The heart of the United Kingdom’s nuclear submarine enterprise could be cut out if Scotland leaves the U.K. in Thursday’s referendum on Scottish independence, British leaders have warned repeatedly over the last several months.

Scots voting “Yes” for independence say they’re happy to see the subs go.

At issue are the Royal Navy’s four Vanguard-class ballistic missile nuclear submarines (SSBN) and their payloads stationed at Her Majesty’s Naval Base Clyde, tucked into a narrow bay in Scotland’s Southwest.

For more than 40 years, the Royal Navy has used Scotland to homeport its nuclear deterrent fleet and nuclear attack submarines (SSNs).

However — if the Sept. 18 secession referendum passes — an independent Scotland will almost certainly evict the Royal Navy’s boomers and their submarine launched ballistic missiles (SLBM) from an independent Scotland.

“We believe that nuclear weapons have no place in Scotland,” read a 2013 policy paper published by the Scottish Government.

“We will therefore advocate that a written constitution should include a constitutional ban on nuclear weapons being based in Scotland.”

Separatists would consent to let the base remain until 2020, leaving precious little time for the U.K. Ministry of Defense (MoD) to find new homes for the aging Vanguards and the warheads for their Trident-II D5 SLBMs.

Military officials have warned the separation of Scotland from the rest of the U.K. would especially hurt the Royal Navy.

“The U.K. is deeply respected for its maritime contribution to NATO, with its maritime deterrent through its ships and submarines and marines, and that whole piece is part of NATO’s contribution to security,” wrote Adm. Sir George Zambellas — First Sea Lord of the Royal Navy — in April according to an U.K. Press Association report.

“Taking that apart would give us a much weaker result. The two components would not add up to the sum of the whole.”

Scots for independence argue that the U.K.’s reliance on its nuclear deterrent for protection has left Scotland unprepared for conventional conflict.

“The U.K.’s wasting money on Trident has left Scotland with totally unsuitable conventional defense capabilities – particularly maritime protection,” wrote Keith Brown, Scottish Government minister for veterans and former Royal Marine in a Sunday opinion piece.

“With independence we can invest in defense and security forces which reflect our needs in the 21st Century.”

HMNB Clyde — and the about 160 nuclear warheads stored there — has been the target of several protests and is a major political sore spot with the Scots long predating the independence push.

View Moving the Vanguards in a larger map

The Faslane base was stood up in the mid-1960s as a homeport for the Royal Navy’s four Resolution-class submarines — 8,500-ton boomers fielding 16 Polaris A-3 missiles. The nearby Naval Armaments Depot at nearby Coulport stores the warheads.

Since the Polaris era, Royal Navy has made significant investments in HMNB Clyde to accommodate the Vanguards and the missiles and warheads.

Any accommodation for the Vanguards in Britain’s existing naval bases will be expensive and the logistics of basing the boomers in France or the U.S. are complex — not to mention the politically challenging.

“Several options exist as a replacement base but none appear to be as good as the current facilities in Scotland,” Eric Wertheim, author of the Naval Institutes Combat Fleets of the World, told USNI News on Friday.

“Some are considered too close to population centers while others raise sovereignty issues or require very extensive financial investment and modification.”

U.K. Basing

If the U.K.’s sole nuclear deterrent leaves Scotland, the Royal Navy will have to replace not one but two facilities — the operational base for the Vanguards at Faslane and the warhead storage and loading facility at Naval Armaments Depot at Coulport.

There are some U.K. options, but none are ideal from the Royal Navy’s perspective.

View Southern Options in a larger map

When the Royal Navy was searching for a base for the quartet of Resolutions in the 1960s, it created a shortlist of ten locations, according to the 2002 paper published in The Nonproliferation Review, titled: The United Kingdom, Nuclear Weapons and the Scottish Question.

Of those original locations, two — one in Wales and one in Southern England — might be suitable for Vanguard basing, according to authors Malcolm Chalmers and William Walker. Chalmers was one of the original architects of basing the U.K. boomers at Clyde.

The most obvious choice is in England — HMNB Devonport.

The largest naval base in Western Europe, the site already conducts the nuclear refueling and refits for the Vanguard boats.

But space at the installation is already at a premium and it might be impossible to maintain prescribed minimum safety distances between a replacement for the Naval Armaments Depot at Coulport, other ships at the installation and nearby housing developments.

“The main issues with Devonport did not relate to recreating the facilities of Faslane, but of Coulport, and without Coulport, there is no deterrent,” read a 2012 report from the U.K. Parliament’s Scottish Affairs Committee.

Milford Haven in Wales is a deep-water port and could easily accommodate the comings and goings of the boomers. It’s also far from population centers. However, there’s a large oil refinery near by and military leaders in the 1960s scrapped the plan due to safety concerns.

A possibility not on the original Resolution list is Barrow-in-Furness, home of the U.K.’s BAE Systems submarine manufacturing base in Northwest England. The Royal Navy would have difficulty creating an operational base due to the lack of a reliable deep-water approach to the facility.

