WASHINGTON, D.C.—The head of the U.S. Navy’s shipbuilding and maintenance arm spends a lot of time thinking about risk.

The risks of building some ships to a commercial standard, the risk of cyber attacks to ship systems, and the risks of determining how much maintenance can slide on a surface ship while at the same time getting the ship to its expected service life all focuses of U.S. Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA) head, Vice Adm. William Hilarides in the last year.

“The Navy is in as much demand as in anytime, probably since 1945,” Hilarides told USNI News in an extensive late November interview.

“Whether you’re burning chemical weapons or defending the Persian Gulf or keeping things calm in the South China Sea, that demand is up and the budget is clearly down.”

Sitting in the former U.S. Coast Guard commandant’s office in the command’s Buzzard Point offices—dubbed NAVSEA West—Hilarides talked to USNI News about NAVSEA’s newly revised strategic business plan, the threat of cyber attacks on U.S. Navy ships and submarines and NAVSEA’s exploration of new ways to design and build its ships of the future.

‘Business As Usual Won’t Work’

With more than 60,000 employees and a budget of $30 billion Naval Sea Systems Command is one of the Navy’s largest divisions.

In 2013 Hilarides inherited the command that was just turning a corner in the maintenance of the U.S. Navy surface fleet. His predecessor—now-retired Vice Adm. Kevin McCoy—had helped rebuild NAVSEA’s ability to work on its surface ships after ten years of neglect and the scathing 2010 Fleet Review Panel, commonly known as the Balisle Report after the head of the effort, retired Vice Adm. Philip Balisle.

Despite the reforms in NAVSEA, Hilarides has had to handle ongoing funding challenges born of the 2013 government shutdown and the ongoing sequestration cuts that were part of the 2011 Budget Control Act (BCA), and the risks NAVSEA has to take and still keep the fleet functional.

“How do you do that? You have to change the way you think about cost, how do you do things, think about doing them differently. Business as usual won’t work in that context,” he said.

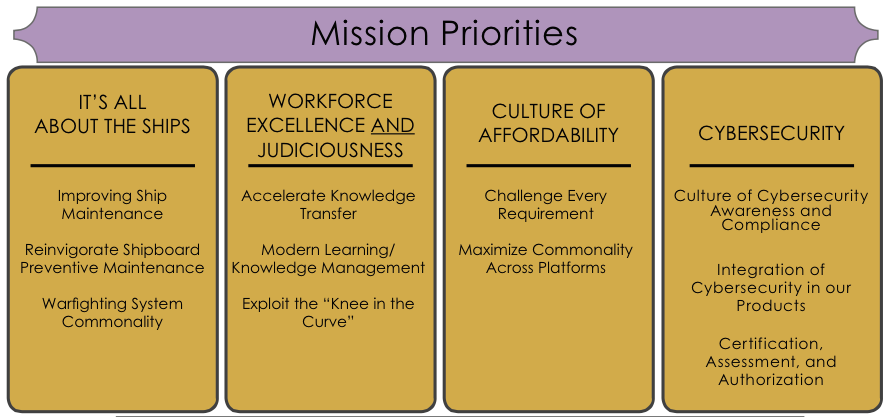

NAVSEA has attempted to shake up the way its long-serving technical side thinks about the risk in maintenance and shipbuilding through its newly revised strategic business plan issued in November, which includes affordability as one of its prime tenets.

“It’s easy to go conservative if you have all of the money. Restore [the component] to the way it was built, well that costs X. But can we can restore it to a condition that will make it satisfactory for five years until the next time we go into dry dock?” he said.

“We’re not good at that risk taking and risk balancing.”

Shipbuilding

Cost drivers don’t just stop at ongoing maintenance.

NAVSEA is also evaluating the military risk-affordability relationship in the new classes of ships just entering the fleet or currently on the drawing board.

Hilarides used the Mobile Landing Platform (MLP) as an example of the emerging cost-conscious line of thinking in NAVSEA, which includes building ships (or ship components) to a commercial standard instead of military specifications (MILSPEC).

Engineers asked, “’Why isn’t it MILSPEC? Why didn’t we build it to the full shock and survivability [standards]?’” he said.

“Then you have to say operationally, this isn’t going to the front line. . . . In the past my engineers would have said, ‘They’re going to send it right to the front lines. We have to make sure it’s [MILSPEC].’ No, they’ve told us this is how they’re going to operate it. Here’s your direction on that, use the commercial standards.”

Hilarides said its corps of engineers, which has been with NAVSEA for decades, has been challenged by the cultural shift brought on by reduced budgets coupled with a high demand of the service.

That cultural shift on cost is front-and-center in the ongoing requirements discussion for NAVSEA’s upcoming major surface ship project, the next generation amphibious warship LX(R).

“We are debating the snot out of that ship,” he said.

“Cost matters a lot and so we spent more time on the cost—once we set the base requirements on the cost—than on any ship I can ever remember; because it’s going to be a big ship, controlling its cost will be absolutely essential if the amphibious force stays the size it needs to be.”

LX(R) went through several rounds of requirements debate between the Marines, the Navy’s surface and amphibious requirements shops in OPNAV, and the cost-conscious office of Sean Stackley, assistant secretary of the Navy for Research, Development & Acquisition (RDA).

