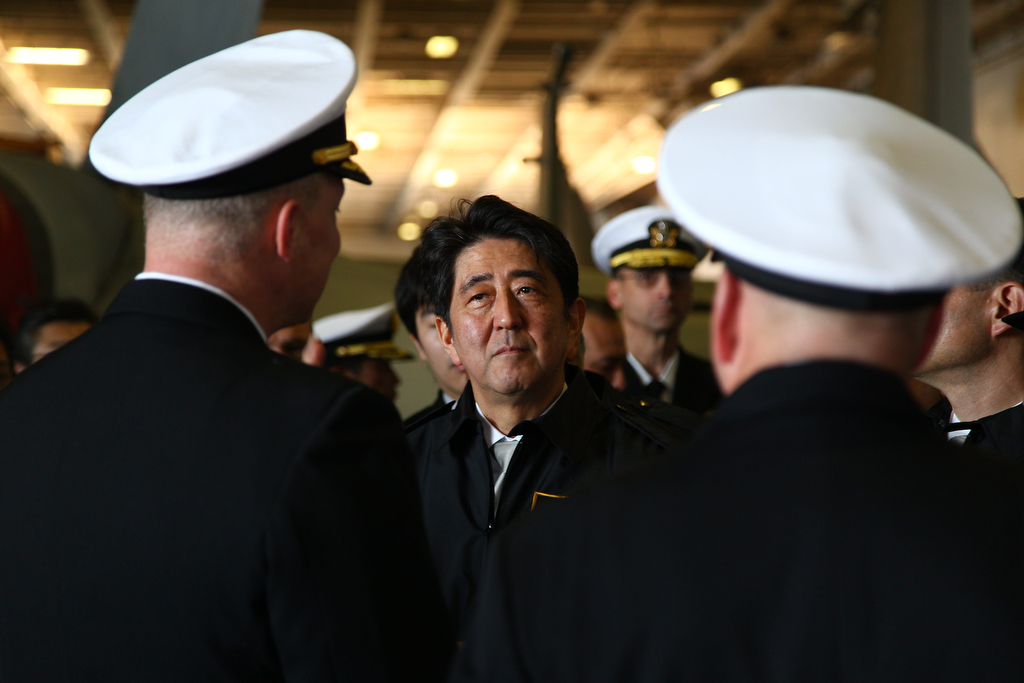

Former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who led Japan into a more active role in regional and global security over his eight years in power, was assassinated Friday at a campaign event in the western city of Nara near Kyoto. He was 67.

Abe, who served the longest consecutive term as prime minister in modern Japanese history from 2012 to 2020, left office citing health concerns but remained an important figure in Japanese political affairs and on the world stage. He is credited with shifting Tokyo’s focus from home-island defense and modernizing its self-defense forces to meet 21st-century challenges.

Although he came into office with an idea of improving relations with China and was the first post-World War II Japanese prime minister to visit Beijing, Abe was denounced by Chinese officials for his 2021 remarks over the consequences of an invasion of Taiwan.

Reflecting on his successor’s more assertive policy over Taiwan’s future and a changed constitution, Abe said “a Taiwan emergency is a Japanese emergency, and therefore an emergency for the Japan-U.S. alliance. People in Beijing, President Xi Jinping in particular, should never have a misunderstanding in recognizing this.”

Tensions between the Japan and China, especially over Beijing’s territorial claims on the Senkaku Islands, have steadily risen over the past decade from Abe’s time in office with increasingly frequent Chinese air and naval exercises, sometimes with Russian forces.

Starting under Abe’s administration, Japan recognized an “increasingly severe” security environment in 2014, in a Ministry of Defense white paper, as China built artificial islands to bolster territorial claims in the Pacific, North Korea aggressively tested missiles and nuclear weapons and Russia annexed Crimea, a Ukrainian province.

The paper called for a “dynamic defense” to address these challenges. Successive white papers have stressed jointness, interoperability with American and allied forces and securing new domains like cyber and space.