“That would restrict submarine access to convenient monthly tides without significant dredging, and the size of the dock which would not, at present, have room for more than two Vanguard-class submarines,” read the report from the Scottish Affairs Committee.

“Coulport is not just a storage site, but also possesses the huge floating dock where the warheads are placed inside the missiles.”

Any of the U.K. sites would require an expensive and intensive construction program that could take up to a decade to complete. At least one U.K. think thank said the cost for a new facility could be almost $5 billion.

Some Scottish leaders have said they want the warheads and the Vanguards gone by 2020.

U.S. and France

View Foreign Options in a larger map

Two sites that could more easily accommodate the Vanguards and the nuclear warheads are on foreign soil — France and the U.S.

The likeliest foreign home for the Vanguards and the payload would be Naval Submarine Base Kings Bay, Ga.

Begun as a military ocean terminal in the 1950s, the base began converting to a homeport for the U.S. boomer fleet starting in 1976.

The base is already integral to the U.K.’s ballistic missile submarine organization.

A total of about 58 Trident missiles were bought by the U.K. and are considered “mingled assets” with U.S. Tridents, according to Combat Fleets.

“The missiles are randomly selected from the U.S.-U.K. stockpile at Kings Bay, Ga. and loaded onto submarines. The British submarines then sail for the Naval Armaments Depot at Coulport,” reads the entry in Combat Fleets.

With the U.S. converting four Ohio-class submarines to guided missile carriers in the last two decades, there would likely be room to accommodate the warheads and the Vanguards.

“We must decide how important, in the short term, the word independence is in terms of our nuclear deterrent. After all, we rely on the U.S. for our missiles and for an awful lot of intelligence,” said Air Commodore Andrew Lambert with the U.K. National Defence Association — a group that advises U.K. should increase defense spending — in a Saturday speech quoted in the U.K.’s Sunday Express.

“We could easily run Trident from the US for ten years, and prepare the rest of the U.K. for whatever the follow on might be.”

The U.S. Navy would not comment on any proposal to relocate Vanguards and warheads to Kings Bay when contacted by USNI News.

The French Navy has kept the submarines of its Force océanique stratégique (FOST) at Île Longue nuclear submarine base since the 1970s.

Currently, its four Triomphant-class SSBNs operate from the Brittany peninsula.

Île Longue might have become more politically palatable for the British in recent years. France and the U.K. have two bilateral defense agreements ongoing — including operating both British and French aircraft from the nuclear aircraft carrier Charles de Gaulle (R91).

Though closer than Kings Bay, space maybe tight in the facility and it might not be able to accommodate all four Vanguards.

Next Steps

If Scotland votes for independence on Thursday, it is unclear what the U.K.’s next steps will be with regard to its nuclear deterrent.

The U.K.’s sole nuclear deterrent are the ongoing Vanguard patrols following a late 1990s retirement of their nuclear bomber force.

In an era of shirking U.K. defense budgets, preserving the boomers and the U.K. nuclear deterrent could be financially unreasonable given the extra cost of developing permanent basing those submarines elsewhere in the U.K.

The split could also make the U.K.’s SSBN Successor SSBN program more difficult to fund.

English politicians, as well as Scots, have been critical of the cost of the so-called 100 billion pound Successor program.

“Nuclear deterrence is aimed at states, because it doesn’t work against terrorists,” said Tory Member of Parliament James Arbuthnot in 2013.

“You can only aim a nuclear weapon at rational states not already deterred by the U.S. nuclear deterrent, so there is only a small set of targets.”

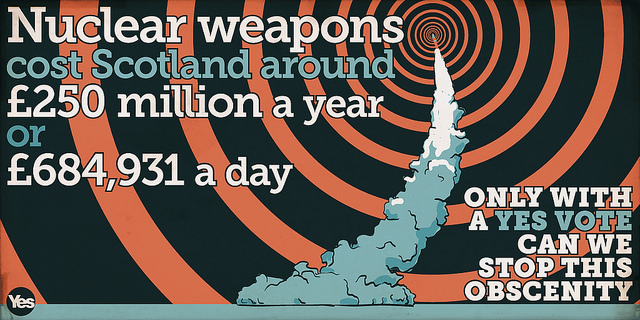

Much of the Yes vote literature breaks out the cost of the Trident program and compares it to domestic spending for social services — and the message is appearing to resonate.

According to the most recent public opinion polls — the split between a Yes and No vote is still too close to call — a dramatic shift toward Scottish independence in only the last few weeks.

Recently, U.K. leadership has undertaken a mad scramble to shore up support to keep the British Isles together.

“If the British nuclear deterrent is forced out of Scotland, one of the alternative options will have to be chosen,” Wertheim said.

“But that will likely have a significant and negative impact reverberating from the Royal Navy to the national economy, and eventually could be felt by all 28 members of the NATO alliance.”