The U.S. Navy’s recognition of a 72-year-old war grave began when an Australian scuba diver plucked a bent trumpet from 120 feet below the Sea of Java.

The mangled horn belonged to one of 1,100 sailors or Marines assigned USS Houston (CA-30) — a cruiser sunk by Imperial Japanese Navy ships in one of America’s earliest skirmishes in World War II.

The 2013 recovery of the trumpet — albeit by a well-intentioned diver — caused an association of Houston survivors to warn the Navy that the wreck is at risk to less scrupulous operations.

“[There] has been a long standing concern over allegations [divers] were salvaging and pillaging that wreck,” John Schwarz, executive director of USS Houston CA-30 Survivors Association & Next Generations, told USNI News on Thursday.

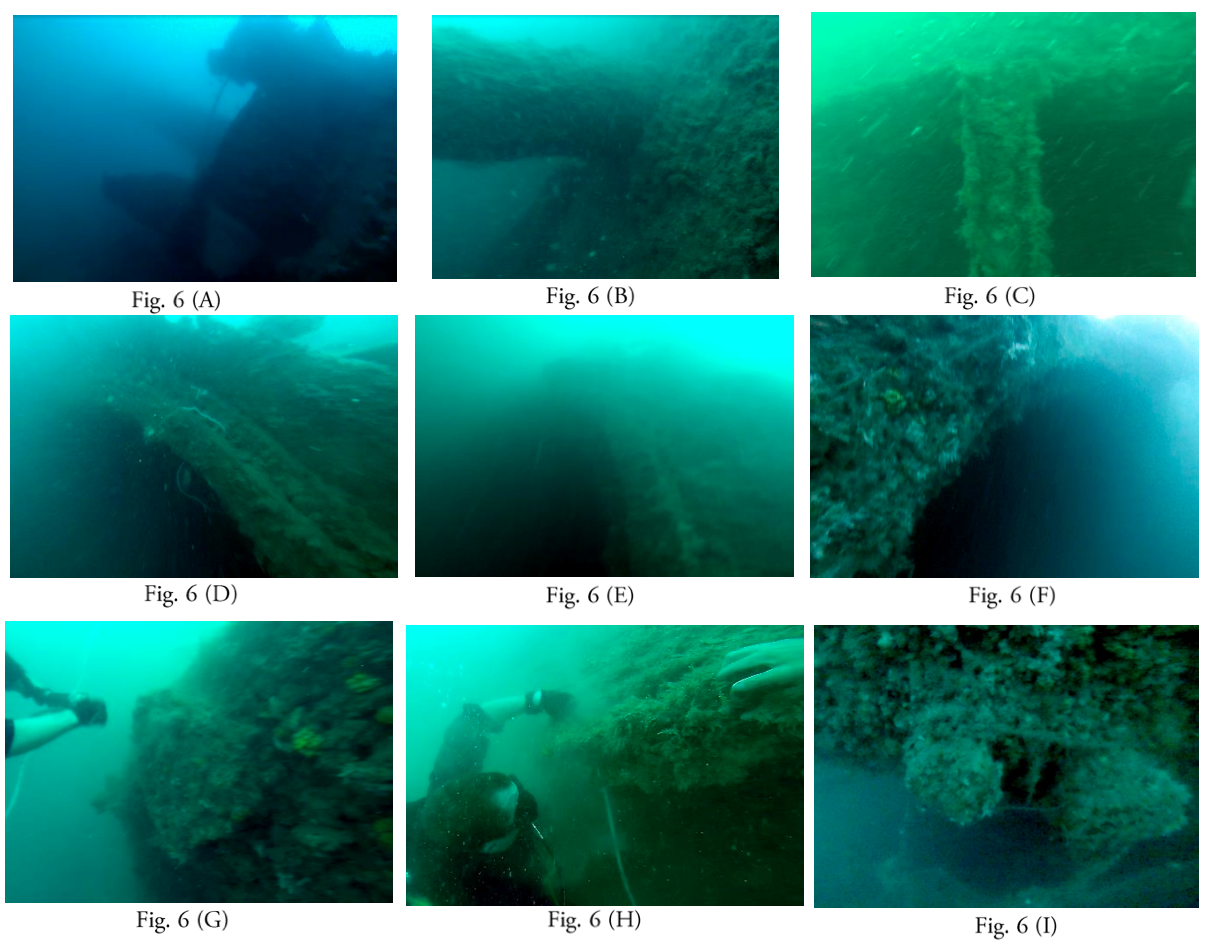

The service’s official examination of the wreck in June— in a diving exercise with sailors from Mobile Diving and Salvage Unit 1 (MDSU), the Indonesian Navy and U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC) —confirmed what Schwarz and his association had feared.

