The U.S. Navy and the U.S. Air Force are in the earliest stages of creating the requirements for their next generation of fighters but development of the engines that will power those aircraft are already well underway — and provide hints on what American sixth-generation aircraft will be able to do. One thing is already clear, both aircraft will be fast, long range and extremely efficient.

The engines for the F/A-XX and F-X programs will be the single most technologically challenging part of their development. As such, the Pentagon has already started work on developing those next generation propulsion systems.

Company officials with engine makers Pratt & Whitney and General Electric spoke with USNI News on the development work on their respective concepts to power those future combat aircraft.

“What we are seeing today, and this is especially true in all of the discussions around sixth-generation types of airplanes, the propulsion system capability is in fact driving a lot of the thinking about the size of the airframe, what the inlets and exhausts are going to look like, how much fuel capacity the aircraft has to have to meet the range requirements,” said Dan McCormick, General Electric’s general manager for adaptive-cycle engine programs.

“The propulsion system very much needs to be integrated into the design process of these next-generation airplanes.”

Both companies have started working on revolutionary new adaptive-cycle jet engines that will power the successors to the Boeing F/A-18E/F Super Hornet and Lockheed Martin F-22 Raptor.

These advanced engines would be able to vary their bypass ratios for optimum efficiency at any combination of speed and altitude within the aircraft’s operating range unlike today’s engines that are at their best at a single point in the flight envelope.

The powerplants have to be ready well ahead of air vehicle development—as both the Air Force and Navy discovered in the 1970s with the McDonnell Douglas F-15A Eagle and Grumman F-14A Tomcat with both type encountering severe difficulties with their engines.

Some of the key requirements for those next-generation fighters can be extrapolated from the goals set forth by the Air Force Research Laboratory and Office of Naval Research for their respective research and development efforts.

The Air Force has its Adaptive Versatile Engine Technology (ADVENT), Adaptive Engine Technology Development and NextGen programs mature next generation engine technology for a future F-X fighter while the Navy has its Variable Cycle Advanced Technology (VCAT) program looking at how those same technologies could be adapted for naval aviation.

Jeff Martin, General Electric’s expert on sixth-generation fighter propulsion, said that some of those extrapolated requirements suggest that a sixth-generation warplane will have much longer range than existing strike aircraft.

Further, the aircraft will be fast—with very high acceleration—and it will have excellent subsonic cruise efficiency.

“The bottom-line is it’s going to have to be a variable-cycle engine to meet those kinds of needs and not be a humongous airplane,” Martin said.

A variable-cycle engine would be able configure itself for maximum efficiency at any combination of speeds and altitudes. For example, it could act almost like a turbojet at supersonic speeds while performing like a high-bypass turbofan for efficient cruising at airliner speeds.

The indications thus far point towards aircraft designs that would have the finess ratio needed to supercruise—even if the requirements do not explicitly call for such a capability.

“The Navy has talked about a deck launched intercept mission where you get up and go, and get up some number hundred nautical miles away and you get there as fast as you can, as efficiently as you can,” Martin said.

That mission would be reminiscent of the F-14, which was designed to launch off the deck to intercept hordes of Soviet bombers before they could launch their payload of cruise missiles. While that mission disappeared after the collapse of the Soviet Union, a fast rising China may eventually pose a similar threat to the carrier strike group.

“It’s not clear to me that supercruise is going to be a major requirement, but it’s also not clear to me that it makes any difference at all. The airplane is going to have a pretty good fineness ratio, it’s going to be a supersonic airplane. And when its got that, and its got a variable-cycle engine in it, it’s going to be able to supercruise,” Martin said. “But whether they do it or not is a different story because to you do use more fuel when you supercruise.”

Tightly knit partnership

While the Navy and Air Force have separate programs, they are working closely together according to AFRL officials.

“The engine community is a tight knit group, we’ve had full transparency with the Navy,” the AFRL said in a statement released to USNI News.

“They’ve been invited and we welcome their participation in all the reviews. We gain additional insights from their subject matter expertise. They are a true partner in ADVENT and AETD.”

Martin offered some more details about the Navy effort.

“The VCAT program is really aimed a Navy specific items that they’re going to need for their next-gen fighter that would be additive to what AFRL is doing,” he said.

