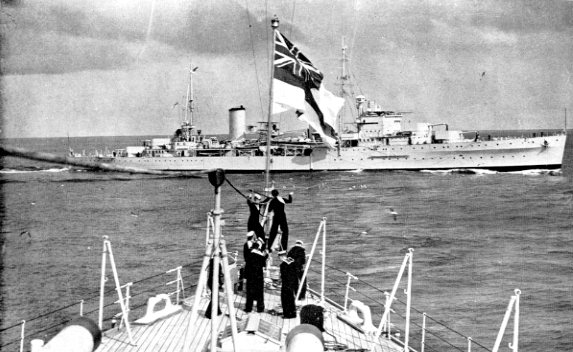

As more information comes in from the Sunday attack on Camp Bastion, Afghanistan more and more news outlets are calling the incursion of attackers dressed as U.S. Army soldiers as a “false flag,” attack. The term, originated in the maritime circles, referrers to a ship that flies a flag other than its own for military advantage. The following is a narrative from a false flag incident in World War II.

Proceedings, March 1953

On December 3, 1941, German Supreme Command announced: “An engagement has taken place fff the Australian coast between the German auxiliary cruiser Kormoran and the Australian cruiser Sydney. The German cruiser commanded by Fregattkapitan Detmers has defeated and sunk a much more heavily armed adversary. The 6,830-ton heavy cruiser Sydney went down with her entire complement of 42 officers and 603 men. As a result of the damage received in the fierce engagement, the Kormoran had to be abandoned after the victory.”

Behind this laconic statement is hidden one of the greatest dramas known to the annals of sea warfare. Two ships had fought a battle at close range, in which both were so severely damaged that within several hours one of them sank with all hands, leaving no trace, while the other was so badly burned that it had to be abandoned by its crew 140 nautical miles from the safety of land. It was not until 5 days later, when one of the Kormoran’s lifeboats reached the Australian coast, that the world learned what a great catastrophe had been enacted at sea. An air search was begun at once from western Australia, and on the tenth day after the action the exhausted crews of the Kormoran’s remaining lifeboats were saved by the Australian minesweeper, Yandra. Of the 400-man German crew, 300 were interned in Australian prison camps. We can only guess at the tragedies that occurred during these days and nights. The dead are silent, and we, the survivors, can only guess.

Nevertheless, the experiences of the survivors tell us that time can not only speed in its flight, but can also be frightfully long. Minutes become hours, and hours long days, and in a few days many a man becomes years older.

It is November 19, 1941- Rogation Day. The auxiliary cruiser Kormoran is following a course some 300 kilometers from western Australia. Everything is peaceful aboard, holiday routine. Only the mine crew is busy with its watch, going over the preparations for an attempt on the following night to approach the coast and mine the harbor of Freemantle.

It is 1500. The first officers to drop into the mess after an afternoon nap are relaxing over a cup of coffee or enjoying a leisurely smoke. Not much can happen; we are far out of the travelled shipping lanes, and aloft in the crow’s-nest a sharp sea lookout is scanning the horizon ready to warn us of any surprise.

Suddenly there is a call on deck; the bridge messenger bursts in and announces to the skipper: “Ship sighted to starboard!”

As the battle watch officer, I knew at once that I would spend the next hours on the bridge. I gulped down my cup of coffee (I little guessed that it would be my last for a long time!) and headed for my cabin to get my cap when the alarm bell clanged throughout the ship calling the crew to general quarters.

I hurried to the bridge, obtained data on course and speed from the officer of the watch underway, hung up my binoculars, and announced myself to the commanding officer as the battle watch officer.

From the bridge there was still nothing further to be learned about the enemy, though its running position had been announced from the crow’s-nest. From the speed with which the enemy was changing position, as well as by instinct, the Captain knew that this time he was not dealing with a merchant steamer. It was our task to destroy enemy shipping and not to engage in battle with superior fighting craft, for an armed merchantman can never be a match for a warship.