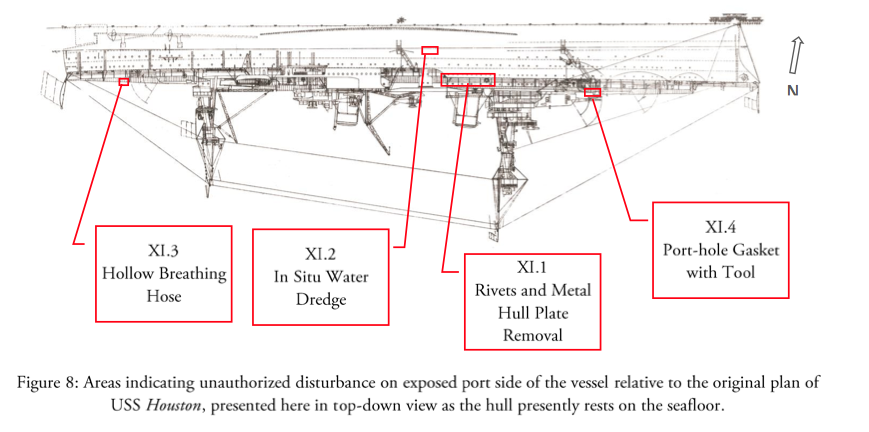

“The DIVEX revealed and documented conclusive evidence of systematic unauthorized disturbance of the site,” according to a July 25 NHHC Underwater Archaeology Branch obtained by USNI News. “Evidence suggests ongoing unauthorized recovery of unexploded ordinance from the vessel, raising public safety and security concerns.”

The Navy surmised that additional disturbance of the wreck would “potentially impact human remains within or adjacent to the hull.”

The site is the final resting place of hundreds of U.S. sailors and Marines.

‘The Galloping Ghost’

Unlike the site of USS Arizona (BB-39), sunk during the attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, Houston’s wreck is much more obscure.

