Punk rock is no stranger violent politics. From decrying statist militarism to embracing revolutionary upheaval to reveling in the nihilistic specter of nuclear war, the genre has a lot to say about conflict.

Name any war, police action, popular unrest, and there’s a good chance somebody sang, shouted, screamed or spat about it to a crowd

The scale of irregular violence surrounding the better known clashes between Cold War superpowers is staggering. U.K. post-punk band Gang of Four memorialized the omnipresence of irregular conflicts in the 1979 song 5.45, emphatically declaring: “guerrilla war struggle is a new entertainment.” Many of their contemporaries seemed to agree.

The list below is far from comprehensive (you could write a dissertation about Vietnam’s role in American punk rock) but it reflects a cross-section of the geography and strategy of the Cold War’s irregular conflicts.

Clandestine Violence in the Anti-Communist World

The most immediate battlefield of superpower ideologies for many living in the West was not full-blown civil war, but the internal conflict between revolutionary cells and their capitalist governments. For many groups in the West committed to revolutionary change, terrorism or spectacular violence to highlight oppression (or mobilize class revolt) was the strategy of choice.

Without a popular base and facing sophisticated opposition, groups such as Germany’s Red Army Faction and Italy’s Red Brigades abandoned more mainstream (and peaceful) protest and party movements and went underground. Cut off from wider leftist politics by the requirements of operational security and the consequences of its violence, urbanized, underground terror adopted the rural and anticolonial strategies of Mao, Guevara, and Fanon for the West’s metropolitan core.

Germany’s Red Army Faction (RAF, also known as the Baader-Meinhof group or gang)—along with its more prolific, but less publicized Revolutionary Cells (RZ)—attempted a new way forward after German student protests against the rise of West German conservatism and galvanizing incidents of repression such as the shooting of Benno Ohnesburg.

Fearing the re-Nazification of state security and lamenting the setbacks of peaceful protests, German radicals—with support from East Germany—drew on the ideas of Uruguay’s Tupamaros guerrillas and trained with Palestinian militant groups to begin terrorist attacks in West Germany in the early 1970s.

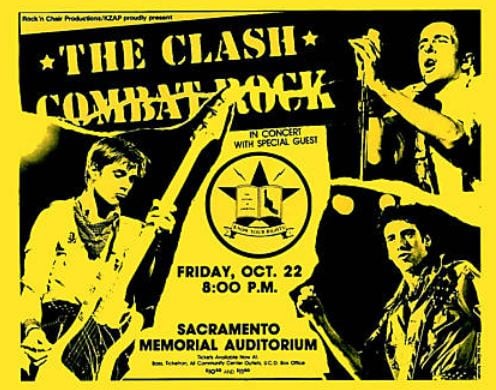

The aesthetics of the urban guerrilla had some natural appeal in the alienated, anti-authoritarian urban politics of punk rock. The Clash’s Joe Strummer made the RAF logo into counterculture chic, and the New Wave’s more apolitical Talking Heads channeled the mystique of the loner guerrilla in the big city in their hit, “Life During Wartime.”

The arrest and trial of RAF members in the mid-1970s prompted new dangers within Germany and to German embassies from the group and their allies such as the anarchist Movement 2 June. In 1977, the assassination of German prosecutor Siegfried Buback prompted a wave of attacks now called the “German Autumn.” RAF failed to kidnap of Jurgen Ponto, RAF members Hanns Martin Schleyer, a former Nazi industrialist, to force the release of the first-generation members under trial.

A potent symbol in that kidnapping – the baby carriage RAF members used to force Schleyer’s car to stop – ended up on the cover of German punk band S.Y.P.H.’s 1979 EP Viel Feind, Viel Ehr. Superimposing a fascist-favored slogan with a symbol of RAF terror, S.Y.P.H., like many German punks, felt the Swastika and RAF submachine gun “both unleashed the same reaction” on the street: “Complete disruption” and an unsatisfactory binary of terror and repression.

