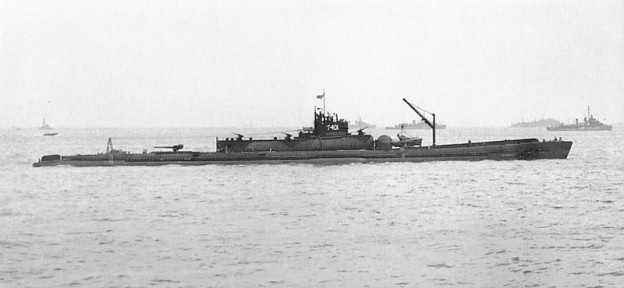

Last week the media around the world carried stories about the rediscovery of the Japanese super-submarine I-400. One of the more unique submarines of the past century—part aircraft carrier, part submarine—she inspired books, television documentaries, and a years-long quest to find exactly where it had come to rest in a postwar weapons test designed to keep it from Soviet eyes.

The discovery of I-400 was the result of the perseverance of Terry Kerby, Steve Price, and the team at the Hawaii Undersea Research Laboratory (HURL)—along with a small amount of funding from NOAA’s Office of Ocean Exploration and Research, and a convergence of opportunity.

It’s no secret that dwindling financial resources have reduced the missions of HURL, as well as other ocean research. In order to get research ships, submersibles, and robotic systems out to sea in the face of fewer government dollars to do so, missions these days are fewer, and they are tightly focused, collaborative, and smart.

On a recent (July 2013) mission to the Gulf of Mexico to examine an early 19th century shipwreck and its surrounding environment in 4,300 feet of water, a consortium of three federal agencies—NOAA (the Office of National Marine Sanctuaries and the Office of Ocean Exploration and Research), the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), and the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE)—joined with two state agencies (the Texas Historical Commission and the Maryland Historical Trust), and three not-for-profits (the Meadows Center for Water and the Environment, the Ocean Exploration Trust, and ExploreOcean) on a foundation and philanthropically funded expedition that cost taxpayers only the salary-time of the several federal scientists involved.

The mission discovered that the wreck is likely associated with the at-times violent transition from Spanish Empire to a multitude of independent nations. Significantly, it also may be the first privateer wreck yet found in association with its captured prizes, as the effort discovered two other ships lying nearby.

Analysis is ongoing, and more cannot be said—yet—but there is some confidence that the project will add to if not help rewrite gulf and American history. In doing so, the project also shared the process of exploration, discovery, deep ocean science, and history with thousands of online viewers as it happened.

HURL’s latest work continues in that tradition of making science happen while conducting test dives and combining expertise collaboratively in “cruises of opportunity.”

After refurbishing a purpose-built floating dock known as the LRT, which can be towed to sea by a tug, HURL’s aquanauts have been testing this cost-effective launch system (about a third of the cost of launching from a larger research vessel) with its veteran Pisces submersibles.

NOAA’s Office of Ocean Exploration and Research helped fund those transitional tests. As two senior NOAA scientists, Dr. Hans Van Tilburg and I were invited to make three dives to assess the new launch system and coincidently serve as archaeologists as Terry Kerby piloted Pisces V to look at some sonar contacts that he, Steve Price, and the team hoped might be as-yet undocumented historic shipwrecks. (Dr. Van Tilburg coordinates maritime heritage activities in the Pacific for the NOAA Maritime Heritage Program in the Office of National Marine Sanctuaries.)

Kerby and Price have a list of finds they’d like to make. Carefully having searched the archives, they know of a large number of vessels lost accidently or purposely scuttled off Oahu in Hawaii, as well as aircraft, among them wartime losses with unresolved questions about why they went down.

They also include famous vessels, like the just-discovered I-400.

By combining cruises of opportunity, such as test dives or television documentary-funded filming, they have made some amazing discoveries through the years, including two Japanese Type A midget submarines—one of them the boat sunk by the USS Ward (DD-139) in the opening hours of the attack on Pearl Harbor.

They also have found scuttled U.S. ships such as the submarine S-19 and lost aircraft, beginning with their first deep-sea maritime heritage find—an intact SBD Dauntless dive bomber—in 1984.

Among the scuttled Japanese submarines they have found prior to the I-400 are the captured I-14, I-201, and I-401. Along with their ongoing assessment of the deep sea environment—including a multiyear study of a deep-sea volcano, the discovery of deep-sea corals that may be among the world’s oldest living organisms, and their documentation of other marine ecosystems—such finds are cost-effective and highly efficient, representing a unique center of excellence and research that should be regarded as a national treasure.

The University of Hawaii’s Undersea Research Laboratory—its submersibles, ship, the LRT, and the team that operates them to provide a platform and the tools for ocean science—are a treasure because they find the means to keep probing the secrets of a part of the planet vital to our economy, our national security, and ultimately, to the survival of our species.

The oceans are the final frontier on this planet. They represent the source of more than half of the food humans consume, they are the engine that powers our weather, replenishes our oxygen, and a repository rich with resources such as deep-sea minerals, oil and gas.

The oceans and seas are the largest canvas on which the history of the world has played out, as the highway by which humanity spread across the globe in the past half millennium, the means by which a global economy was forged in the past two centuries, and as our largest battlefield and our largest cemetery. The seas are our greatest museum, as the discovery of I-400 again reminds us.

The seas are also fragile, and largely unknown and misunderstood. I believe that missions like those of the Pisces V and the dedication of professionals and scientists like those at the University of Hawaii and HURL are essential priorities for humanity. In exploration we not only learn more about our planet and our history—we are reminded of what we are capable of achieving.