We changed course to turn away, and the fourth motor, our constant source of trouble during the entire cruise, was cut in, so as to escape at full speed before the enemy discovered us. The Kormoran had scarcely headed into her changed course when misfortune struck. The fourth motor had a Brandenburger (piston rod) worn out, and thick smoke streamed treacherously through the funnel.

From the mast comes the cry: “Enemy heading for us and approaching fast.” From the bridge the mast tips can be recognized. The crow’s-nest with the lookout are quickly taken down to avoid disclosing our identity.

Meanwhile we change course again, heading in the direction of the African coast. The enemy, which has been recognized as a cruiser, comes within range of our masked guns. We hoist the Dutch flag and stubbornly maintain our course. All hands are hidden under the deck; only the Captain and I are on the bridge. Slowly the Sydney approaches aft of our starboard. If she stays at this acute angle, we are lost, until we can come about and bring our artillery to bear. Verdammt! Now the propeller of the embarked plane is starting. If it takes off and flies over us, it will discover on the charthouse an artillery mount with fire-control apparatus covered by a tarpaulin.

The Sydney hoists a flag signal, “What ship?” in the international code. True to our role of merchant steamer we, as slowly and ceremoniously as possible, hoist the answer: “Straat Malakka.”

It is 1530. The Sydney is traveling along slowly on a parallel course some 1,000 to 1,200 meters distant. On her bridge one can distinctly make out the white tropical uniforms. The propeller of the embarked plane stops pin wheeling. They seem to consider us entirely harmless. A new signal is hoisted on the Sydney: “Whence from and whither away?” We answer, “From Batavia to Lorenzo Marques.”

Will our luck hold, and will they withdraw without recognizing us? Calmly I signal with my hat over yonder, although inwardly I do not feel too good, for eight murderous gun barrels are trained on us. I have the unpleasant feeling that they are all pointing at the bridge and that they have searched out my own stomach.

Seconds that seem endless go by. Now there is a new signal. What can it mean? “Give me your secret signal,” calls the signal man from the bridge of the Sydney. Now is the time for decision. The Captain quickly weighs the problem. If the right answer does not come back at once, they will be startled over there. “Well, Gosseln, there is nothing left to do,” he says to me.

Now in a matter of seconds the drama unfolds. The cue: “Down gun masks.” The German naval ensign is sent aloft to the gaff, while the Dutch flag is hauled down. Fore and aft there is a rattling of armored bulkheads coming up. Amidships the railing tilts over, and from the batches rise two cannon which are swung out with great dexterity by the gun crew and trained on the enemy. Simultaneously the cover disappears, and two ack ack guns rise up on their hydraulic hoists. Still there is no shot from the Sydney. They do not seem to have grasped the spectacle of the transformed merchant steamer.

A few seconds later, from our bridge, we break out a 4 cm. gun. On the bridge opposite we can see the shots hitting among the white uniforms. Almost at the same instant the first shot from our 15 cm. cannon falls 100 meters this side of the Sydney. A few seconds later go the first close salvos from the quad-mounts. A direct hit! The plane is burning. A gun aboard the Sydney is struck. Two torpedoes leave our tubes and splash in the water and seek their deadly course. Salvos two and three follow in four second intervals, each shot reaching the target.

But opposite us a turret gun has gone into action. The first shell whistles over us and splashes in the water to our leeward. They have completely forgotten to allow for the short range. Nevertheless, the gun captain opposite is a determined and courageous man. He continues to fire imperturbably despite the damage and ruin all about him. The Kormoran shudders as a shell hits her. Another shot whistles by the No. 2 gun above deck, and falls in the water to leeward without exploding. An announcement from the engine room: “Hit in the engine room.” An oil bunker is hit, and the burning oil gushes out over the engine room. A further announcement from below: “Obliged to abandon engine room.” A few seconds later there follows an explosion, and flames shoot up from the engine room skylight.

