On Jan. 3, 2015 Boko Haram militants initiated an attack on Baga, a village situated near Lake Chad in northeastern Borno state, Nigeria, and on the villages surrounding it.

Over the next several days, insurgents, according to some accounts, succeeded in killing more than 2,000 people; 30,000 others fled for their lives.

The attack on Baga—Boko Haram’s deadliest to date—could be the single most lethal terrorist event since the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

Yet, it is only one among hundreds of attacks, bombings, kidnappings, and assassinations carried out by Boko Haram since 2009.

Those include: the Aug. 26, 2011 bombing of the U.N. house in Abuja; the Sept. 29, 2013 massacre of students at the Gubja College of Agriculture; and the April 15, 2014 kidnapping of 276 schoolgirls from Chibok. In the latter, only the particularly heinous and lurid nature of the event succeeded in arousing short-lived worldwide attention.

Perhaps because of the passionate use by Abubakar Shekau—Boko Haram’s leader—of anti-colonial, anti-Western, anti-secular, and jihadist rhetoric, observers have paid a great deal of attention to the insurgency’s sectarian dimensions—Boko Haram’s attacks on Christians and so-called apostate Muslims. A comprehensive examination of Boko Haram’s attacks, however, reveals that inordinately, ethnic minority groups, regardless of their religious affiliation, are Boko Haram’s most common target Haram.

Nigeria’s Ethnic Politics

In Nigeria, it is often said all politics are ethnic politics. So, for researchers to overlook the ethnic aspects of the insurgency—the ethnic identities of Boko Haram’s victims and the reasons they have been targeted—is an extraordinary lapse.

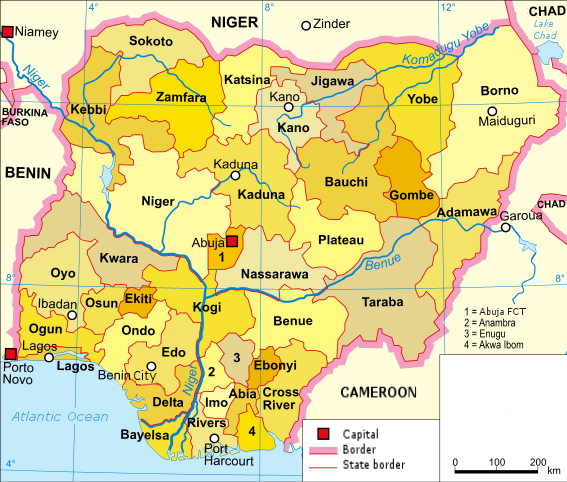

Northeastern Nigeria, where Boko Haram emerged, is a region dominated by the Kanuri, who make up three-quarters of Borno State’s 3.2 million people and who overshadow their neighbors politically. Boko Haram members are, it has been reported, largely Kanuri. There are, however, in addition to the Kanuri people, many smaller ethnic groups that live in the region, mostly in southern and eastern Borno State and in neighboring Yobe and Adamawa states. Overwhelmingly, the majority of attacks carried out by Boko Haram in Borno and on its borders have been carried out in areas inhabited by small ethnic minority groups such as the Buduma, Shuwa Arab, Mandara, Marghi, Chibok, Laamang, Glavda, Bura, and a host of other small groups, with relatively few attacks carried out in areas populated by the Kanuri.

An analysis of more than 200 Boko Haram attacks in Borno from May 14, 2013—the date on which Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan imposed a “state of emergency” on Adamawa, Borno and Yobe states—to 31 August 2014 suggests that ethnicity—non-Kanuri ethnicity—rather than religion, is the dominant characteristic identifying Boko Haram’s victims.

• Boko Haram launched dozens of attacks on the cities of Ngala-Gambaru and Dikwa and surrounding villages located in the overwhelmingly Muslim Shuwa Arab territory of eastern Borno killing hundreds, including local village heads, and destroying bridges leading to Cameroon.

• Boko Haram attacked the cities of Konduga and Bama and the surrounding villages in the overwhelmingly Muslim Manadara region southeast of Maiduguri nearly three dozen times, including: an 11 August 2013 attack on a Konduga mosque that resulted in the deaths of 44 worshippers; the 31 October 2013 attack on Gulumba village during which insurgents burned 300 dwellings; the 26 January 2014 attack on Kawuri village in which Boko Haram killed 85 residents (including a Muslim cleric), burned 300 homes, and set 4,000 residents in flight; the Feb. 11, 2014 attack on Konduga, during which Boko Haram burned 2,000 homes, schools, and other structures (all told, 80 percent of the village); and the 19 February 2014 attack on Bama and the Emir of Bama’s palace.

• Following roughly two dozen attacks over the course of a year, on July 18, 2014, Boko Haram attacked Damboa in the mostly Christian Marghi belt in south Borno. More than 100 residents were killed in the initial attack and about 3,000 displaced before Boko Haram raised its flag over the city. The siege of Damboa lasted more than two weeks, during which time insurgents cut electrical lines, blacking out Maiduguri. On 6 August 2014, Nigerian security forces who recaptured Damboa found 95 percent of the city destroyed and corpses littering the streets.

