The Navy has already made some powerful assumptions about its next fight in the air.

It’ll be away from home. It will be against a sophisticated and well-armed enemy. It’ll depend as much on information technology as it will on bombs or missiles. And it’s a fight for which the service isn’t ready.

When Adm. Jonathan Greenert—the current Chief of Naval Operations—took over the service in 2011, he laid out three basic tenets to sailors and all the ships at sea: “War Fighting. Operate Forward. Be Ready.”

The subtext was clear; the service had spent more than a decade supporting the fight in Afghanistan and Iraq, and as a result, its capability to fight a high-end war at sea and in the air had degraded.

The might of the U.S. carrier fleet was used to drop bombs on Taliban fighters and others that did not have the benefit of high technology anti-air weapons.

The United States easily dominated the battlefield, but has realized in the past few years the next air war won’t be nearly as easy.

“You want power ashore? We can push power ashore from the Navy,” Rear Adm. Thomas Rowden, director of surface warfare (N96) for the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations (OPNAV) told USNI News in an interview in the Pentagon on 9 January. “Other potential adversaries have taken note of our unfettered access—which has given rise recently to this term: anti-access/area denial” [A2/AD].

A2/AD is the modern twist on ancient strategies to deny adversaries access to territories. Tactics based on moats and ramparts have evolved over time into strategies based on increasingly inexpensive guided weapons that produce the effect of keeping enemies at a distance.

To counter the A2/AD threats of the future, the Navy is developing a new way to fight in the air that will depend as much on communications networks as it will on advanced weaponry.

NIFC-CA

That task falls to Rear Adm. Mike Manazir, OPNAV’s director of air warfare (N98), who currently is charting the way ahead and outlining the requirements for the Navy’s air arm into the 2020s.

The heart of the new plan is a concept known as Naval Integrated Fire Control-Counter Air—or NIFC-CA (pronounced: nif-kah).

The central tenets behind NIFC-CA are situational awareness and extended-range cooperative targeting.

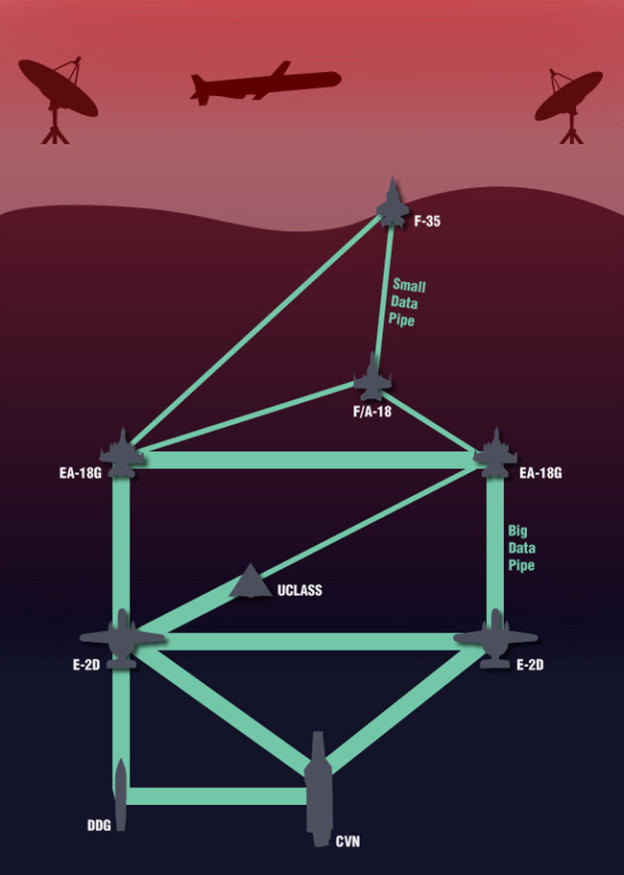

Every unit within the carrier strike group—in the air, on the surface, or under water—would be networked through a series of existing and planned datalinks so the carrier strike group commander has as clear a picture as possible of the battle-space.

“We’ll be able to show a common picture to everybody,” Manazir told USNI News during a 20 December interview. “And now the decision-maker can be in more places than before.”

Many of the capabilities envisioned for NIFC-CA already exist on board the Navy’s carrier fleet, Manazir said.

But the existing capabilities will evolve in the late teens and early 2020s into a seamless network that will allow for far better situational awareness and for much more precise command and control over hundreds of miles.