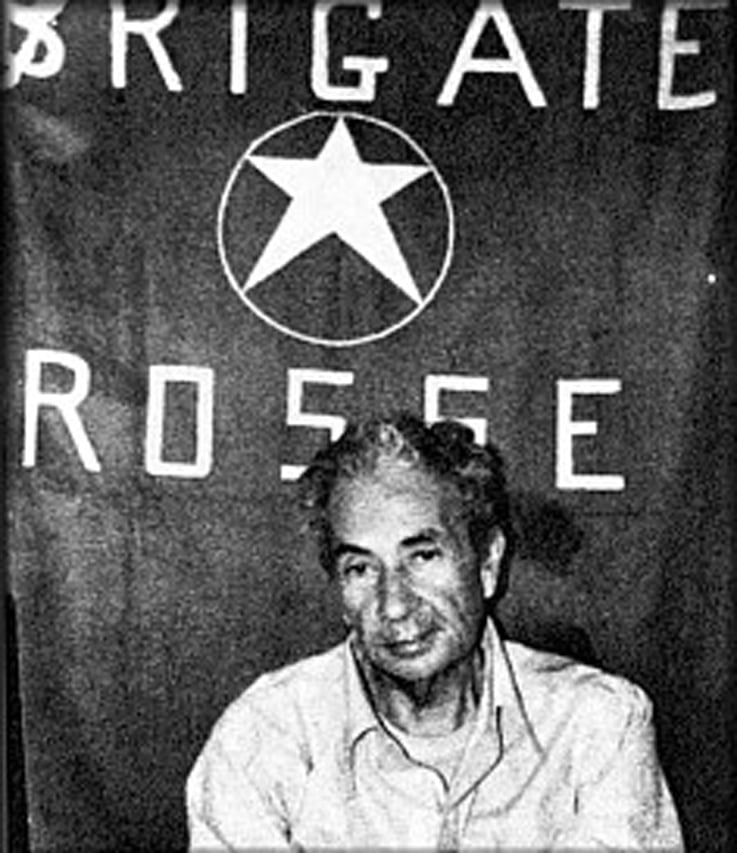

U.K.’s Crisis saw a similar problem with Italy’s Red Brigades (Brigate Rossi or BR), and was much more direct in their addressing of it.

Crisis sympathized with the BR’s leftist politics while noting their spectacular 1978 kidnapping of Aldo Moro revitalized the rationale and popular support for the security services of Christian Democrat-governed Italy and stoked the fires of the Italian far-right, whose own formidable terrorist factions long waged brutal campaigns of their own (often with government manipulation to put the blame on left-wing groups).

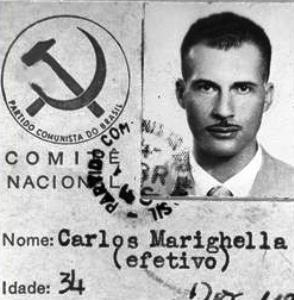

Some Brazilian bands — such as Legião Urbana—saw a similar fascination with violence of Europe’s clandestine militants since Brazil’s radical left pioneered urban militancy. Carlos Marighella’s Mini-Manual for the Urban Guerrilla inspired Brazil’s own clandestine insurgencies against the 1964 military dictatorship and similar groups around the world. Marighella, whose communist politics had him tortured by the police, expelled from the legislature and then shot in the wake of the 1964 coup, created a clandestine splinter faction, the Ação Libertadora Nacional (ALN).

Together with groups such as Movimento Revolucionário 8 de Outubro (MR8), Marighella and fellow communists who rejected the Brazilian party resistance to shun violence staged kidnappings of diplomats (including a U.S. ambassador), assassinations and bank robberies. Marighella was unabashed about the means this would involve: “Terrorism is an arm the revolution can never relinquish.” The police killed him in an ambush in 1969.