According to Martin, the VCAT effort—which will eventually lead to some propulsion rig testing—has proven to be extremely valuable. The Navy project has yielded important information on defining the exact cycles the engines should operate in—and that the airframe and engines need to be treated as an integrated whole.

For Pratt & Whitney, the VCAT effort also meant looking at if other parts of the engine—it might not just be the fan might be variable, said James Kenyon, general manager for next gen fighter engines for Pratt & Whitney. “It does bring a much greater degree of variability,” he said. “You may express than in a change in the bypass ratio a or change in some other things, but there is a great amount of flexibility that goes into that.”

Technological Maturity

For the Air Force, the goal is to ensure that the engine is at a relatively high level of technological maturity for a Milestone A decision in 2018 to proceed with the technology development phase of the F-X fighter.

However, a production engine would not have to be ready until a Milestone B decision to enter the engineering and manufacturing development stage. “Generally the thinking in here is that if you’re at TRL [technology readiness level] 6 by Milestone B, you’re in good shape,” Martin said.

With adaptive engine technology already set to hit the TRL-6 milestone before the end of the year, a production engine could be ready by 2021 if necessary.

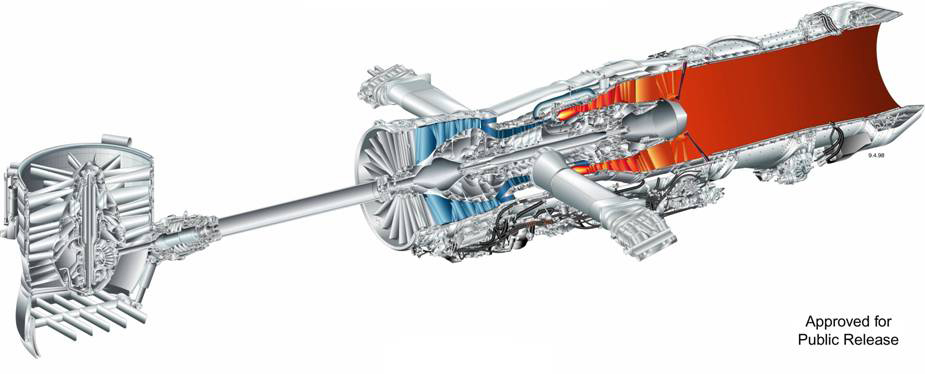

One of the key technologies behind the adaptive-cycle engine is the adaptive fan, which allows the engine to vary its bypass ratio depending on its altitude and speed due to a third stream of air. Air flows through the third stream as needed to increase or decrease the bypass ratio of the engine—or alternatively use the extra airflow for cooling.

“We can effectively vary the performance of the engine across the flight envelope,” Kenyon said.

At high-supersonic speed, the third stream can reduce spill drag by letting the excess air flow through the engine—however performance above about Mach 2.2 is still limited by the physics of air inlet geometry. “The third stream does help supersonically very much,” McCormick said.

For example, a fighter with an adaptive-cycle engine would use a low-bypass configuration where there is little bypass air flowing around the engine core during take-off and supersonic flight where high specific thrust is needed.

But the high jet-velocities of a low-bypass high specific thrust configuration mean low propulsive efficiency—which is bad for efficient cruise speeds. Thus, an adaptive fan would allow an engine to switch to a high bypass configuration for high propulsive efficiency once established on cruise conditions.

But it is not just the adaptive fan that will make future adaptive-cycle engines much more efficient than existing engines, new materials will allow the engine to run much hotter and at far greater pressure ratios than is currently possible.

The first variable-cycle fighter engine was the early-1990s-era General Electric YF120 engine that lost to what became the Pratt & Whitney F119 that powers the Lockheed Martin F-22 Raptor. “The YF120 engine was an adaptive-cycle engine focused in a totally different area,” McCormick said. “The ADVENT and AETD are primarily focused on fuel efficiency, certainly there is additional thrust capability for the AETD as well as significant improvements in thermal management. But the YF120 engine it was an adaptive cycle engine focused very much on the supercruise requirement of the aircraft.”

