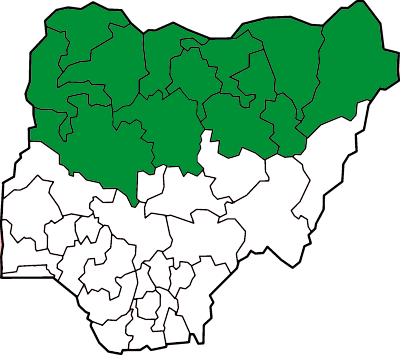

The fundamentalist militant group Boko Haram emerged in northern Nigeria around 2002 and since 2009 it has waged an unremitting, increasingly violent and increasingly sophisticated insurgency against the government of Nigeria, characterized by political assassinations, bombings, and attacks on Nigerian government institutions, Christians, apostate Muslims and government-run schools.

For nearly five years, the group has killed thousands across Nigeria’s north and yet none of its violent acts has succeeded in provoking the degree of revulsion worldwide as the 14 April kidnapping of 276 girls from Government Girls Secondary School in Chibok, in Nigeria’s northeastern Borno state.

The Chibok kidnappings now focus attention on numerous earlier attacks carried out by Boko Haram on government schools across Nigeria’s northeast, and also on an ideology which views Western-style education in Northern Nigeria as the source for the region’s host of woes.

Moreover, they provide a starting point for an examination of heretofore overlooked personalities, groups and events inside Nigeria which may contribute to our understanding of Boko Haram, its behavior, its sources of support, and its reasons for carrying out atrocities like that committed in Chibok.

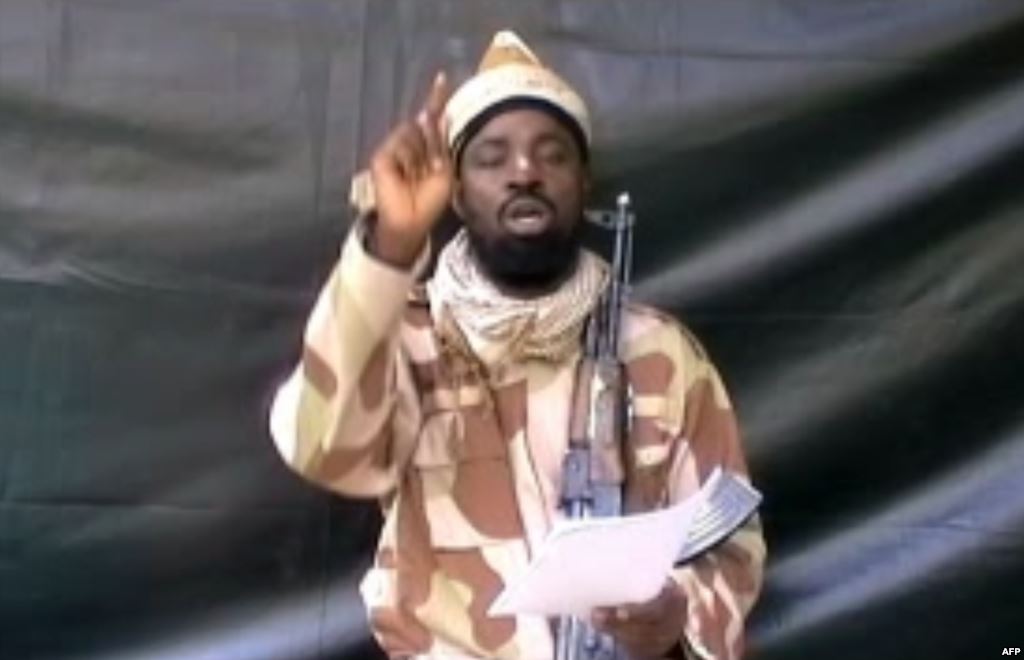

During a statement claiming responsibility for the kidnappings, Boko Haram leader Abubakar Shekau stated that “Western education should end.” In a separate statement issued 24 May 2010, Boko Haram said, “We will not allow adulterated conventional education (Boko) to replace Islamic teachings.”

Though the group’s formal name is Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati wal-Jihad, or “People Committed to the Propagation of the Prophet’s Teachings and Jihad,” its familiar name, Boko Haram—often interpreted as meaning “Western education is forbidden”—would seem to evince an ideological hatred of “non-Islamic literacy.”

Yet, the name means a great deal more. While haram, an Arabic loanword, refers to that which is forbidden in Islam, boko is a Hausa word which means “Something (an idea or object) that involves a fraud or any form of deception.” Western education is viewed by many northern Nigerians as “a fraudulent deception being imposed upon the [northern Muslim] population by a conquering European force “which undermines traditional Northern values.