By the late 1970s and early 1980s enthusiasm and capacity for armed resistance faltered, and Brazilian military leaders Ernesto Geisel and João Figueiredo made moves toward relinquishing dictatorship. Nevertheless, urban terrorism and the dirty-war tactics of military repression left deep impressions on Brazil, the underground music scene of São Paulo. Law enforcement officers, acting through the paramilitary Esquadrão da Morte(literally, “death squad”) targeted enemies of the state and engaged in criminal activity

During the period, the Paulista punk and post-punk music began to thrive. Ratos de Porão’s U.K. hardcore-influenced 1983 debut, Crucificados pelo sistema, spoke to realities of urban violence and authoritarianism in the songs Guerra Desumana and Agressão/Repressão.In the late 1970s the political component of the violence gave way to criminality. Well-armed organized criminals such as Comando Vermelho would soon outstrip the revolutionaries’ violence and control of Brazil’s marginalized favelas. (The gang rivalries of the Paulista underground scene themselves would lead to Ratos de Porão’s initial breakup).

The Troubles

The Official and Provisional Irish Republican Army’s aims of dismantling the U.K.’s rule over Northern Ireland long predated the leftist terrorism that came to define much of the era’s conflict, but the combatants—along with musicians—exerted profound influence on imitators around the world.

The late 1960s saw the frustration of peaceful attempts by nationalist groups for reform and loyalist paramilitary groups such as the Ulster Volunteer Force’s targeting of Catholic civilians and IRA members. The conflict heightened in 1969 as the Royal Ulster Constabulary proved unable to clamp down on paramilitary activity or general disorder.

Belfast’s Stiff Little Fingers formed roughly a decade after the beginning of the so-called Troubles. By then the Provisional Irish Republican Army led the nationalist cause and the emergency deployment of army troops was an everyday reality.

Stiff Little Fingers was anti-authority and a harsh critic of government and security policy in Northern Ireland, but it was not made up of IRA supporters. Anti-authoritarianism extended to PIRA’s militarism as much as it did RUC and Royal Army control, as songs such as Alternative Ulster and Wasted Life made clear. When Stiff Little Fingers put out Suspect Device in 1978, it repackaged the terms associated with improvised explosive devices into an anthem for free thought.

American support for Irish nationalist causes was nothing new, but in the 20th century, America’s Irish republican supporters had access not only to money but also to weapons, as Gang of Four highlighted in their song about the conflict’s iconic Armalite Rifle. Belfast’s Ruefrex, in The Wild Colonial Boy, offered a withering critique of the Americans whose assumption of the Irish republican cause caused misery in Northern Ireland. Alongside their 1980s arch-enemy Moammar Gadhafi, Americans were among leading foreign backers of the PIRA.

Ruefrex’s criticism of Americans whose sense of Irish nationalism furthered stereotypes about bellicosity and thuggery while engaging in ethnic oppression at home was not a mere construct. For example, Whitey Bulger, infamous organized crime figure and violent opponent of busing, is proud of his support of the PIRA and helped smuggle several tons of arms and munitions to Northern Ireland.

Another tool Irish republicans wielded against the U.K. was the hunger strike, first made a prominent feature of IRA prison resistance after the Easter Rising and upsurge in revolutionary activity. A Derry group, the Undertones, alluded to hunger strikes in their uncannily poppy It’s Going to Happen, written during the winter of 1980. During the Troubles, PIRA prisoners in HM Prison Maze wanted to be treated as prisoners of war—a status the government changed in 1976.

The change allowed PIRA to maintain structure and cohesion within the prison system. After protesting prison uniforms with blankets and smearing their cells with excrement, PIRA prisoners turned to hunger strikes in 1980 and again in 1981. By this time, the Anti H-Block coalition had gained significant political prominence, to the point where hunger striker and former PIRA commanding officer Bobby Sands won election to the House of Commons. Sands, along with nine others, would die during the course of the strike; dozens suffered lasting injury.

Then-Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s refusal to cave into prisoner demands energized republican sympathies among many Irish Catholics worldwide. The Undertones, whose discography in 1981 was apolitical, even went so far as to wear black armbands during their 1981 Top of the Pops appearance in response.

