The U.S. Air Force selected Northrop Grumman Corp. to develop and build the new Long-Range Strike Bomber (LRS-B) late last year. Like other recent big defense contracts, that award is under protest from competitors. But it’s a good bet the Air Force source selection was a sound one. Why? Because stealth matters.

As a submariner I fully appreciated the value of stealth—critical to the long-term undersea competition during the Cold War. To maintain a competitive advantage during that contest of low observability, the U.S. Navy ensured not only that each new class of submarines was quieter than the previous class, but also that each ship within the class was quieter than the ship before it.

The submarine I commanded in the late 1970s had an acoustic advantage over the potential adversary of 40dB—a 10,000-to-1 ratio of our sound to someone else’s noise. Practically, this could be expressed as being able to hear the adversary’s submarine 100 miles away while he could hear me only at a distance of a mile. That is the kind of unfair advantage one likes to bring to a military competition.

U.S. submarines have been made quieter during their lifetime, being stealthier when decommissioned than when they were brand new, but they eventually reach intrinsic technical limits for further refinement, making the next generation of platforms necessary.

During the platform’s lifetime, however, the special skills and techniques required to not only maintain stealth, but also to improve it, were developed through great effort. There is an analogy between stealthy submarines and stealthy aircraft here, as I understand that similar processes were developed and applied by Northrop Grumman to its B-2 Spirit bomber.

Six of the seven submarines I served on, including the one I commanded, were designed by General Dynamics Electric Boat. The one that wasn’t had to be significantly modified by Electric Boat during construction to substantially improve its safety and combat effectiveness. So there were some “unquantifiable intangibles” making this contractor the “go to” source for U.S. submarine designs.

Those intangibles have been made more real in the current partnership between Electric Boat and Huntington Ingalls Industries with their highly successful delivery of Virginia-class attack submarines (SSN-774) earlier than scheduled and below projected cost. It is also historically demonstrable that these unquantifiable intangibles tend to be volatile in nature, and atrophy if left unused. When U.S. shipyards other than Electric Boat became re-involved in nuclear submarine construction after a hiatus of many years, it took a considerable amount of help from Electric Boat for them to regain their expertise. This same story played out when the United Kingdom got back in the attack submarine construction game with their Astute class. There is no substitute for broad experience in designing, developing and maintaining all-aspect low observability when it comes to selecting the manufacturing source. In major acquisition programs such as a new submarine or new bomber, one wants to minimize invention and capitalize on innovation.

Moreover, even the best designed and precisely manufactured stealthy platform—well maintained and fitted with evolving technical improvements—will eventually need to be replaced by a newer design incorporating current technologies that cannot be “backfitted” to the older units.