First Steps

The Air Force undertook its first steps towards developing sixth-generation variable-cycle engine with the Air Force Research Laboratory’s Adaptive Versatile Engine Technology (ADVENT) program in 2007. The AFRL’s goal was to bring the next-generation engine technology up to what the Pentagon calls TRL-6 and manufacturing readiness level six (MRL-6) — which means that prototypes can be readily built and tested “revelant” environment.

General Electric and Rolls-Royce were each awarded a six-year contract to produce demonstrator engines under the ADVENT effort. Pratt & Whitney’s ADVENT design was not selected for the program, but the company continued to pour its own resources into developing its technology in the hopes of securing follow-on work.

Pratt & Whitney’s efforts were centered on an early developmental version of a fan for the F135 engine that powers the Lockheed F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, Kenyon said.

The company used the fan to demonstrate an adaptive fan capability on a test rig at its compressor research facility.

“In that test we were able to demonstrate the ability to control the flow through the different streams,” Kenyon said. Eventually, Pratt & Whitney’s investment of its own funds would pay-off handsomely.

Adaptive-cycle realized

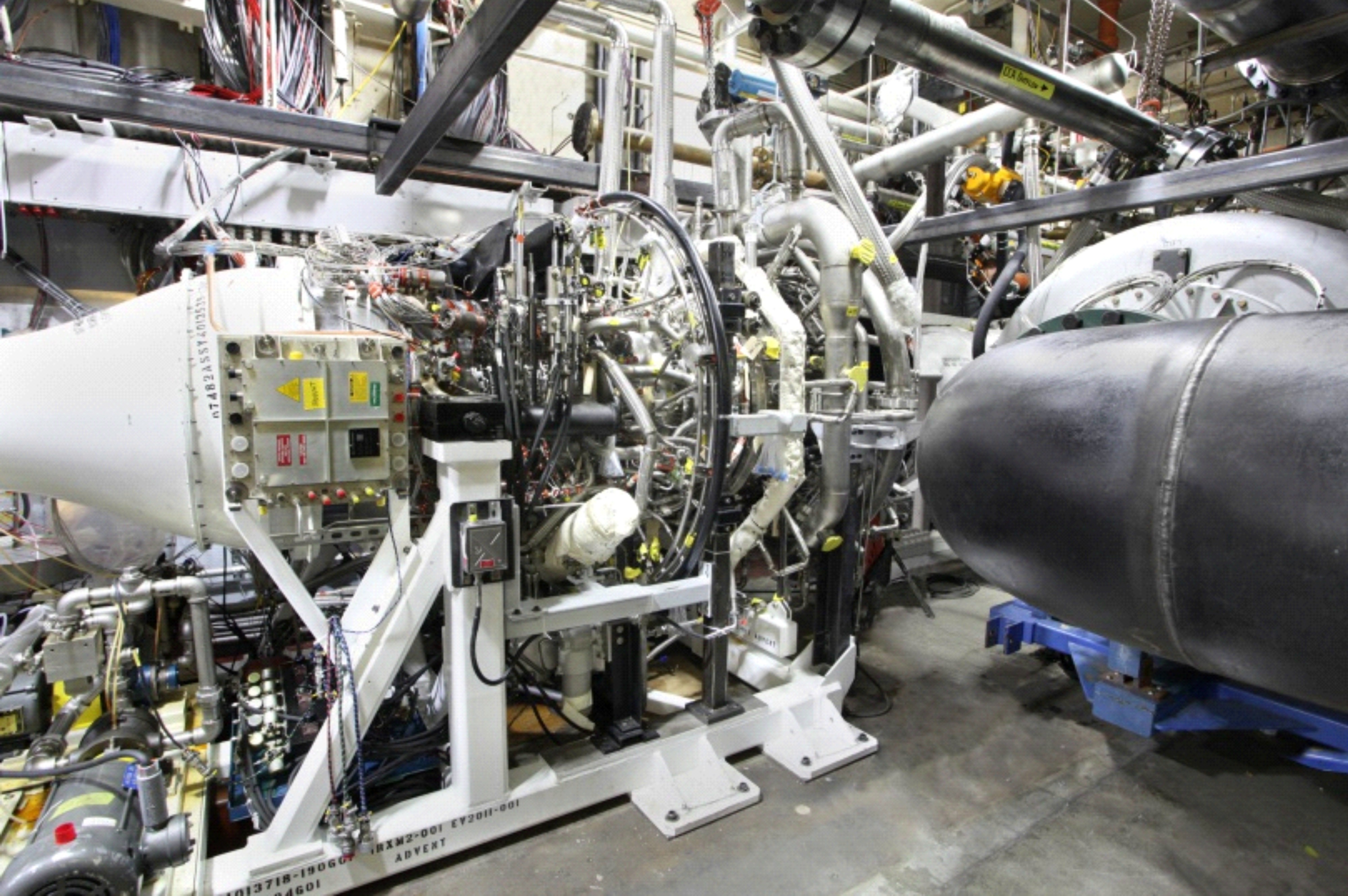

Meanwhile, after six years of development, General Electric began testing its ADVENT demonstrator engine on November 26, 2013. ADVENT engine testing is ongoing and is currently scheduled to end later this year—in the mid- to late-summer timeframe.

“We have a full-up adaptive-cycle technology engine here at Evendale [Ohio],” McCormick said. “It’s not an engine that just has the adaptive-cycle feature, but it really is a full-up engine that has all of the suite of technologies that are being matured for these next-generation propulsion systems.”

The General Electric ADVENT engine has an adaptive-fan, which creates a third stream of air, an extremely high-pressure compressor, a new combustion system, various new materials such as ceramic matrix composites and cooling technologies, McCormick said.

In testing, the General Electric ADVENT design’s core engine temperature exceeded its goal by more than 130 degrees Fahrenheit. According to the company, the engine set a record for the highest combined compressor and turbine temperature in the history of jet engine propulsion as validated by AFRL.

Further, McCormick said that the ADVENT demonstrator engine is actually exceeding expectations in many cases including for fuel burn. The fuel efficiency target for ADVENT was to reduce fuel-burn by 25 percent.