Small Wars, Insurgency and Proxy Combat

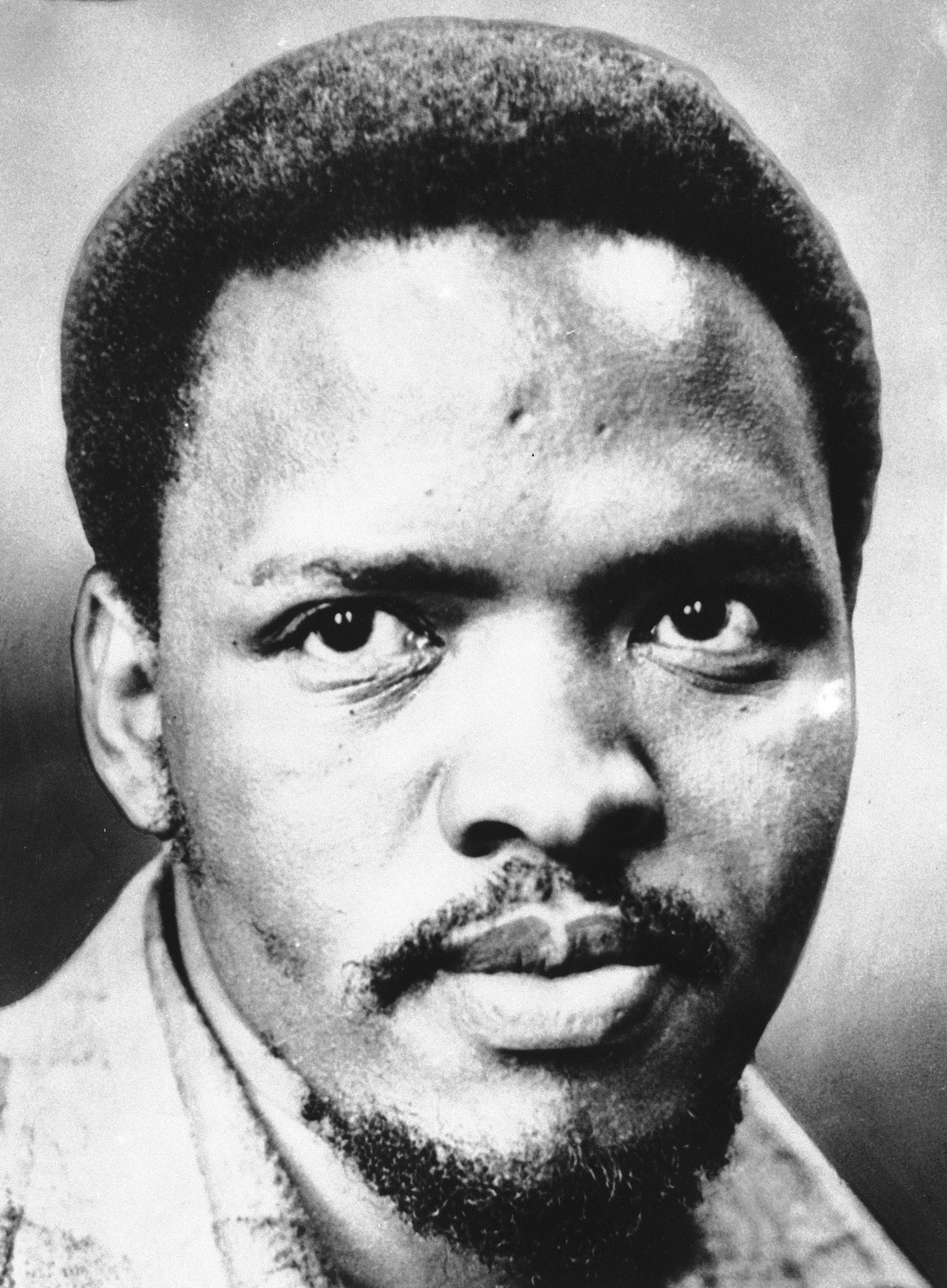

The white supremacist governments of apartheid South Africa and Rhodesia waged dual campaigns throughout the Cold War. Their domestic policies of racial oppression stoked discontent and an opportunity for the revolutionary left. Simultaneously, the colonial control in sub-Saharan Africa left South Africa and Rhodesia potentially surrounded by a hostile government. In 1976, mandatory Afrikaans educations prompted demonstrations in Soweto and bloody government repression. In 1977 Black Consciousness Movement leader Steve Biko died in prison.

