Many are asking why the Turks are not doing more to enable the Kurds and their feared Peshmerga forces to more effectively attack the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS or ISIL) military forces. Surely the Turks see this through the ancient ‘the enemy of my enemy is my friend” lens?

In fact, the Turks and the Kurds have a complex relationship. If you asked a pragmatic Turkish national leader who they fear more as an existential threat to the future of Turkey, the money is the majority would say the threat is the Kurds and the Pesh — not ISIS.

It is also important to remember that while would-be peacemakers dined at Versailles, the Ottoman Empire did not just slide gently into the Bosporus – it simultaneously imploded and exploded with a violence of energy and realignment that still echoes today from Armenia to Ankara and every point in modern Turkey, the inheritors of the Ottoman Empire.

Kurds – who after the fall of the Ottoman Empire found themselves dispersed across Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey – have a rich history as fierce warriors and able administrators.

Salah ed-Din, known to us as Saladin, liberated Jerusalem (1187) from the Crusaders, conquered Syria and Egypt, and left a huge red palace compound overlooking Cairo to prove he had been there.

Today, the Kurds (who some alleged assisted the Turks in the Armenian Genocide) have since 1923 fought a simmering struggle against all four nations, but more so against Turkey, where the majority of them live, according to Charles Glass’ book, Tribes with Flags: A Dangerous Passage through the chaos of the Middle East.

Kurds want autonomy and the ability to govern themselves. Syria and Iran would probably wish them well and feel a sense of good riddance. In Iraq, it comes down to control of the northern oil fields, so Iraqis will not be quite so sanguine.

Turkey has long harbored hard earned hatred of the violent acts of the Kurdish struggle[ii], and so will be guarded and concerned on any process that might lead to a Kurdish nation-state that may well take Kurds (and Troubles) away from Turkey, but might take land and other resources in the hard-scrabble southeast as well, according

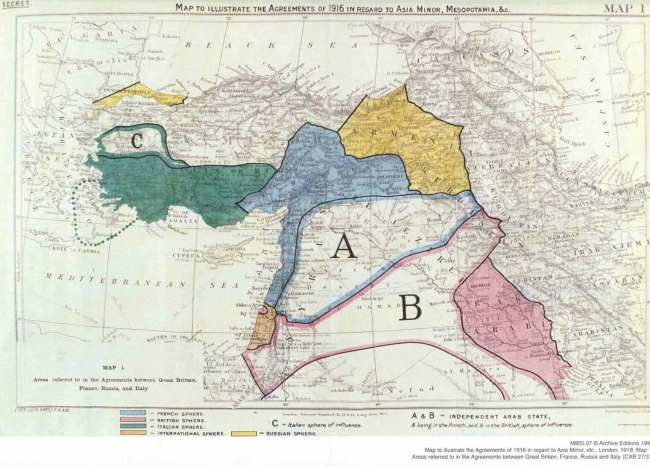

Finally, the shadow of Sykes-Picot still looms: Russia was originally assigned administration of ‘Kurdistan’ but after the Revolution, the new government denounced all Tsar signed agreements, and the British quickly rushed in to seize that former Russian-ruled region.

Thus the Turks – NATO Members, holders of the keys of the Dardanelles and Bosporus Straits via the Montreux Convention, with a new government structure, a rapidly growing economy and still locked outside the European Union membership gates – have their own reasons for how they view the people and area of the Kurdish zone.

The Turks will be very careful in engaging the Kurdish Peshmerga to fight against ISIS or other forces – a resurgent, well-armed Kurdish force with acclaim and recognition in the media and Western capitols, may be perceived as only a few steps away from full blown calls for nation-statehood, wrote Heather Wagner in The Kurds.

What, then, can ‘the West’ and the U.S. do to influence a change in Turkish policy? Conversely, what Turkish actions are ‘good enough’ to maintain our own strategic interests with Turkey? Put differently, the loss of a strong partnership with Turkey, engaged in NATO, involved in Europe, and constraining Russia is a far graver threat to U.S. security interests than IS. A supportive Turkey, acting in their own national interests while assisting the U.S. obtain long-term policy goals in the Middle East should be the ultimate objective of U.S. foreign policy right now. Like any other enduring relationship, ours with Turkey is complex, and must be adroitly managed to ensure long-term strategic benefit for the U.S. across the region.

