As China builds a coast guard with ties to the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN), the quest for naval power becomes more complicated as the U.S. Navy shifts towards the Asia Pacific.

As China builds a coast guard with ties to the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN), the quest for naval power becomes more complicated as the U.S. Navy shifts towards the Asia Pacific.

Different from international norms, China’s coast guard (CCG) is led by Communist Party politics at the highest levels and includes a direct working relationship with the PLAN. As a rising naval power, this closely linked command-and-control structure creates flexibility and synchronization for naval operations in the East and South China Seas to protect territorial claims. The United States has an interest in reducing future maritime miscalculations in the Asia Pacific. That requires a grasp of Chinese political and military relationships, without which the probability for a clash may increase.

Most scholars, policymakers, and members of the national security community focus their attention on China’s hard naval power: military ships, submarines, weapons, and aircraft. To understand China’s developing naval strength, one also should examine the impact of China’s soft naval power—including civilian ships and aircraft involved in humanitarian, law enforcement, and ocean research operations. By combining hard and soft power elements, a nation can develop a robust naval presence having applications in peace or wartime.

The establishment of the CCG in March of this year supports a soft naval power approach to influence the East and South China Seas more effectively than any other nation in the Asia Pacific. China has been expanding its soft naval power for the past several years and could reach nearly 500 ships by 2020.

In the coming years, the number of CCG ships will also outpace Japan’s coast guard as well as those of other Asia Pacific nations. The number of ships alone does not assure sea control, but the large capacity of civilian-led ships provide a sustained presence to guard territorial claims and serve as intelligence nodes for military units. More important, CCG ships in an armed conflict complicate the battle space and could possibly force an adversary to pursue both CCG and PLAN ships simultaneously to achieve sea control.

The State Oceanic Administration (SOA) is instrumental in the growth of China’s naval power as the leader of China’s civilian maritime organizations, which includes the CCG. The CCG’s operations off Japan’s coast in July displayed a new ship-painting scheme and represented the first visual signal of an ongoing civilian ship buildup over the past several years. Until the establishment of the CCG, the SOA maintained the largest civilian fleet under the auspices of China Marine Surveillance (CMS) organization.

Every year since 2009, the PLAN and SOA have met to coordinate maritime issues and further develop China’s naval power. During this year’s annual meeting, the leaders of both expressed their ongoing working relationship and future goals. Liu Cigui, the SOA Director, outlined a six-point cooperation proposal indicating a requirement to “strengthen security cooperation in the military services.” Vice Admiral Ding Yiping, the PLAN deputy commander, outlined a four-point plan “to further deepen bilateral cooperation in law enforcement.”Ding and Liu were photographed together demonstrating the positive relationship between the two naval forces.

Notably, Ding was the senior officer this summer during the Sino-Russian naval exercise, which included 13 warships, three-fixed wing aircraft, and five ship-borne helicopters.

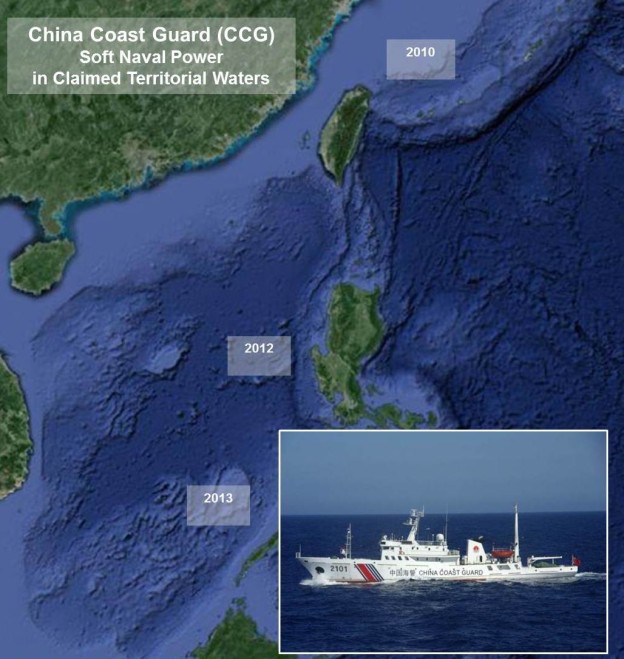

Three naval milestones point to a common trend about how China may address future maritime territorial issues. First, the CCG (formerly known as CMS) consistently operated in the vicinity of Senkaku or Daiyuo Islands, which in 2010 ultimately led to the collision at sea with a Japanese fishing vessel. Second, in 2012 the CCG began patrols near Scarborough Shoals to protect territorial claims, which resulted in a non-violent maritime engagement with the Philippines. Since January, the Philippines has been unsuccessful to influence a U.N. decision regarding the territorial dispute at Scarborough Shoals. Third, the CCG earlier this year began operating near Second Thomas Shoal approximately 500 miles southwest of Manila.

As illustrated in the East and South China Seas graphic, China is maximizing its soft naval power and expanding its naval reach in claimed territorial waters. This increased capability allows China to maintain presence and sustain operations in those waters without the use of hard naval power. In essence, China has instituted a “first-use policy” in which the CCG serves as the key arbitrator on the high seas. The CCG can monitor and protect national interests in the maritime domain without committing PLAN assets unless a situation warrants action. While the United States may have a qualitative advantage in an armed conflict, China has the leverage to manipulate and peacefully control the seas by deploying the CCG.