National Wake—a biracial band whose two black members were among those the government forced to settle in Soweto—formed in 1978. Fusing Anglo-American punk and Caribbean reggae, National Wake’s very existence—let alone its lyrical content—was a subversive threat to the South African status quo. After years of struggling to get along in a scene that could not escape segregated venues and police intimidation, National Wake put out just one album before cracking under the pressure. In a coercive and perverse example of the “sell out” dilemma many punk bands faced at this time, a policeman cynically suggested that they could make more money as a band playing in exile.

One track too controversial to make it to the record was called Mercenaries. The band’s subject, the “dogs of war” who travel to a foreign land out of greed or even just sheer boredom, provide a more violent counterpoint to the consumer of guerrilla conflict news in Gang of Four’s 5.45.

Expatriates and fortune-seekers are a fixture of pop culture’s views of sub-Saharan African conflicts (just ask Warren Zevon), and for good reason. British veteran Mike Hoare and French veteran Bob Denard, and a host of other hired guns waged wars where their patrons in the West had to limit direct involvement and uncomfortable partners such as South Africa needed the help. Denard had waged multiple wars on multiple sides in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and did not let a head wound from a firefight with a North Korean detachment there keep him from fighting other wars in the region or a botched coup attempt in Benin in 1977.

In 1978, he overthrew the government of the Comoros with Rhodesian and Western support, a task that would become his specialty. His activities there allowed his outfit and interested powers to discreetly maintain trade with South Africa in the face of sanctions, as well as to support guerrilla wars in other theaters in sub-Saharan Africa.

White volunteers from the United States, France and other states operated in Rhodesia’s bush war, and mercenaries (alongside more formal efforts by Western intelligence agencies) played significant roles in Mozambique and Angola, where they came up against foreign support, on the communist side, the preferred factions of China, the Soviet Union, North Korea and a significant direct military presence by Cuba.

A South African band drawing on post-punk and experimental sounds in the late 1980s, Koos, also played up the paranoia of the intersection between a worldwide Cold War, South Africa’s regional violence and the more mundane globalization of culture in Is Jy ‘n Moegoe.

Peru’s subte punk scene in the 1980s was emblematic of grappling with the consequences of insurgent revolution. Peru’s underground music had pioneered proto-punk and rock sounds in the 1960s and 1970s. The 1980s scene came at a time of political turmoil after a succession of civilian and military regimes. In the rural areas surrounding Ayacucho, Abimael Guzmán was building Maoist cadres.

The Shining Path responded to 1980 elections by destroying ballot boxes and hanging dogs on streetlamps with placards condemning Chinese reformist Deng Xiaoping as a warning to rival leftist factions. By 1982, the Peruvian military had declared martial law and enlisted the rural rondas to provide a militia response to the growing uprising. The result was abusive counterinsurgency and unapologetic massacres from the Shining Path.

Lima’s Ataque Frontal (formerly Guerrilla Urbana) chose for its 1987 self-titled recording an image from the military-coordinated rondas‘ massacre of 8 journalists in the village of Uchurraccay. It was a radically anarchist band, and consequently accepted neither the ideological premises of contemporary combatants nor the violence of their means.

The opener declared the basic mission of any civilian caught in a conflict: Sobreviviré. They, and many other Peruvian punk rockers, offered a striking contrast to foreigners such as Rage Against the Machine’s Tom Morello, who as late as the 1990s lionized the Shining Path as martyrs of Peru.

For Ataque Frontal and others, though, the contemporary insurgency was not merely a matter of political posturing or public image. Nevertheless, as in many aspects of civil war documentation, the urban-rural divide mattered. Though bands such as Kaos wrote songs about Ayacucho, few of these Lima bands played shows in the region itself in the 1980s. One exception, Eutanasia, played a show there in 1987—one that some soldiers hailing from the band’s Lima hometown even attended in a search for respite from their duties in the war-torn region, despite the band’s anarchist and anti-government outlook.