Effects, Not Platforms

Beyond situational awareness, NIFC-CA forces naval planners to think creatively about the capabilities of individual platforms within the carrier air wing or even the carrier strike group at large. Under NIFC-CA, the sum of a carrier strike group’s firepower has to be considered in aggregate.

For example, targets spotted hundreds of miles away by one sensor—such as the emerging F-35C Lighting II Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) or E-2D Advanced Hawkeye intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) aircraft—could be engaged cooperatively by any number of shooters: a JSF, F/A-18 E/F Super Hornet tactical fighter, or future unmanned vehicles, all available to the strike group over vast distances.

The attacking aircraft could cooperate with Arleigh Burke-class (DDG-51) destroyers and even submarines working together as a coherent whole—connected via data-links—under the NIFC-CA construct.

With the shared data, the effectiveness of each component in the NIFC-CA web can do more and see more.

“In the past, we bought platforms for platform capabilities,” Manazir said. “Really what we’re buying now, is we’re buying integrated capability to deliver an effect on the maritime battlefield.”

Sensors and Shooters

An example cited by Manazir is how a carrier strike group operating inside an anti-access environment would launch a strike deep into heavily defended hostile territory.

Under NIFC-CA, the carrier air wing would launch all its aircraft, Manazir said. But the stealthy F-35C’s role would be to fly deep into the heart of hostile airspace to gather ISR data.

The F-35C itself would be supported by stand-off jamming from the EA-18G Growler with next generation jammers—and possibly other capabilities—to degrade enemy low-frequency early warning radars in order to help facilitate its penetrating ISR mission.

Potentially, in the future, the Navy’s forthcoming unmanned carrier launched airborne surveillance and strike (UCLASS) aircraft could be used to extend the range of the F-35C via aerial refueling and supplement its ISR capabilities.

But at its core, the idea would be for the F-35C to use its extensive array of sensors to find and identify targets. “What’s in the F-35C can give us a weapons-quality track that we can push back to the E-2D,” Manazir said.

The E-2D Hawkeye—which coordinates the carrier strike group’s air assets—would then send the data from the F-35C to the air wing’s Super Hornet strike fighters.

The weapons-laden F/A-18E/Fs would then penetrate as far as possible into the heavily defended zone before launching their stand-off weapons in a coordinated effort. And like the F-35C, the Super Hornets could also be refueled en route by the UCLASS.

“That F/A-18E/F can push to the limits of its stealth technology as well,” Manazir said. “People think the F/A-18E/F is a fourth-generation fighter—can’t get close. That’s not true; the treatments that Boeing and PMA-265 at Pax [Patuxent River, Md.] have done to that airplane are such that we can get close in enough to be effective with the weapons we’re going to have on the airplanes here relatively soon.”

Effectively, that would realize the maximum shooting range of the Navy’s forthcoming long-range weapons—which can go further than a shooter can see.

Manazir said that the Navy is working on a number of weapons that are both longer-ranged and far more survivable than ones currently has in its inventory.

“We need to find ways to take our weapons and make them more survivable in the higher-end threat anti-access environment,” Manazir said. “And we’re doing all of that.”

Once the Super Hornets launch their standoff weapons, those missiles are guided by a data-stream from the E-2D, Manazir said. Toward the latter stages of the missiles’ flight, the F-35C would take-over guidance of the weapons for the end game. “It can give the weapon an updated location and where to go to that target,” Manazir said.

Rise of the Data-Links

The key challenges for NIFC-CA will be data-links. Every aircraft is connected to every other aircraft in the carrier air wing via the E-2D, which acts as a central node. The E-2D is also connected to the carrier and the rest of the strike group—making that aircraft a crucial asset for future naval fires. Effectively, with NIFC-CA, the carrier strike group would be able to cover hundreds of miles of territory with weapons and sensors.

The Navy has worked over the past half-decade to develop the necessary data-link technology to implement the ambitious NIFC-CA plan.

“Over the past five years we’ve finally matured the lightning bolts to be able to that,” Manazir said. “That’s what was missing in the past, that’s why we had these very high-end weapon systems like the F/A-18Es and Fs Block II with the AESA [active electronically scanned array] radars with all of this fusion on there and fusion systems that would do their own track.”

But with the development of the Rockwell Collins-designed tactical targeting network technology (TTNT) waveform, an individual platform does not necessarily need to generate its own tracks.

“Now with TTNT in our MIDS-JTRS [multifunctional information distribution system joint tactical radio system] radios, you’re able to move that data back and forth,” Manazir said. “Now I can bring that whole integrated architecture to the fight to deliver whatever effect I want to.”