Our shells continue to explode on the Sydney without ceasing. Now there is a mighty explosion. A torpedo has hit just forward of the Sydney’s bridge. The Sydney is sinking with her bow in the water, and it looks as though she is going to the bottom. But now her bow rises from the sea, and she shakes off the mass of water. The brave gun captain has meanwhile fallen silent. Suddenly the Sydney changes course and bears down on us, striving to ram us with her remaining strength. We can only shoot and shoot, for our engines are now out of commission, and we can make only slight headway, without effective steering from the rudder. Will the last attempt by the assailant to destroy us fail?

Some hundred meters aft of our stern the Sydney changes to our port side. As the skipper and I go to the other side of the bridge, we notice that severe damage has been inflicted there. A shell has hit us in the smoke stack, and the shell fragments have wiped out the radio station and the lee bridge. Our navigator has been slightly wounded, and a boatswain navigator seriously wounded.

The Sydney is falling away from our port side, but our shells continue to explode. There is a loud shout on deck. Several torpedo tracks are said to be sighted coming toward us.

Slowly the distance between the ships widens, and the Captain orders: “Cease fire.” Aboard the Kormoran the fire spreads. The explosion in the engine room has taken severe toll of the personnel. Both our engineers have been killed. Only one man escaped from the command station at the last moment.

The burning ship has no way on. The firefighting equipment is destroyed, and the flames keep reaching farther and farther. With a heavy heart the Captain gives the order: “Abandon ship!” After all, who knows how long it will take for the fire to reach the munitions and the 300 mines we are carrying.

We are convinced that the Sydney had radioed at the beginning of the battle, and that by next morning at the latest warships from the Australian coast will pick us up. But what is the condition of our life-saving gear? Both motor personnel boats have been torn by the shell that hit us amidships, destroying our radio station. Of the other boats, only the one on the lee side is undamaged and seaworthy. The chief radio mate takes command of the boat’s crew. The boat is loaded up to the last place and shoves off from the side.

The wounded are gathered in our largest rubber boat, and some water and biscuit passed in. A second rubber boat is similarly filled, and both withdraw from the port side. On deck there is still a work boat, which has come from our tender, the Kulmerland. Originally it had a small screw which could be driven like a bicycle through a kind of step adjustment transmission. -Some days earlier the First Officer had had its transmission removed, and on the day after the holiday the carpenter was to cover up the hole in the stern. For the time being, the hole was covered with a patch. But how can we launch this heavy boat? Luckily, because of the artillery, the forward railing is collapsible. The boat is pushed to the side, and a jerk is enough to tip it over. In descending it bumps against the open torpedo valve, and then hits the water with a smack. By a miracle it does not capsize.

Special Leader B. is put in charge of the boat. Meantime I am sent aft to conduct rescue operations. Here are only small rafts affording space for one or two men. Some of the men standing about I send forward at once. The life boat on the after hatch cannot be launched, since it reaches across the entire hatchway, and can be hoisted only with a cargo boom.

After the one-man rafts have been distributed, there is only a small group of men left: Gunner’s mate M., his petty officer, and two of his mine crew. The attempt to throw the pig stall overboard fails, because of the resistance and the weight of its occupants. Quickly two empty casks are lashed to a couple of wooden beams to form a raft and launched. The mate and his two men get in. Amidships the fire is burning so intensely that any passage forward seems impossible. M. and I want to cross over to the raft which has been hauled up on the after deck. As we reach the spot, it has already been driven some meters from the stern. M. lowers himself over the side by a towline, and swims after the raft. (He never did reach it, but kept himself afloat during the night in a dog house. The following morning he was picked up by one of our lifeboats.)

I remove my shoes, then take off my jacket, folding it carefully, lay my cap in the middle of the pile, and lightly blow up my swimming jacket so that it will support me on one side but not hinder my swimming movements on the other. I climb down to the water.