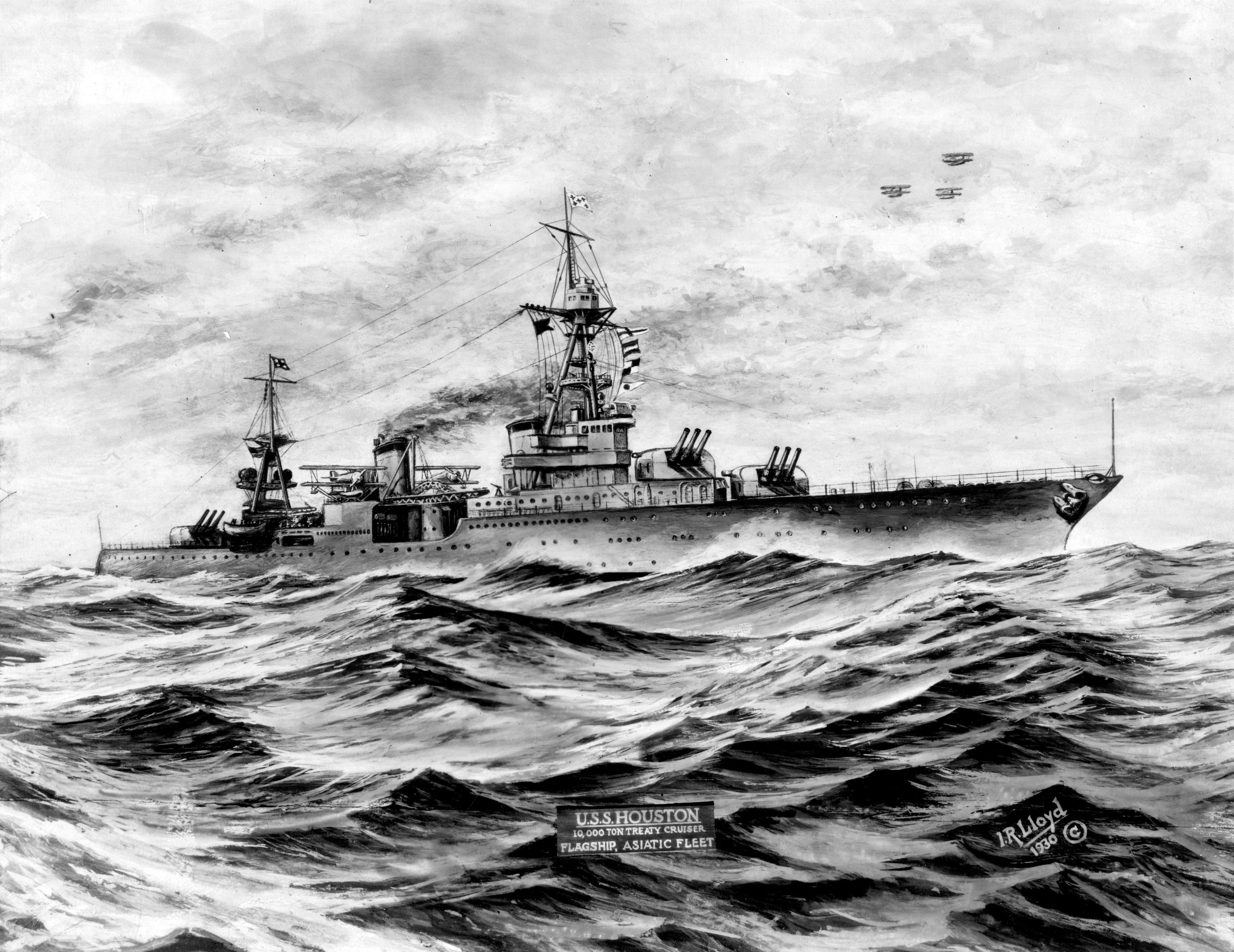

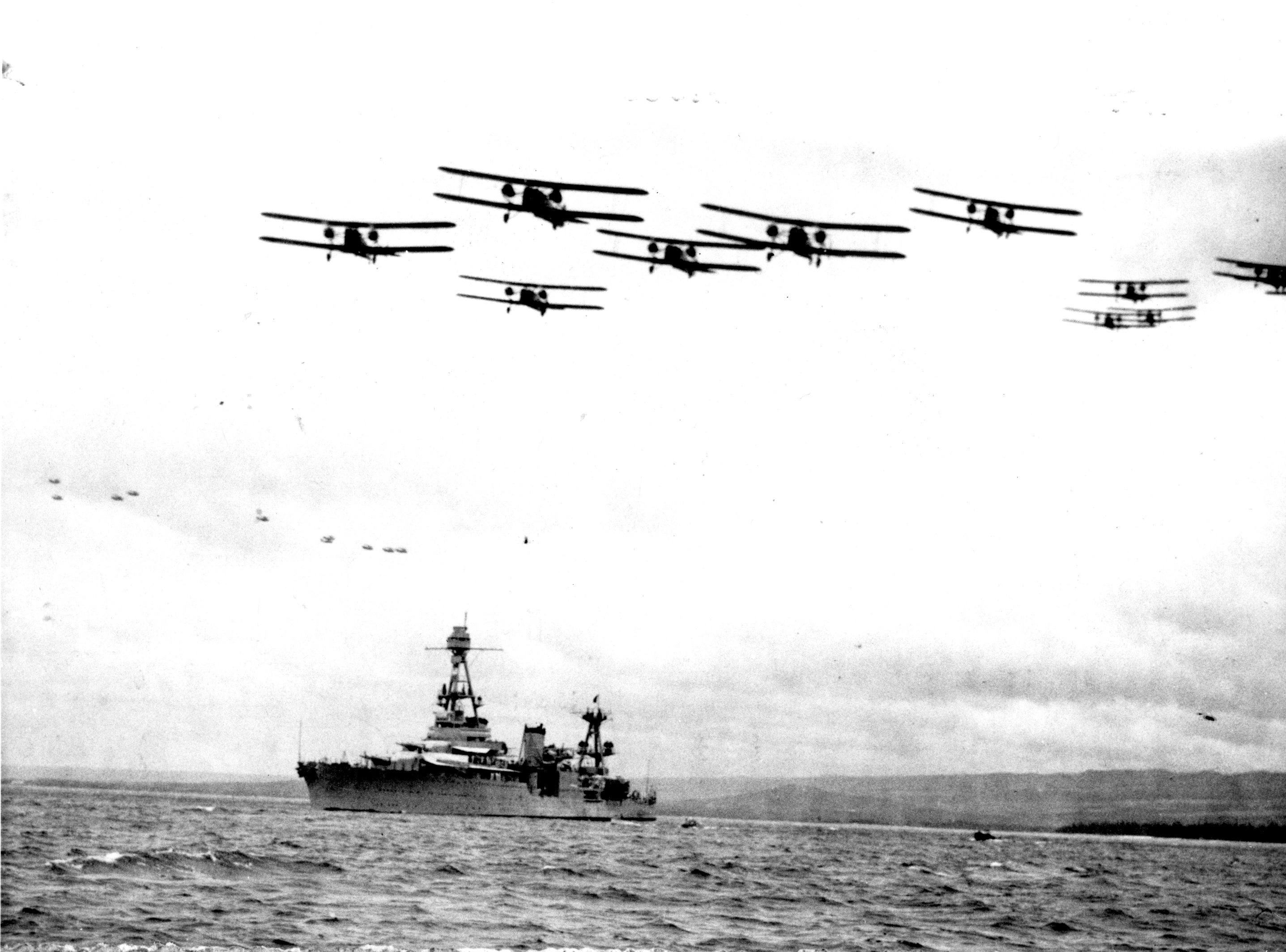

Before World War II, Houston was famous for transporting President Franklin D. Roosevelt on several long distance cruises and eventually became flagship of the now-defunct U.S. Asiatic Fleet.

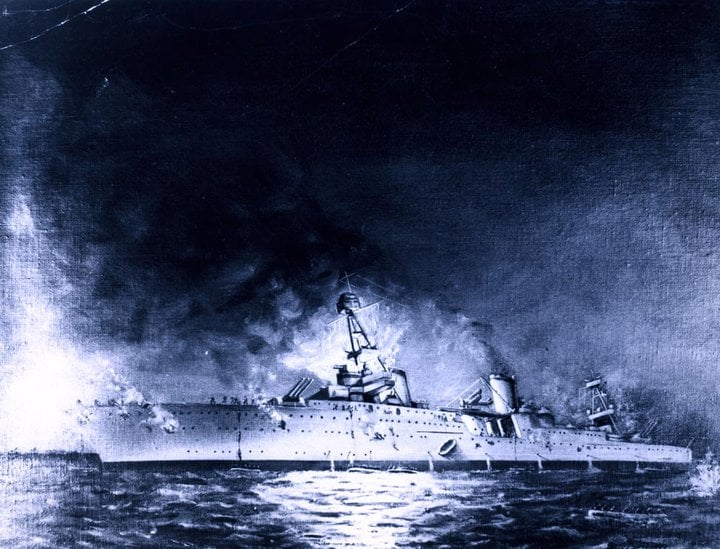

When war broke out between Japan and the U.S., Houston — nicknamed ‘Galloping Ghost’ — joined the early American-British-Dutch-Australian fleet, part of a short-lived Allied command based in Australia that suffered massive losses early in the war. Houston was lost early March 1, 1942, during the Battle of Sunda Strait — part of a failed attempt to stop the Japanese from landing on Java.

