WASHINGTON, D.C. — The U.S. Coast Guard has determined — through independent analysis — it needs three heavy and three medium icebreakers to cover the U.S. anticipated needs in the Arctic and Antarctic, commandant Adm. Paul Zukunft, told reporters on Tuesday.

However, how the service gets to that number or how it will pay for the ships is still an open question.

In the next year, the service will know if its laid-up heavy icebreaker USCGC Polar Sea (WAGB-11) will be worth restoring. In parallel, the service is exploring whether or not to begin the design work for a new class of ships or if leasing foreign ships will be the way for the U.S. to manage its Arctic and Antarctic requirements, Zukunft said.

“It’s either recapitalization with new ships, restore an old ship that may buy you ten years of service,” he said.

“We’ll be able to make an assessment reactivation by next year and at that point we need to move forward but we probably need to move forward in parallel tracks as well so we’re prepared to look at funding set aside, whether it’s for reactivation of an old ship or start preliminary design and construction of a new icebreaker.”

As for leasing icebreakers, legally the Coast Guard can crew the ships and operate a leased ship but the funding for a long-term deal would have to come at the front of an arrangement.

“The challenge with the lease option is you score that lease all up front, you can’t spread the cost out over 30 years and then you lose the flexibility of where and how you operate that ship,” Zukunft said.

The need for the ships is mounting as reduction in the icepack in the Arctic makes the region more attractive to not only natural resources exploration but also tourism and compared to the other Arctic nations.

The current U.S. icebreaker capability is modest.

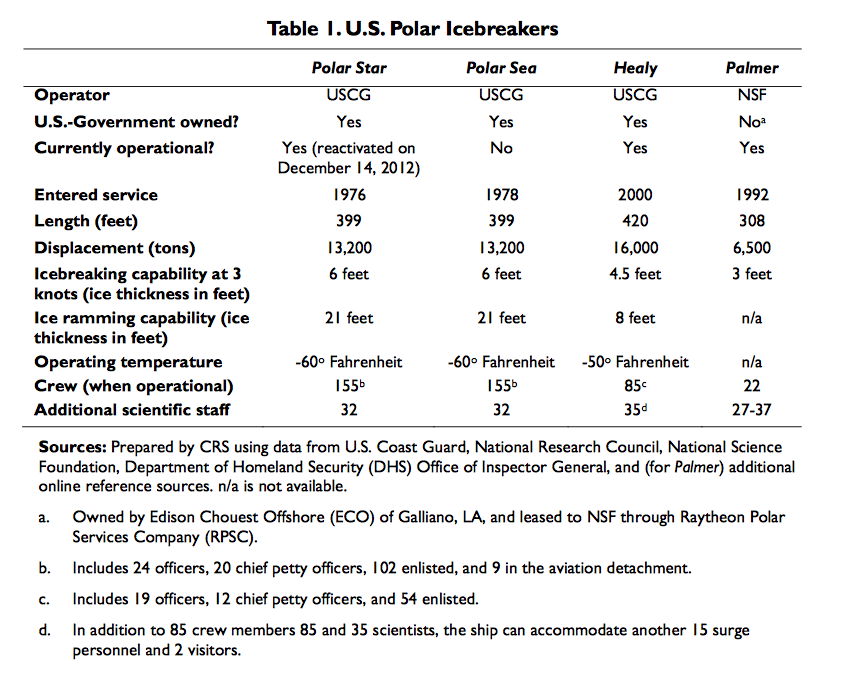

Currently the Coast Guard has two operational icebreakers — heavy icebreaker USCGC Polar Star (WAGB-10) and medium icebreaker USCGC Healy (WAGB-20). The National Science Foundation also leases a research icebreaker — Nathaniel B. Palmer.

In comparison, Russia fields almost 40 with up to a dozen more planned or under construction, according the Coast Guard’s 2013 review of the world’s major icebreakers.

Additionally, U.S. icebreakers have additional missions beyond creating channels for other ships.

“When you look at what do you need an icebreaker to do in the 21st century, first it needs to break ice — obviously — so it needs to have access. It needs to be able to communicate if there’s a contingency in the Arctic, you don’t have shore station you can base out of, it has to be at see, so it has to be a command and control platform (C2),” Zukunft said.

“It has to be able to do law enforcement and do scientific research, also do search and rescue and not only that, if you’re operating in the Arctic — under the polar code — we anticipate there will be very stringent environmental requirements which ships that were designed in the 1970s do not meet today in 2015… All of those need to be taken into account if we’re going to operate in 2015.”

The C2 and communications requirements are extremely important. The Arctic is among the most difficult places in the world to operate. Not only because of the cold and lack of human habitation, but because communication and guidance satellites are not optimized for higher latitudes making both tasks exceedingly difficult.

Six different U.S. agencies have missions in the Polar regions and the Coast Guard may insist that those agencies help pay for the ships.

As part of its Fiscal Year 2015 budget, the Coast Guard asked for $6 million towards design work for a new icebreaker class, according to a January Congressional Research Service report. To date, the service has received about $9.6 million in design funds starting in Fiscal Year 2013.