The oath taken on commissioning or enlisting in the armed forces, begins, “I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States.” In constitutional law classes at our military service academies, cadets and midshipmen are taught that in honoring that oath they may be called upon to fight and die to protect a citizen’s First Amendment right to burn the flag, preach hate or damn U.S. warfighters.

Last week, in a less melodramatic vein, the Supreme Court ruled in United States v. Alvarez that service members also may fight and die to protect the First Amendment rights of frauds who falsely claim military decorations for heroism. The Stolen Valor Act criminalized the act of falsely claiming to hold the Medal of Honor, Distinguished Service Cross, Navy Cross, Air Force Cross and Purple Heart, among other awards. With sad regularity, we hear of imposters claiming outrageous feats in combat that resulted in high decorations. Quickly recognized as pathetic liars by those of us with military backgrounds, an unknowing public, eager to honor heroes, embraces the liars. The 2005 Stolen Valor Act finally gave authorities the means to convict and imprison imposters. Dozens of convictions followed. Athough sentences were usually no more community service, at least a federal criminal conviction resulted.

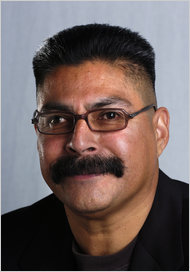

Xavier Alvarez was a particularly bold liar and fraud, claiming to be a retired Marine officer wounded multiple times and awarded the Medal of Honor. In fact, he never served a day in uniform. Across the nation, many others who wove heroic fantasies for themselves have been honored in a variety of ways, but it was Alvarez whose 2010 conviction came before the Supreme Court.

Arguments in the Alvarez case at the lower appellate level were typical. The prosecution held that the speech targeted by the Stolen Valor Act was within the well-defined and narrowly limited class of speech that historically has been unprotected by the First Amendment—obscene speech and defamation, for example. The lower appellate court found “Alvarez was not prosecuted for impersonating a military officer, or lying under oath, or making false statements to unlawfully obtain benefits. . . . He was prosecuted simply for saying something that was not true.” Historically, the court held, speech unprotected by the First Amendment has related to some criminal conduct or goal. The Stolen Valor Act, then, did not meet that standard, that court ruled.

Despite the Alvarez setback, and other similar outcomes, the Department of Justice appealed the Alvarez reversal to the Supreme Court. That court had jurisdiction because there was a diversity of opinions within the federal judicial circuits—some saying the act was unconstitutional, others disagreeing. But the government was in a legally weak position. Many will reluctantly agree that the failed prosecutions are the price of requiring our government to be very careful in attempting to decide what speech is and is not permissible. The prosecution of new Stolen Valor cases halted, waiting on the Supreme Court.

The fears of service members were realized in last week’s 6-3 Supreme Court opinion. Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote that, because the Stolen Valor Act imposes restrictions on speech content, it must satisfy the highest legal standard of constitutional review, a very high bar. Kennedy wrote that Alvarez’s lies were “a pathetic attempt to gain respect that eluded him.” But his lies were not illegal, Kennedy concluded.

Two other Justices wrote that a lower constitutional standard of review was applicable to the imposters’ claims but, even employing that lower standard, the law was still wanting. They held that, because the act applied even to family, social, or other private contexts where lies are unlikely to cause harm, the act created too significant a burden on protected speech.

Justices Samuel Alito, Antonin Scalia, and Clarence Thomas dissented. (Scalia’s son Matthew is a 1995 West Point graduate.) They held that lies about military medals merit no First Amendment protection whatever.

All of us tell an occasional lie, be it large or small. Absent an intent to achieve material gain or defraud a government agency by the dissembling, do we want the government to decide which prevarications are permitted and which can lead to criminal prosecutions? No one wants to see a contemptible liar who has never been in uniform get away with claiming an award for valor in battle. That demeans the award and is disrespectful to the service members who risked all to merit the award. In virtually all cases, however, the First Amendment bars government limitations on the content of our speech, even if that speech is grossly offensive. To service members, bogus claims like those of Alvarez are more than “offensive.” But, isn’t the protection of such untruthful claims the price truth pays to liberty? The Supreme Court says yes. Upon reflection, most will agree that the freedom to speak that the First Amendment shields must also protect those with whom we disagree. Indeed, it is those with whom we most disagree who most require the amendment’s protection.

Ultimately, when it comes to stolen valor, those who serve in uniform will grit their teeth and recall their oath to support and defend the Constitution.