The TTNT waveform allows for very high data rates and has very low latency, making it ideal for sharing vast amounts of data over long distances, as was demonstrated during the Joint Expeditionary Force Experiment in 2008 at Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada.

For the purposes of NIFC-CA, the TTNT would link together the carrier strike group’s E-2Ds, EA-18Gs, the carrier itself and eventually the UCLASS.

“The two E-2s would be on this TTNT network and it would share the whole picture,” Manazir said.

The E-2Ds would share a specific part of their data with the EA-18G Growlers, which would also be linked via a TTNT network or potentially a variant of the Link-16 data-link, Manazir said. If the Growlers do end up using the Link-16, the EA-18G would use an advanced variant called concurrent multi-netting-4 (CMN-4), which is basically multiple Link-16s “stacked up” on top of each other. “If you have four radio receivers, you can move that data,” Manazir said.

The Growlers would coordinate with each other using their data-links to precisely locate threat radar emitters on land or on the ocean surface using a technique called time distance of arrival. “They can locate that down to enough of an ellipse where we can put a weapon onto that ellipse,” Manazir said.

Moreover, the data-link coordinated Growlers could also use the same technique to eliminate hostile electronic warfare assets that might attempt to attack the NIFC-CA battle network. “When we widely disperse sensors, like two E-2s or two Growlers, the threat—you can’t jam all of that,” Manazir said. “If one guy is getting jammed real hard, the other system over here can see . . . we not only home in on the jamming, but we can see where the energy is coming from and then we can actually target whatever it is.”

To eliminate the target once it is located—in the air, on land, or floating on the ocean—the Growlers or the E-2D would relay via Link-16 a “weapons quality” track to one of the Super Hornets, which would actually destroy the threat.

“That F/A-18E/F and the F-35C out front, they don’t even need to have their radars on,” Manazir said. “They don’t need to be contributing to the picture themselves, they are just receiving this data.”

Moreover, the F/A-18E/F would not even necessary even control the weapon that it launches—other than pulling the trigger. The E-2D, the EA-18G or even another Hornet or F-35C could guide that weapon, Manazir said.

The Networked Downside

But while networks are the great strength of the NIFC-CA concept, they are also a source of vulnerability. Particularly, for the F-35C, which the Navy plans to use as a long-range penetrating ISR platform, it needs a secure and low probability of intercept data-link to relay information back to the fleet.

“We need to have that link capability that the enemy can’t find and then it can’t jam,” Manazir said. “The links are our Achilles’ heel, and they always have been. And so protection of links is one of our key attributes.”

The NIFC-CA network will be built with redundancy so that the fleet can continue to operate while under electronic or cyber attack.

“It is very difficult to jam links across a broad geographic area,” Manazir said. “If you’re going to take out our eyes completely, you [have to] take out space.”

China, for example, has demonstrated the ability to destroy orbiting satellites, and has its own array of cyber and electronic warfare capabilities. Realizing that such an attack could be possible, the Navy has developed ways to mitigate for the loss of space-based communications.

“We have those mitigation efforts built into our weapon systems so that you can create a line-of-sight network,” Manazir said.

More Challenges

However, as promising as the NIFC-CA construct sounds, it is an extremely ambitious effort and there are still potential wrinkles.

One of the major concerns raised by a number of operational aviators consulted by USNI News is the potential over-reliance on networks.

As one highly experienced pilot pointed out, even if the NIFC-CA network is large enough that the whole system cannot be jammed at any one time, that does not mean individual strands of the web cannot be cut.

Even if just some individual elements of the NIFC-CA network are disrupted, it could seriously effect data distribution, he said.

Another point that the aviators raised was that while the common picture afforded by NIFC-CA allows for many advantages, it could also open the door for senior leadership to “micro-manage” tactical decisions from afar.

Senior leaders will have to consciously stop themselves from getting over involved in tactical execution—or risk disaster. “That’s a reality of airpower,” one pilot said.

U.S. Air Force officials consulted by USNI News applauded the NIFC-CA concept. That being said, those officials expressed their concern that the Navy does not appear to have addressed cooperation with the Air Force against an A2/AD threat under the NIFC-CA construct. The two services are supposed to be working together closely under the Pentagon’s Air Sea Battle concept.

Cooperation with the Air Force may come later as the NIFC-CA concept begins to mature. NIFC-CA itself is only one segment of the overall NIFC concept. The Navy has plans for sea and land-based elements that together would form an overarching battle network. As the NIFC concept develops, time will tell if the Navy’s next steps for the next war are the right ones.