Compared with the CCG, the United States lacks a soft naval power in the Asia Pacific and a capability to de-escalate a territorial dispute in a nonthreatening manner. The U.S. Coast Guard has a plan to build 25 Offshore Patrol Cutters (OPC) that are equivalent to several CCG ships, but the first OPC may not be completed until 2020 and the entire 25-ship fleet will potentially not be delivered until the 2030 time period. Utilizing the Navy’s littoral combat ships, destroyers, or frigates against CCG ships only increases tensions in territorial disputes.

If tensions should escalate, the PLAN could quickly provide a forceful backup and create a seamless flow of naval assets. With a large number of ships scattered over a particular geographic area of operations, the CCG can establish a maritime picture and provide cueing for PLAN assets. Both the PLAN and SOA also consist of a North Fleet, East Fleet, and South Fleet. That geographical alignment promotes integration and a unified command if a contested struggle for territorial claims occurs.

Future of a National Fleet

The Chinese have made progress in the maritime domains (surface, air, subsurface) to acquire hard naval power, but have significant challenges in comparison with the U.S. Navy. While the PLAN continues to develop hard naval power elements, China will rely on soft naval power elements to protect its territorial claims and use the PLAN as required. By implementing a soft naval power and a “first-use policy,” China establishes a de-escalatory posture and creates an advantage for resolving conflicts at sea. Looking forward, U.S. political and military leaders should develop and fund a new national fleet strategy to meet the demand of China’s naval soft power in the Asia Pacific.

A national fleet strategy is not a new concept. In 1998, the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard established an interservice agreement to plan, acquire, and maintain forces.In 2006, both maritime services issued a joint policy statement to “deploy forces with greater agility, adaptability, and affordability across the full spectrum of conflict.” By 2007, the service chiefs from the Navy, Coast Guard, and Marine Corps signed the first combined maritime strategy, A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower.

This year the Navy and Coast Guard released an updated policy statement highlighting the requirement for integrated operations “from routine peacetime operations to crisis and sustained conflict.” Both maritime services also announced the organization of a National Fleet Board to develop a comprehensive National Fleet Plan by the end of the year charged with avoiding redundancies and achieving economies of scale given potentially scarce resources. Will that National Fleet Plan be similar to previous strategies or will it advocate a significant change for both services? Strategist Colin S. Gray concluded in 2001 that “the U.S. Navy and the Coast Guard are natural complements and that this complementarity should be expressed practically in a ‘national fleet’ that is not mere rhetoric.”

The National Fleet Board should promote a fleet with a balanced portfolio of hard and soft naval power elements. Naval historian and strategist Milan Vego, offers that “a Navy, no matter how strong, cannot carry out all the tasks alone, but needs to proceed in combination with other elements of naval power, such as a coast guard.” The U.S. Coast Guard has a vital role in homeland security, but also in global naval operations. The Navy should leverage future DOD funding toward creating a more comprehensive naval power that includes an increased Coast Guard presence in the Asia Pacific.

Three options may exist as policymakers explore possible solutions for a future national fleet and ways to counter China’s developing soft naval power. First, the United States could continue transitioning naval hard power toward the Asia Pacific, and increase political rhetoric in deterring the CCG from exploiting territorial claims. The U.S. Senate in late July passed a resolution condemning “the use of coercion, threats, or force by naval, maritime security, or fishing vessels and military or civilian aircraft in the South China Sea and the East China Sea to assert disputed maritime or territorial claims or alter the status quo.” Those types of political efforts establish a baseline for U.S. policy toward the region, but do little in influencing Chinese political and military leaders, given China’s naval presence in the disputed areas. China’s Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Hua Chun-ying swiftly responded after the Senate’s resolution by offering that it “sent the wrong message” and that China urged the Senate “to respect the facts and correct [its] mistakes so as not to make matters and the regional situation more complicated.”

Second, the United States could continue to sell naval ships to partners and allies in the region to increase friendly naval capacity in claimed territorial waters. The United States has sold two retired Coast Guard cutters to serve in the Philippine navy. Japan plans to deliver an unspecified number of ships to the Philippines later this year. On the surface, the idea of propping up navies in the region seems credible; however, those nations are so far behind in acquiring and maintaining ships—compared with China—that it will take decades, if not years to counter China’s advantage. Also, any future increases in foreign military sales to America’s Southeast Asia partners may fuel China’s desire for quickly advancing a naval buildup, creating additional tensions.

Third, the United States and Southeast Asian nations could expand the use of manned and unmanned aircraft to monitor claimed territorial waters. That option creates a robust unmanned fleet of aircraft operated by the U.S. Coast Guard as part of the National Fleet Plan. Increasing the number of aircraft generates a quick jump in soft naval power assets for maritime surveillance without tipping the scale toward escalation or miscalculation. Instead of regional allies investing in ships that cost millions to build and maintain, unmanned surveillance aircraft provide the necessary information to shape an area of operations and assist in decision-making. That option also further equips the U.S. Coast Guard to better patrol the U.S. mainland and enables the capability to deploy in the Asia Pacific as required.

As the United States enters a decade of reduced military spending and budget cuts, the decisions made by naval leaders and policymakers concerning a national fleet will be more important than ever. The goal in the Asia Pacific should be to avoid armed conflict and ensure the region remains peaceful, while at the same time, achieving U.S. economic and political objectives. Policymakers should examine China’s naval power holistically, including looking at how civilian and military assets can work together. With a focus on hard naval power elements as our nation shifts towards the Asia Pacific, and China’s continued pursuit of soft naval power elements aimed at protecting territorial claims, both nations could find themselves in a clash for naval power.