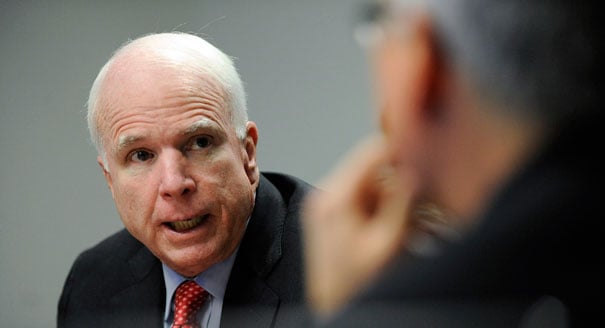

Sen. John McCain (R-AZ), a vocal advocate for more U.S. involvement in the Syrian conflict, is right about at least one thing—a victory for President Bashar al-Assad is a victory for his allies in Iran.

Sen. John McCain (R-AZ), a vocal advocate for more U.S. involvement in the Syrian conflict, is right about at least one thing—a victory for President Bashar al-Assad is a victory for his allies in Iran.

McCain is wrong on many other accounts, most notably the assumption that a more favorable outcome can be achieved if the United States plays a more heavy-handed role in the conflict: history shows that to be false.

McCain’s June comment on the floor of the U.S. Senate, “I have seen and been in conflicts where there was gradual escalation—they don’t win!” [sic], implies that America’s failure in Vietnam resulted from its escalatory strategic approach.

The impression he creates in his argument is that if the United States had gone into Vietnam hard and heavy from the onset, it would have achieved a more favorable outcome. It’s hard to imagine how one can categorize the massive investment in American blood and treasure in Vietnam as a light response. To suggest that a more robust—non-escalatory—U.S. strategy in Vietnam would have allowed the United States to achieve its objectives is at the very least a counter-factual argument.

Strategic failure in Vietnam can be attributed to many things, but perhaps most importantly it was failure to understand the nature of the war. We should be cautious not to make that same mistake again in Syria.

A better factual example to use when examining McCain’s notion that a robust involvement can create a better outcome in a complex environment is Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF).

OIF, in contrast to Vietnam, kicked off with a “Shock and Awe” no-holds-barred attack and an immediate ground invasion, destroying everything held dear to Saddam Hussein’s regime.

This was followed by a complete occupation of Iraq. Despite this U.S. effort, insurgent forces still found access to sufficient weapons to inflict a heavy cost on the American occupation forces.

At this juncture no one is suggesting that we put an occupation force in Syria, but the recent historical example of OIF serves to illustrate that no measure of American military power can assure a desired strategic outcome in a complex civil war such as that occurring in Syria.

A large U.S. commitment in Iraq resulted in what is at best a shaky strategic outcome, so why would any measure of force provide a different result in Syria? Finally, we are left to wonder, if neither a limited approach nor a full-blown occupation can assure a satisfactory outcome, then what should we do?

America can look to its own revolution for an example of how to respond to the civil war in Syria. Specifically, we can look to the role that France played in the U.S. war of independence.

“The first object of France was not to benefit America, but to injure England,” noted naval strategist and historian Alfred Thayer Mahan wrote.

What does America stand to gain for betting on the side of rebels? Here is where McCain is correct. The United States must be firm in insisting that Assad must go. The realpolitik view of this conflict suggests that a Sunni rebel victory has a better chance of creating a favorable outcome for U.S. interests in the region than an emboldened and Iranian-sponsored Shia regime under Assad.

Syria is a nation in the throes of a violent civil war that is clearly very different than that of the nascent American nation in the 18th century. Yet, the U.S. government and the Syrian rebels have one key objective in common: both wish to see the end of the Assad regime. France entered into an alliance with the American revolutionaries solely for the reason best expressed in crime-boss logic that the enemy of my enemy is my friend.

After all, the American idea of independence was as clear a threat to monarchial France then as rogue regimes with WMD are to the United States today. In short, the American Patriots and King Louis XVI’s government shared no cultural bonds or political ideology.

The French were not endorsing our anti-colonial independence movement; rather, they were acting in their own national interests.

Like France in 1778, the United States can gamble on the future of Syria by employing its might to blockade Syria’s coast, hinder the Syrian government forces, and assist Syrian rebels to remove Assad and his regime from power. The end result in Syria is likely to be less than satisfying for the United States, but in this case supporting the rebels is better than the alternative.