements in battery technology enhance the range and longevity of conventional submarines.

Conclusion

The Yuan was designed be a small, cost-minimizing, quiet ASCM platform intended to excel at anti-surface warfare. The PLA may be seeking to deter or defeat U.S. intervention and rectify its weakness in ASW by producing a large number of expendable anti-surface warfare-specialized SSKs. The PLAN’s large SSK fleet would complicate U.S. ASW even if the pace of SSK elimination were high. Such a scenario would buy precious time for the PLA in a Taiwan contingency. The PLA may be seeking the ability to force a situation where the U.S. Navy’s surface fleet would be required to either accept a high level of risk, or operate further away from Taiwan.

However, such generalized conclusions do not take into account the effectiveness of U.S. missile defense, ASW, C4ISR, space and cyber abilities. In other words, trade-off analysis suggests what the PLA may hope it’s submarine force can achieve tactically, operationally, and strategically; not what it is guaranteed to be capable of. Nevertheless, the Yuan and its AIP system are the harbinger of greater challenges to U.S. power projection in the Western Pacific.