In Lima Shining Path sympathizers attempted to get Peruvian punks to take up militarized resistance. Peru’s counterterrorism units detained and tortured underground musicians such as feminist punk Maria Teta. A few members of the scene responded to government coercion and insurgent subversion with their own radicalization. For example, a flautist for one subte band, Seres Van, died engaging Peruvian National Police’s “SUAT” unit.

Fliers circulated at concerts and police batons broke them up. Songs such as Narcosis’s Sucio Policía made clear, there was no love lost between musicians and a repressive government. Even though the Shining Path could stage terrorist attacks on Lima and stoke military repression, efforts to convert the subte proceeded neither to revolutionary satisfaction nor more mainstream society’s suspicion.

Even so, the daily potential violence from both government and insurgent (whose victory by the end of the Cold War seemed to many still plausible) provided a sort of microcosm of the inherent guerrilla war dilemma of insurgent choice. In conflicts where committed belligerents and collaborators often fare better than uncommitted civilians, the decision to stand apart bears significant weight.

Conflicts in El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala and the Contra counterrevolutionary movement against the Marxist Sandinistas in Nicaragua, fueled music often told from Anglophone and European perspectives.

Joe Strummer’s affinity for groups such as the Sandinistas was no secret. He was no anomaly. The Ex, from the Netherlands, explicitly stated in War Is Over (Weapons for El Salvador) that “guerrilla war is not the problem, it’s the bloody solution.” Sleeping Dogs, an American band on Crass Records, recorded (I Got My Tan In) El Salvador in 1982 in reference to U.S.-backed counterinsurgency campaigns in Central America while contrasting them with the luxurious tropical paradise available to those who could enjoy those countries from the highest social tiers.

The United Kingdom’s Insane wrote their own condemnation of U.S. policy in El Salvador in the same year.

For the intervening foreign power, El Salvador occupies a controversial place in the history of counterinsurgency operations. After Gen. Carlos Humberto Romero secured a 1977 election with rigging and violent intimidation, government repression, including death squads, a term the war would give morbid infamy, claimed thousands of lives by 1980.

In response, a reformist junta deposed the general in an attempt to stabilize the country. However, unwillingness of the military and hardline civilians renewed violent repression. Human rights-sympathist Jimmy Carter continued military aid despite thousands of casualties in 1980 alone.

Revolutionary guerrilla groups coalesced under the banner of the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) and launched major offensives in 1981, and the war would continue until its legitimization as a political party in the 1992 Chapultepec Peace Accords. Thousands died and a million became displaced or refugees.

For some in the United States, El Salvador was still something of a model. U.S. personnel trained and advised local forces, and managed to improve their capacity and rein in some of the military’s excesses (something even a FMLN commander admitted).

Measured against the overpowering fear of a new Vietnam in Central America, the circumscribed role made even a dozen year long conflict filled with atrocious conflict seem further from the worst possible outcome. That anxiety weighed on both military planners fearing escalation and young people fearing a draft. Nevertheless, that the war only ended after the collapse of the communist bloc, huge civilian casualties, and a U.S. strategy that traded direct action for complicity in its client’s abuse.

Interestingly, although El Salvador and other U.S. involvement in guerrilla wars across Central America is often remembered along with U.S. support for the Afghan mujahedin as an uncomfortable consequence of proxy warfare, many punk rockers were openly enthusiastic about the insurgent struggle against the Soviets.

The Ejected, an Oi! band best known for a song criticizing people who panhandled at concerts, declared “We should be giving guns to the Afghan rebels” in 1984. The Angelic Upstarts, known for their working-class leftism, wrote Guns for the Afghan Rebels earlier in 1981, offering only a slightly less emphatic defense of the ultimate downtrodden underdog, the Afghan mujahedin who had been resisting a direct Soviet invasion since 1979. Even the Clash, whose Washington Bullets was largely a condemnation of Western anti-communist proxy warfare, gave a verse condemning the Soviet invasion alongside Chinese treatment of Tibet.