The AFRL’s follow-on Adaptive Engine Technology Development (AETD) program is intended to bring the technologies developed under ADVENT into a flight-worthy design. ADVENT was primarily aimed at proving that a working adaptive-cycle engine is feasible. Engineers did not take into account the weight, size or other factors that would enable the engine to physically fit into an operational aircraft.

“AETD is taking that suite of technologies that ADVENT is bringing forward and maturing and now looking at how those get packaged into designs we could physically fit into airplanes,” McCormick said.

But AETD is not a direct continuation of the ADVENT effort. The Air Force held a fresh competition for the follow-on program, and in the end General Electric and Pratt & Whitney prevailed while Rolls-Royce was knocked out of contention.

Unlike the ADVENT program, the AETD effort will not produce a complete engine.

Preliminary designs

However, the companies are required to take a complete engine design to a preliminary design review (PDR). Originally that PDR was scheduled for November 2014, but the Air Force encouraged General Electric and Pratt & Whitney to push it back to February 2015.

There were two reasons to push the PDR back. One major reason is that the NextGen follow-on to AETD may not start until fiscal year 2016.

“That’s a FY16 start, and so by moving the preliminary design review milestone a little bit to the right, that helps us with levelizing the manpower,” McCormick said.

“The second reason is that AFRL was interest and in fact encouraged us to move it to the right to better align with the current preliminary design review schedule of our competitor.”

For the AETD program, there are two phases of testing. The first phase includes several combustor rigs—one of which is a full annular combustor. Additionally, General Electric is will test an exhaust system integration rig and components using CMCs, all of which should be completed by early 2015.

“We have testing going on as we speak primarily in the combustor area,” McCormick said.

“In fact we are on our third separate combustor design—combustor rig test plan. We also have an upcoming nozzle test that we’ll be running over at NASA in Cleveland [Ohio] here over the summer.”

The second phase of testing includes a fan rig, a compressor rig, and a core engine test. The General Electric plans to test the fan and compressor in late 2015 and early 2016 before the finale in late 2016 with the core engine test.

“There is no full-up engine test in AETD,” McCormick said. “There was no requirement or need to do a full-up engine test for us in AETD.”

Following AETD, the next step towards an operational adaptive-cycle engine is the Air Force NextGen program. Earlier in the year, Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel announced that there would be $1 billion invested into bringing an advanced engine into production. However, at present there are few details available on exactly how development will proceed.