Stackley’s tenure has been marked by an effort to hold down costs of Navy shipbuilding and keeping a weather eye on requirements.

“I think Secretary Stackley has been very forward-leaning on this conversation, actually driven it in many ways. We haven’t brought cost into the requirements discussion yet. Go back and do that again with the costers in the room. And go back and do that again with the designers in the room,” Hilarides said.

“I think he gets a lot of credit for driving a great conversation about requirements and what they cost before you spend a nickel.”

The current conversation on LX(R)—and other emerging ship designs—is possible now because of the way the Navy is interpreting acquisition rules based on the 1986 Goldwater–Nichols Act.

Following the sweeping reform of the legislation, the Navy generated some of the most stringent acquisition guidelines in the Pentagon, which would have made the current debate impossible.

“I would say there are artificial barriers out of the acquisition reforms that came out of Goldwater-Nichols that we put on ourselves. We said we’re going to have this nice high barrier, OPNAV is going to have to write requirements, hand them over to you, you’re going to go work on them and then hand it back when you’ve completed something. I think we artificially raised those barriers,” Hilarides said.

“That wall today is pretty low. When that team got together on LX(R) that was everybody. It was requirements authority, it was the costers, it was the ship-design people, people who figured out what kind of radar, all together saying: Are there other ways to meet the requirement? What would you think of that? And very much of that went on in a very open way. . . . That complex interaction was very difficult in the time when you [just] threw a complex set of requirements over the wall.”

Early Navy estimates suggest the lead ship of the LX(R) program could cost up to $1.64 billion with follow-ons costing about $1.4 billion for a total of 11 ships, according to information from the service. Since then the Navy has been reluctant to talk numbers on the program.

Cyber

Not only does NAVSEA have to work on its enduring mission, it has the added challenge of keeping its ships and systems safe from emerging cyber-security threats.

New to the latest revision of the NAVSEA strategic plan is a tenet focused on cyber security.

With ongoing budget constraints, NAVSEA is looking to design cyber protections into its emerging systems for its new construction and ships that come in for updates.

“This isn’t a hard-right rudder. We’re not going out and spending hundreds of millions of dollars tomorrow to start changing our system, but if we design it in now, and when it is, we’ll have all the levers and the controls necessary to defend ourselves as the threat evolves,” Hilarides said.

The move from NAVSEA is in line with other efforts from Navy’s 10th Fleet—the service’s operational cyber arm—and the so-called cyber-awakening task force led by the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations (OPNAV) Information Dominance corps.

“It’s a new area of warfare, rapidly evolving and once you start it’s hard to see where it is, why would somebody stop,” he said.

“My characterization would be that up until a couple of years ago it had been something that someone else some one took care of for you and the cyber awakening is about all of us waking up [and saying] it’s not just about the back office guy that sets up the network.”

Cyber warfare and security historically have been difficult for the public to understand and sometimes even harder to articulate, as Hilarides found in October.

Speaking before the Naval Submarine League Symposium in McClean, Va., Hilarides used a story of vulnerabilities DARPA researchers found in the computer networks of modern cars hackers that could use to give incorrect readings on a speedometer, engage or disable breaks, or affect steering.

In connecting the analogy to the Navy, Hilarides pointed to a vulnerability in the control system of the Virginia-class submarine’s (SSN-774) Caterpillar backup diesel generator, which could compromise other mechanical systems on board.

He was wrong.

“I should not have used that company’s name and pointed that there was a specific weakness in our system. As it turns out, Caterpillar has some of the most secure control systems on the planet,” he said.

“Caterpillar was pretty mad at me, actually. I didn’t realize how good Caterpillar was until the president of Caterpillar came in and talked to me.”

As it turns out, Caterpillar will be used as a model of how NAVSEA will design cyber protections into its control systems moving forward, he said.

“Our systems are engineered well and there’s no specific weakness,” he said.

“[The car example] is really indicative of a potential future weakness.”

Maintenance Delays

NAVSEA has struggled with ongoing maintenance delays resulting from the government shutdown of 2013 that resulted in several reported delays in work on some of the Navy’s most high profile ships—aircraft carriers and submarines.

Hilarides said a major issue is manpower.

“In [2013] the sequester and the shutdown resulted in me not being able to hire in my public shipyards for almost nine months. I lose about 1,000 people a year across the four yards due to attrition, and so during those nine months, we went down a thousand but we were in an increasing requirement,” he said.

It took NAVSEA nine months after the freeze was lifted to hire back to pre-shutdown levels and it continues to hire at a maximum rate but there is still a so-called divot in the maintenance schedule.

“First thing that happens is that [attack submarines] go long. The next thing is the [ballistic-missile submarines] go long and then eventually it impacts the carriers, as you saw on the Eisenhower,” he said. “Is it directly attributable only to the sequester? No. Was it a culminating event in a real problem in our public shipyards? Absolutely and we’re bailing as fast as we can.”

Hilarides anticipates the public shipyards to reach the necessary manning levels in about the next year, “which will be when we stop falling behind and we start getting ahead and starting to recover” and see timelines for maintenance get corrected by 2018.

“I hope to do it sooner. I certainly get plenty of input from the Fleet commanders to do it faster than that, but until we’re manned to the job I’m going to keep having trouble with the schedules to meet,” Hilarides said.

“It’s a tough business.”