In many ways, the Turks and Kurds are an epic story for the ages. I spent a few months on the Iraqi side of the border as a company commander in OP PROVIDE COMFORT in 1991, and I got to see first-hand, albeit as a company grade officer, the dynamic (and sometimes downright dicey) interactions of Kurds, Syrians, Turks, Iraqis and Iranians. I was also in Istanbul in June 2013 when the riots began, so I have some perspective on the current state of converging – and conflicting – interests of Kurds and Turks in this complex situation.

What is making this significantly challenging to policy makers are four events in Turkey in the last 18 months:

1) Riots in and protest movement in Istanbul

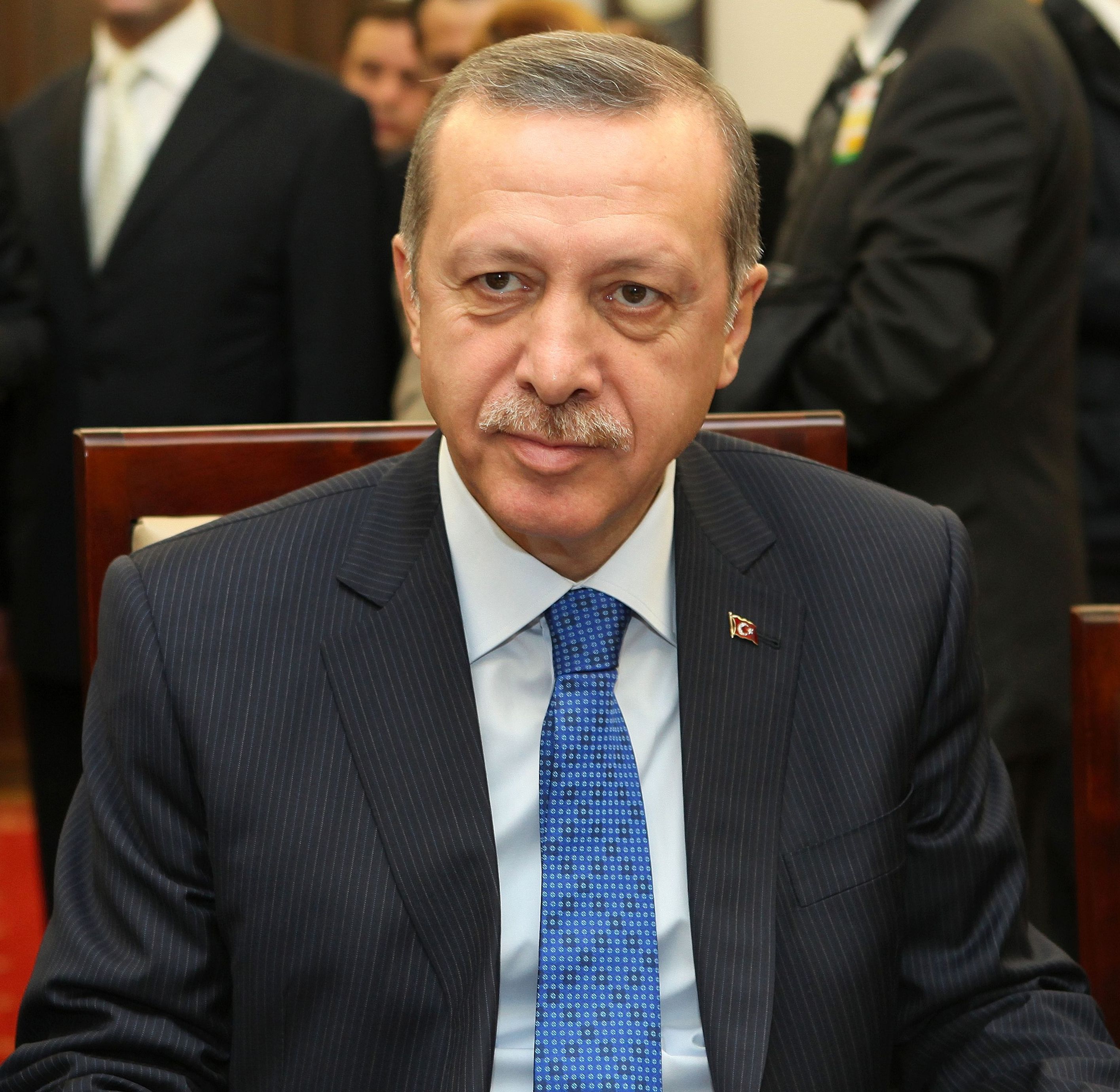

2) Recep Tayyip Erdoğan usurpation of power as President from the Prime Minister

3) The EU’s ‘reinforced’ position of ‘Turks Need Not Apply’ for membership and lastly

4) The re-emergence of the Black Sea as a pivot point for power and politics and Turkey owns the Montreux Convention and naval forces access to the Black Sea.