The name Boko Haram might be considered shorthand for an ideology opposed to Westernization generally and to Western education in northern Nigeria, the conduit of Westernization, specifically.

Region of Skeptics

It is important to understand that Boko Haram itself did not construct this ideology opposing Westernization and Western education.

Not at all.

Rather, it is an ideology that for decades has been accepted by northern Nigerian academics, politicians, military officers, traditional rulers and university students to explain how, as they contend, the Western-style educational system was imposed on northern Nigeria by its British colonial masters.

They believe the system was, “not only decidedly secular but had taken a position against God and made materialism and hedonism the ultimate in life”—subverted the north’s traditional Islamic values, and replaced “morality, that sense of right and wrong which only consciousness of God confers,” with a kind of ruthless materialism.

Blame for the disparity between Nigeria’s impoverished Muslim north and the more-well-to-do largely-Christian south, as well as the rapacity of Nigeria’s leaders, is laid at the feet of Western education. As a proponent of these ideas asked, “If not from our educational institutions, where then is it [this decay and retrogression] coming from?”

Evidence of this mainstream northern Nigerian religio-political ideology, which opposes Western education, appears in 1996 in an edited work titled Western Education in Northern Nigeria.

The work, published by the National Gamji Memorial Club, a student association based at Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, includes chapters that present statistical information related to school performance, the education of women in northern Nigeria, and the education of nomadic peoples. Of particular interest, however, is a chapter authored by Usman Bugaje, a prominent northern leader, titled “Education, Values, Leadership and the Future of Nigeria.”

Bugaje lays out the problems of the North and their cause as he sees it: “Western imperialism, of which the educational system is the most potent weapon, has gradually and subtly eroded and supplanted the values and ideals of our pre-colonial societies . . . [and] initiated us into a virulent materialism which has since subverted our social morality, weakened our social fabric and crippled our socio-economic and political progress.”

The “only hope of escaping from this culture of corruption, decay, and mismanagement,” Bugaje tells fellow Northerners, “is by restoring our values and culture buried in the abandoned and forgotten history and culture of our pre-colonial societies . . . to dislodge the hegemony and monopoly of western liberalism and allow our own indigenous contributions to thoughts and ideas to compete favorably in our institutions of learning.”

With the aid of hindsight, that solution could be read as a fundamentalist’s call to jihad against Westernization and Western education in Northern Nigeria.

Northern Interest

Bugaje himself is interesting, not only for his provocative statements—for example, in March of this year Bugaje provoked the ire of Southern Nigerians when he claimed Nigeria’s Niger Delta oil resources were owned by the North—but for what he represents: a direct link that leads from this distinctive fundamentalist ideology to some of the most powerful Northern interest groups in Nigeria, including: the Northern Elders Forum (NEF) where he has been a member; the Coalition for Social Justice (CSJ) where he is chairman; the Arewa Consultative Forum (ACF) where he was formerly the secretary general; the militant group the Arewa People’s Congress (APC) where he is connected through his membership in the ACF and the Gamji Club; and others.

These groups members and patrons are a veritable who’s who of northern Nigeria’s political elite, including (circa 2002): former heads of state General Yakubu Gowon, Alhaji Shehu Shagari, Major General Muhammadu Buhari, General Ibrahim Babangida, and General Abdulsalami Abubakar, the Sultan of Sokoto Alhaji Muhammadu Maccido, and a host of others, all of whom, one might infer, are not only aware of Bugaje’s ideological attitudes but, by virtue of their endorsement of his authority within these groups, endorse his ideas as well.

This may be especially important when considered in light of the rise in Nigeria of ethno-religious paramilitary groups, like the Arewa People’s Congress, which coincided with the country’s return to civilian rule in 1999.

Ethno-religious interest groups, which have long existed in Nigeria, were largely suppressed during the decades of federal military rule (1966-1999). However, the return to civilian rule in 1999 brought forth from the shadows “a plethora of ethnic and regional organizations, some of them very militant, asserting rival group rights and pride” including three so-called “apex organizations” which represent the interests of Nigeria’s three largest ethnic groups.

These included the Afenifere, representing the interests of the Yoruba people of Nigeria’s southwest; the Ohanaeze Ndigbo, representing the interests of the Igbo people of the southeast; and the Arewa Consultative Forum (ACF), which represents the interests of the North.

Though banned by Nigeria’s federal government in 2000, each of these organizations quickly formed a paramilitary wing.

These ethnic militia groups, including the ACF’s militia wing, the Arewa People’s Congress (APC), “have been implicated in some of the worst cases of ethnic and religious violence . . . [to rock] Nigeria” since the nation’s return to civilian rule.