• Following the April 14, 2014 kidnapping by Boko Haram of 276 schoolgirls from the Girls Government Secondary School in Chibok, Boko Haram continued to periodically attack villages across the predominantly Christian Chibok areas of south Borno, burning churches and killing hundreds.

• After a wave of preliminary attacks on surrounding villages, on 10 April 2014, Boko Haram attempted to seize Gwoza, in the religiously diverse Lamaang region of southeastern Borno. Attacks continued with villages and churches burned across the region, and the kidnapping the Emir of Gwoza, Idrisa Timta, on 29 May 2014. On Aug. 6, 2014, Boko Haram entered Gwoza killing about 100 inhabitants before raising its flag over the city. Within weeks, Boko Haram began to use Gwoza as a springboard from which it could launch attacks across the region.

• Biu and the villages surrounding it in the religiously diverse Bura ethic region of southern Borno suffered more than a dozen attacks culminating in the July 24, 2014 Boko Haram raid on Garubula village in Biu local government area, during which the district head and 11 others were shot dead by Boko Haram fighters.

• Baga, in the overwhelmingly Muslim Buduma ethnic region of Borno’s northeast, and the scene of recent devastation, also suffered numerous Boko Haram raids prior to January’s deadly siege, including a April 19, 2013 raid that resulted in the destruction of 2,000 of Baga’s buildings and the killing of 187 residents.

Systematic Attacks

Villages and towns across the ethnic minority regions of Nigeria’s northeast have been attacked by Boko Haram repeatedly—and, it appears, systematically—resulting in more than 10,000 deaths and the displacement of a staggering 1 million people, according to some accounts. Combined, those attacks and the refugee crisis they have engendered bear all the hallmarks of ethnic cleansing.

Andrew Bell-Fialkoff, the author of Ethnic Cleansing, says that though it can take many forms, “ethnic cleansing can be understood as the expulsion of an “undesirable” population from a given territory due to religious or ethnic discrimination, political, strategic or ideological considerations, or a combination of these.”

While there presently is no legal definition of ethnic cleansing, against the backdrop of the growing humanitarian crisis presented by the Yugoslav Wars (1991–1999), in 1992, the U.N. Security Council’s Commission of Experts concluded that “‘ethnic cleansing’ means rendering an area ethnically homogenous by using force or intimidation to remove persons of given groups from the area.” In the face of events now unfolding in Nigeria’s northeast, it seems difficult to conclude that what is occurring at the hands of Boko Haram is anything but ethnic cleansing.

Mustering the Will To Kill

The decision to engage in ethnic cleansing, says Abram de Swaan, the author of The Killing Compartments: The Mentality of Mass Murder, is the consequence of numerous, complex and interwoven social and psychological considerations over a prolonged period of time. Almost without exception, a period of indoctrination, during which time the would-be aggressors cast themselves as the victims of injustice and, in turn, portray the target population as the real antagonists, precedes actual violence. “Without exception,” says de Swaan, genocidaires emerge “within a supportive social context” which assures them impunity for their crimes. In Nigeria, a nation where ethno-religious tensions routinely boil over in fits of deadly violence, where perpetrators are protected through patronage, and where often mere lip service is paid to the rule of law, such impunity would seem even more assured.

The presence in Nigeria’s northeast of “numerous, complex and interwoven social and psychological considerations” suggests possible factors that could have contributed to Boko Haram’s decision to engage in ethnic cleansing. Among them are: climate change, desertification, and growing environmental scarcity in the Lake Chad region; mounting ethno-religious tensions and their attendant political and economic implications; and a religious ideology that views Christians and other “unbelievers” as neo-colonialists intent on the destruction of Islam and responsible for the deprivations of northern Muslims.