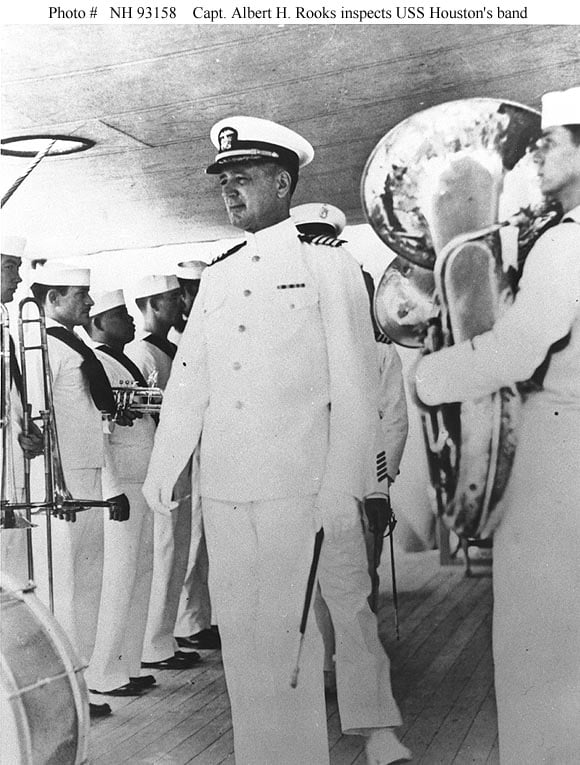

The ship’s skipper, Capt. Albert H. Rooks, died during the battle and received the Medal of Honor posthumously. Seven hundred sailors and Marines died either during the battle, went down with the ship or were lost after the ship went down.

The ship’s skipper, Capt. Albert H. Rooks, died during the battle and received the Medal of Honor posthumously. Seven hundred sailors and Marines died either during the battle, went down with the ship or were lost after the ship went down.

“A huge number of men survived the sinking, left the ship, clambered aboard rafts or held on to flotsam, but never made it ashore because of swift currents,” James Hornfischer, author of the book about Houston , Ship of Ghosts, told USNI News on Wednesday.

“Their fate is almost too horrible to contemplate, as many were likely washed into the Indian Ocean to die of exposure or shark attack.”

The remaining 368 crew were scooped up by the Japanese and put to work building the Burma-Thailand railway — made famous by the French novel, “Bridge Over the River Kwai.”

It wasn’t until the end of the war that the U.S. Navy realized there were survivors following the liberation of prisoners of war camps following the surrender of Japan. “It was such a grim story and it got buried all of these years,” Hornfischer said. “It’s a footnote to the misery for the first six months of the war.”

After the War

For decades, the ship lay at the bottom of the Java Sea — mostly undisturbed — until about the early 1970s.

“Diving and indications of diving on that ship go back at least into the 70s,” Schwarz said. “It was 1973 when the original bell of the ship, that had been brought up by pilferers and was located somewhere being sold in an auction.”

Schwarz’s father Otto — the association’s founder and barely 17-years-old when Houston went down — was able to recover the bell and have it installed at a memorial for the ship in Houston, Texas.

But other artifacts from the ship — like the trumpet — keep appearing on the surface.

Still, Houston has fared better than HMAS Perth (D29), which also went down in the Battle of Sunda Strait on March 1, 1942.

Salvage divers have already stripped much off of the Australian light cruiser, HMAS Perth (D29), which also went down in the Battle of Sunda Strait, according to a November report by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

“As best we can tell from the video footage supplied, most of the [Perth’s] superstructure – if not all of it – is gone, the guns from the forward turret, the A-turret are missing,” Andrew Fock, an expedition diver told ABC. “The gun houses for the two front turrets are missing, and most of the upper deck… is missing… The catapult has been removed, the bridge has been removed, the crane has been removed.”

Houston was not nearly as picked over but there was evidence divers have entered the hull.

The divers the Navy sent to examine the hull as part of June’s Cooperation Afloat Readiness and Training (CARAT) exercise with Indonesia.

The Indonesian and Navy divers found “systematic, methodical and ongoing unauthorized” efforts to salvage the wreck. The divers found loose plates were the rivets had been removed to provide easier access to the interior of the ship, dive hoses to support crews from the surface and tools to clear sediment from the wreck.

The divers set up buoys to mark the site and the Underwater Archaeology Branch issued an interim report on the findings.

Next Steps

How the U.S. can further protect the wreck is unclear.

“The law of admiralty [states] the Navy still retains ownership of these wrecks,” Hornfischer said. “[But] I’m not sure what they can do about it.”

Houston lies in Indonesian waters, U.S. ships can only enter with permission so the burden of protecting the site lies with Indonesian officials.

The Navy is still formulating next steps on how it will proceed with the wreck.

But a growing majority in the Houston association feel the wreck should be off limits to not only salvagers but also recreational divers, Schwarz said.

“We’ve come to learn over the years that literally tourists dive trips are sponsored and run using our ship as an attractive dive destination. It’s not sitting well with a growing majority of our group,” he said. “We consider it a scared burial ground and we would ask anybody and everybody to do what they can to protect its integrity.”

The Department of the Navy has more than 17,000 sunken ships and aircraft around the world — the majority from World War II.