Neither M. nor the raft is visible; hence I decide to swim in the direction taken by the lifeboats and the pneumatic boats. Aside from the Kormoran I can see scarcely anything. After awhile I encounter an empty cask. My attempt to hold fast to the barrel and rest a bit turns out disastrously, for the perverse thing begins to roll. I slip off and have to swallow a proper portion of sea water. Pfui Deubel! I slowly swim on. The choppy sea makes swimming difficult, and I have to protect myself by keeping my mouth closed. Gradually twilight wanes. As I am considering whether to swim back to the ship, I see some forty meters distant one of our lifeboats. This gives me new strength. Gathering myself for a final effort, I reach the boat.

To the question whether there is place for another seaman, a pair of hands reaches overboard. The first attempt to haul me in fails, for the rescuer pulls too hard on my white britches, and only the pants bottom lands securely, while I slip back into the sea. A second grasp, and this time it is a cinch. Completely exhausted, I sink to the bottom of the boat. The voices of my comrades seem to come from far away. After half an hour I come to and crawl toward the stern. It is the work boat in which I find myself.

Our “ship’s clown” comes along propelled on a sport mat. Like the passengers of the rafts, he finds admission to the overloaded leaking skiff. Not far away, Seaman B. is pushing himself on a raft. He does not succeed in reaching our ponderous boat. He goes out of sight, and we hear his shrill calls for help for some time. If he had only had the courage to abandon his raft and swim over to us!

We can see the Kormoran some thousand yards away. It seems to us that the fire has subsided a bit. One can still make out people up forward. I turn around toward the Sydney. Away in the distance one can see a fire on the water. From time to time there is a sudden glow, probably explosions of munitions. While we are pondering whether to remain in the vicinity of our ship on the possibility of going aboard next morning to stock up the boat with fresh water and food, there comes a terrific explosion. Flames and clouds of smoke rise to the sky, and even where we are we can hear the splashing of shell fragments on the water. Within a few seconds our proud Kormoran has disappeared under the waves.

We wonder whether the comrades we saw on deck half an hour ago have been saved. As we later find out in internment, the officers and some eighty men remained forward with practically no possibility of rescue. Forward in No. 1 hatch were two steel lifeboats. They were covered only by light hatch covers. All available tackle in the vicinity had been brought to action, and an attempt made to hoist the heavy boats on deck. At this point they had the benefit of the experience of our merchant marine officers Herr K. of Hapag and Herr D. of Lloyd. This feat of seamanship deserves a place in the annals of outstanding deeds of battle. Both boats were safely lowered into the water.

After one boat was occupied, it stood by while the second waited alongside for the Captain, who accepted the securing report from Adjutant Oberleutnant M. to the effect that the final explosion was assured. The Captain was the last man to leave his proud ship, which had been home to us for nearly a year. Hardly had the last boat with the Captain aboard pulled away fifty meters when the explosion broke loose. As though by a miracle, the boat and its crew remained intact through the shower of splinters. Dark night and silence reigned once more where a few hours earlier the thunder of gun battle had so suddenly disturbed the quiet of the Day of Atonement.

The battle itself had lasted perhaps twenty minutes to half an hour. By 2300 we had lost sight of the burning Sydney. Heavy torpedo damage and the many 15 cm. shells she had taken precluded her reaching the safety of the coast. Not one man of the brave crew was saved. Sailor’s luck and fate likewise took their toll of a hundred of our own comrades.

The 19th of November, 1941, is for us survivors a memorable day, not of joy, but of thanks to a fate that kindly spared us. Still more it is a warning to us for the future that we the living should join for peace as the waves of the ocean joined to cover the dead of the Sydney and the Kormoran in a common grave. Men beyond the seas can learn so that a third conflict shall not occur, and a Sydney and a German ship shall not oppose each other in murderous battle. If this can happen, then that tragic event makes sense, and I can close with the words written to me by a young Australian girl:

“The war is long over now, and we must all become very firm friends if we wish to place the world in a better state.”