Environmental Scarcity

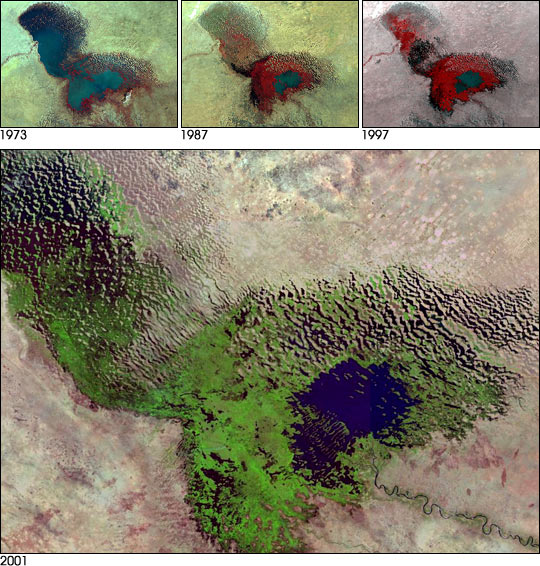

Nigeria’s northeast is drying out with serious consequences for the region’s inhabitants. Since the 1960s, Lake Chad, which formerly covered 15,000 square miles of northeastern Nigeria, northern Cameroon, western Chad, and southeastern Niger, has shrunk to just 500 square miles, and very little of that in Nigeria. Ragged Baga town, once a thriving fishing village, is now, with the lake having receded, stranded amid clay firki plains and savannah; the lakeshore is more than 20 kilometers (12 miles) away. And, with the retreat of the lake, so, too, have gone many livelihoods. Meanwhile, the desert is inexorably advancing. The streets of Maiduguri are often covered with wind-blown sand from the Sahel. At the same time, competition for diminishing resources is abetted by dramatic population growth. Where once 10 million people depended on the life-giving waters of Lake Chad, now twice that number depend on a shrinking lake no longer able to support all who need it. Inevitably, competition for water and arable land has increased, and may explain why Damboa, the agricultural heart of Borno state, and the communities surrounding the cropped river valleys spreading out from the Gwoza hills, have become scenes of violence.

Borno’s Breakup

Ethno-religious tensions in Borno state having important political and economic implications for the Kanuri and the wider North have grown. By the middle of 2009, agitation by Borno State’s southern minority ethnic peoples, among them the Babur Bura, Chibok, Guduf Waha, Guduf Nagadeo, Kanakuru, Mandara Marghi, Ngoshe Glafda, Ngoshe Gaha, Pulka, and Tera, for the creation of their own state—Savannah—out of the southern third of Borno reached a peak. More than 200 representatives from Askira/Uba, Bayo, Biu, Chibok, Damboa, Gwoza, Hawul, Kwaya-Kusar, and Shani local government areas lobbied for the creation of the new state as a means of escaping the oppression of the Kanuris who have dominated Borno politics since that state’s creation in 1976. There have been, since Nigeria’s founding, several rounds of state creation, each meant to enhance national stability and to provide ethnic minority groups some measure of equality in access to political and economic power within Nigeria’s federal system, however; rather than enhancing the peaceful coexistence of Nigeria’s multitude of ethnic groups, state creation has almost always been accompanied by violence from those on both sides of the issue, including attacks on government institutions, traditional and religious leaders, and ethno-religious opponents. Should Savannah state be allowed to come into existence, its creation would have negative impacts on the Kanuri and the wider north. Not only would Borno State lose its most agriculturally productive region, it would see—as would every other existing state—its share of Nigeria’s oil wealth, allotted through the Distributable Pool Account (DPA), reduced. More galling to northern political elites, the creation of Savannah state would mean the thrusting of a majority-Christian state into the heart of the Muslim north, an act they would view as a southern Christian attack meant to weaken the political and economic power of the north.

Ideological Authority

Further, evidence suggests that the political mainstream of northern Nigeria, or at the very least a significant portion of it, are in accord with a religious-political ideology which holds that “Western imperialism . . . has gradually and subtly eroded and supplanted the values and ideals of [their] pre-colonial societies . . . [and] initiated [them] into a virulent materialism which has since subverted [their] social morality, weakened [their] social fabric and crippled [their] socio-economic and political progress,” one northern politician said. The agents of this form of imperialism are described by Saudi Islamic scholar Bakr ibn Abd’Allah Abu Zayd as “the enemies of God, the worshipers of the cross and other unbelievers” who have, through the spreading of Western secular ideas, “thrust hidden swords into the hearts of Muslims to colonize their doctrine and ideology and way of life, until the Muslim world’s morals and trappings become like those of the Western world, and the truth of the house of Islam is overthrown.” The “only hope of escaping from this culture of corruption, decay, and mismanagement,” said one prominent Northern politician, is “to dislodge the hegemony and monopoly of western liberalism. . . .” That ideology, often suggested by observers as having originated with Boko Haram, substantially predates the insurgency and is, in fact, part of a decades-old debate within the Nigeria and the wider Islamic world about how to balance the requirements of modernity with the principals and beliefs of Islam. Important to this discussion is that such an ideology, when employed to recruit and radicalize an aggrieved population, especially in the presence of other compounding circumstances such as the environmental and ethno-religious factors described, could set the stage for the demarcation of a target population and, possibly, ethnic cleansing.

What Boko Haram Is Now

Whatever the Boko Haram insurgency was at its onset, and whatever its reasons for doing so, it has become, in part at least, a mechanism for the ethnic cleansing of non-Kanuri minority groups from Nigeria’s northeast. If the attack on Baga portends anything, it is that Boko Haram’s ability to inflict mass violence and bloodshed on the people of Nigeria’s northeast has increased beyond Nigeria’s capacity, or willingness, to confront it. Even as Nigeria stumbles towards its upcoming presidential elections—a faceoff between Muhammadu “War Against Indiscipline” Buhari, the northern Fulani Muslim who previously ruled Nigeria as military head of state from 1983 to 1985 after seizing power in a coup d’etat, or the incumbent president Goodluck Jonathan, the southern Ijaw Christian under whose watch the insurgency has grown out of control—reports suggest that Boko Haram stands capable of launching further assaults on Borno State’s capital, Maiduguri, a city whose swelling refugee population has few places left to run.