Following soon after a series of meetings with “Northern traditional rulers, retired judges and lawyers, retired senior members of the Armed Forces and the police, professionals, labor and students leaders [including members of the Gamji Club], market people, farmers and Politicians” which resulted in the establishment of the Arewa Consultative Forum, on 13 December 1999, two former army intelligence officers, Brigadier General Halilu Akilu — the Director of Military Intelligence during the Babangida regime accused of having carried out the 1986 assassination by mail bomb of Dele Giwa, the editor-in-chief of Newswatch — and Captain Sagir Mohammed, formed the Arewa People’s Congress in order to “carry out activities aimed at protecting and promoting the cultural, economic and political interests of the Northern states and their peoples.”

Though it now lurks in the shadows of Northern politics, the APC’s first impulses were accompanied by an abundance of provocative rhetoric.

“Should there be mayhem against our northern interests, the North will react by defending itself,” APC spokesman Asaph Zadok said.

Sagir Mohammed said, “We believe we have the capacity, the willpower to go to any part of Nigeria to protect our northern brothers in distress. . . . If it becomes necessary, if we have to use violence, we have to use it to save our people. If it means jihad, we will launch our jihad. . . . If they kill us fine. . . . You know that the Qur’an says the recompense is on the person who is committing evil, not any other person.”[i] Media reports suggest that, as a subordinate of the very well-funded ACF, which has collected hundreds of millions of naira [Nigeria’s currency] in donations from state governors and wealthy Northern citizens, the APC has the financial capacity to carry through on its threats.

In the APC, one finds a well-financed militant group intimately connected to the heart of northern Nigerian political power but also connected, albeit through Bugaje, to a fundamentalist ideology opposed to Westernization and Western education in northern Nigeria.

And in the APC one finds a militant group that, one might suspect, possesses in its leaders the military and intelligence expertise to carry out covert paramilitary operations, including bombings. And in the APC one finds also a militant group that, having those things stated, promulgates its intentions to launch into jihad.

The Boko Connection

While not intending to suggest here that the APC is Boko Haram, or that the group or its parent organization, the ACF, even support Boko Haram, those features of the APC that correspond to perceptions of Boko Haram appear as tantalizing avenues for research.

Some observers of Boko Haram may suffer from a form of apophenia. As Boko Haram’s tactics have evolved, from dane guns and machetes to car bombs and roadside improvised explosive devices (IEDs), they have interpreted this evolution as the result of cooperation between Boko Haram and al Qaeda or al Shabaab, though very little evidence exists to support such assertions. In the post-9/11 era, it is perhaps natural that such explanations are forwarded, especially when Boko Haram leader Abubakar Shekau has often spoken of the insurgency in terms of jihad and boasted of his relationship with al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb. Moreover, given the expansion of al Qaeda and its affiliates over the past several years, perhaps “it would be difficult not to see [evidence of a Boko Haram-al-Qaeda connection] in the signs littering Nigeria’s killing fields. Yet, these may indeed be “over-interpretations” of the phenomena that result in attributing rising violence in Nigeria to connections between Boko Haram and al Qaeda or other foreign groups in ways reality and the evidence really just do not warrant.

Boko Haram’s attacks on government-run schools in Nigeria’s northeast—including the 6 July 2013 attack on the Mamudo village secondary school in Yobe state, in which 42 students were killed; the 29 September 2013 attack on the College of Agriculture in Gubja, Yobe state, during which some 40 students were killed; the 25 February 2014 attack on the Federal Government College Buni Yadi, about 45 miles from the Yobe state capital, Damaturu, which resulted in the deaths of 29 teenage male students; and the latest attack in Chibok — should be viewed not as pointless violence perpetrated at the behest of an “unhinged” African rebel leader, as some analysts have suggested.

They should not even be viewed through the lens of global Islamic jihad, although jihad it surely is. Rather, they should be understood as part of an ongoing political-military campaign, a Northern Nigerian jihad, meant not only to rid northern Nigeria of its Western-style secular schools today, but to purge, conclusively, northern Nigeria’s Muslim society of the source of its “culture of corruption, decay and mismanagement.”

Yet, just as the “unhinged” African rebel leader explanation falls short of explaining the reasons underlying some of Boko Haram’s most loathsome acts, so, too, does the “al Qaeda” interpretation fail to provide an understanding of Boko Haram, its behavior, its sources of support, and its reasons for carrying out atrocities such as that committed in Chibok in ways that fall in line with Nigeria’s often-violent history and extremely complex political culture.

In the wake of the Chibok kidnappings, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry has vowed that the United States will, “do everything possible to counter the menace of Boko Haram.”

That effort should begin with a close examination of the overlooked personalities, groups and events inside Nigeria.