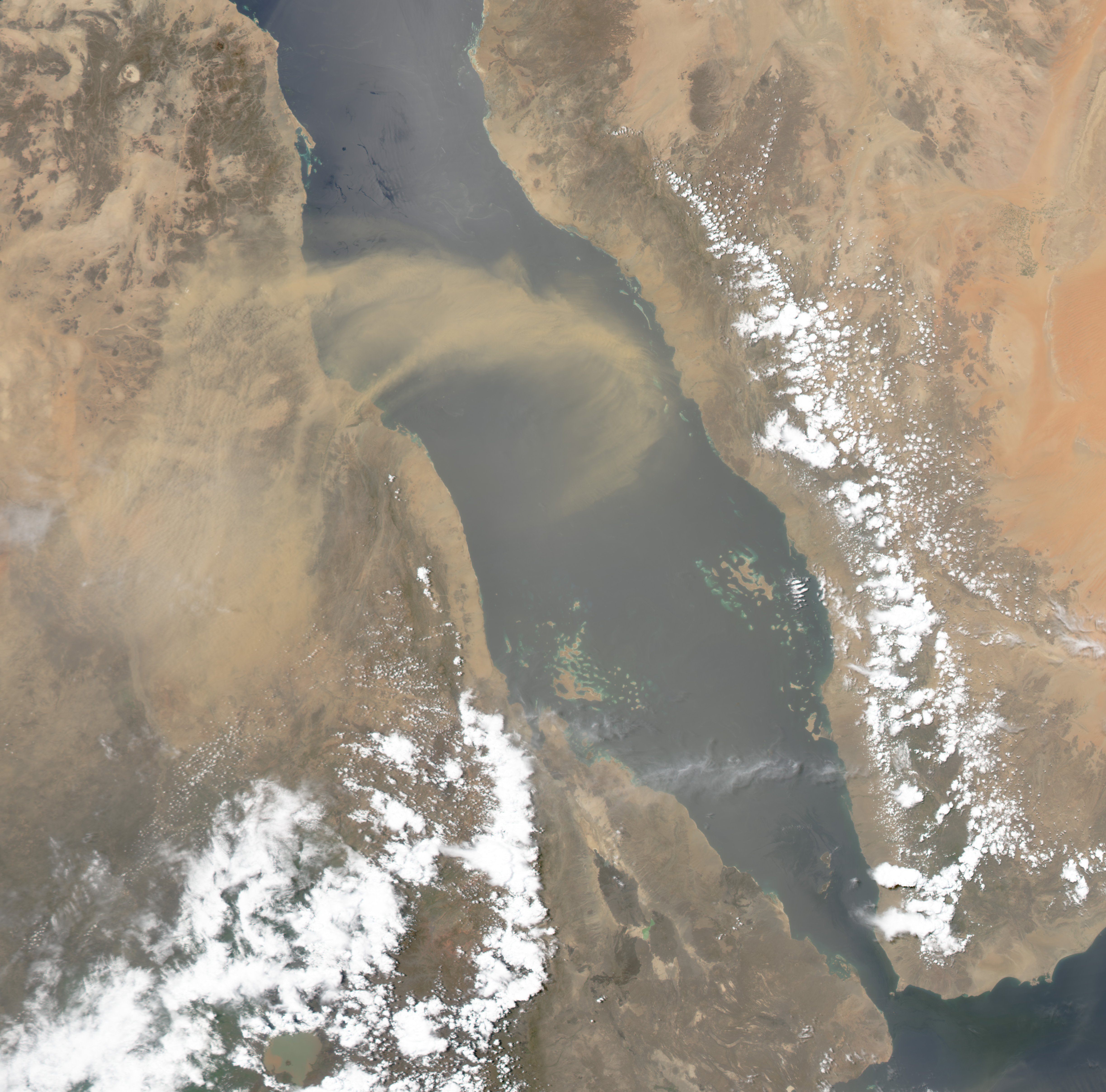

Although no then-existing anti-submarine warfare capabilities were effective against my ship when I was the skipper, a platform similar to it would be very much at risk in today’s environment. Again, an analogy with long-range combat aircraft is appropriate. Recently, Russia responded to Turkey shooting down a Russian aircraft (it allegedly violated Turkish airspace) by moving an S-400 surface-to-air missile system into Syria. Reports credit that system with the capability to engage aircraft out to 250 miles, and claim it is deadly against all NATO aircraft except the stealthy B-2 and F-22. Unfortunately, that can’t be said about the air-defense systems of a decade or two from now. Since the threat doesn’t remain constant, neither can the required capability to defeat it. That’s the task facing the builders of the LRS-B.

As a citizen I want the nation to have credible systems in its defense portfolio. As a taxpayer, I would like that portfolio to be funded in an affordable manner. As a former stealth warrior, I would like to hire the people who know how to design and maintain low-observable combat platforms. Stealth as a force multiplier has more than adequately proved itself both in the air and under the surface of the sea, and is an indispensable capability in carrying out critical missions against increasingly sophisticated threats. Every ounce of my experiential intuition as a stealth operator says that the best chance of obtaining a credible and affordable product is to have the manufacturers of the second class of stealth bombers be those who produced the first.