1. Turkey is both a modern secular state and an Islamic ‘hub’ for the Greater Levant and Middle East. What roles ‘regular’ Turk history plays, what place the Ottomans are afforded in the modern historical lexicon, and how to relate to both Islam/Allah and Europe are very hard for Turkey to figure out. As a result, the decision to take a planned museum and convert it to a secular shopping mall was not solely about urban development – it was about what defines the Turkish soul. How modern Turkey broke away from it’s past, disestablishing the Ottoman Empire in 1922 and founding a new Turkey, is a key part of this. Unfortunately, the two great unresolved issues from this turbulent time are Armenia and Kurds. For all of the cruelty heaped upon both Kurds and Armenians, the Kurds are still stateless. A Turkey unsure of its relationship with the West is more likely to go its own way, whether in building a mall or a museum, or in defining its 21st century relations – and borders – with the Kurds.

2. Erdoğan was not exactly subtle when, as Prime Minister, he moved to amend the Constitution to give the President more power, effective about the same time that he would be able to run for office. It is up there at the level of U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt threat to stack judges on the Supreme Court – except that Erdoğan got away with it. The real concern now is what will he do with that power and position, and how will power transition and be employed (legally as opposed to extra-legally) by Erdoğan’s successors as PM and President. That will take at least another decade to sort out. Washington has a hard time seeing past a news cycle or an election cycle. Being able to think at least a decade ahead and where we want the U.S. to be in our relationship with Turkey and the Black Sea region, as well as with Iran, Iraq and Syria, is the overarching concern for Washington right now. Thus, national leaders will cautiously try to discern strategic opportunities and then craft a strategy and build the sustaining policies. Erdoğan’s Turkey is going to be a challenge – but it will also offer some opportunities in the region. They may not look like what we would call a great deal – but there will be options to explore and where possible leverage.

3. The EU is not growing at nearly the rate that Turkey is, demographically or economically. The Turks are an economic and diplomatic force with which to be reckoned. A recent United Kingdom assessment of Turkey notes that: “By 2045, it is likely that the EU will include most of the countries in the western Balkans. Turkey is likely to become increasingly important to European security, as the size, capability and increasing modernization of its armed forces means that it may have one of the more capable militaries in Europe, as well as the Middle East.” While Turkey will not be at the gates of Vienna or Budapeszt en force again, they are important as a cultural as well as geographical bridge to the Middle East as well as Central Asia. At some point the EU is going to have to find a “Pragmatic Sanction” to continue to smartly work with Turkey; a Turkey closely-held and incorporated may be uncomfortable, but a Turkey isolated and marginalized will be downright dangerous. As we engage in the “Great Game II” with Russia and energy from throughout Central Asia, isolating Turkey does not work well to our advantage; put differently, we may have even larger fish to fry.

4. For the U.S. and our Blue Water naval tendencies, we tend to overlook the ‘lesser’ Seas and Oceans – but they are significant in theatre / regional politics and strategies. The Black Sea has once again become very important because of the Russians wanting to get stuff to Syria – and the ability to easily interdict it – as well as US/NATO wanting to get to the Black Sea to confront the Russians. While the Turks are the authorizing authority for passage, of note it is the Russians who complain about it the most vociferously. Until the Russians get Novorossiysk up and running (est = 2020) they will have to reinforce Sevastopol. The bigger issue, between Ossetia and Crimea, all the way around, is the strategic re-armament of the Black Sea and what that might mean a decade from now.

Just how much support can we expect the Turks to willingly give the Pesh – against whom they have fought a simmering and nasty war for more than two decades – in the fight against ISIS? It all comes down to interests and politics. One thing is certain – it will not be solved over breakfast in the White House or on the Sunday morning talk shows filled with overblown punditry. It will require the President to deal directly with Erdoğan’s – he needs to get on a blue and white and fly to Turkey and cut deals.

The Turks have interests, the U.S. has interests, and you look for where they might start to align. The Turks will try to leverage this to their advantage – so will we – that is why it is called state-craft not state-science. To confront and contain the so-called Islamic State, we need a Roman-style proxy to go and ruthlessly kill a lot of people, preferably in public, in large numbers in a small amount of time, to put this non-sense back to bed – until the next time the hydra rears one of its many heads and we go do it again.