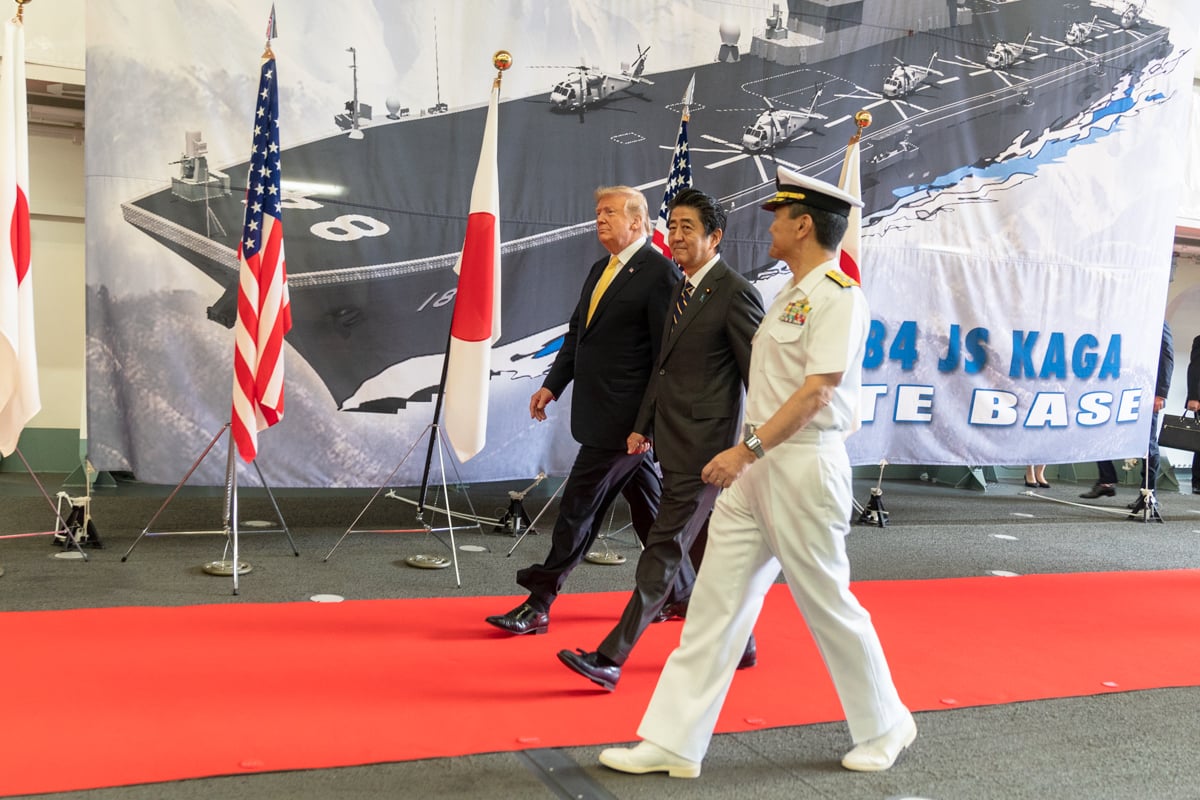

As Abe was leaving office, Tokyo took major steps to modernize the self-defense forces, such as agreeing to buy more sophisticated F-35A and F-35B Lightning II Joint Strike Fighters, revamp its naval helicopter carriers to handle the Short Take-Off version and produce more diesel-electric submarines.

The modernization program is continuing with Tokyo’s Fiscal Year 2022 defense budget of more than $47 billion. USNI News reported naval-related funding under the 2022 budget calls for the construction of five surface ships and a submarine. The budget includes 110 billion yen ($957 million) for the ninth and 10th ship of the Mogami-class frigates, 73.6 billion yen ( $641 million) for a sixth Taigei-class submarine, 13.4 billion yen ($116.7 million) for a fifth Awaji-class minesweeper, 27.9 billion yen ($242.9 million) for an oceanographic research ship and 19.6 billion yen (U.S 170.7 million) for a fourth Hibiki-class ocean surveillance ship.

In the Indo-Pacific, Abe was a key figure in developing the informal security arrangement known as the Quad among Japan, the United States, Australia and India. An example of that evolving relationship, as a counter to an increasingly bullying China over Taiwan, the Senkakus and in the South China Sea, came in 2020 when Canberra agreed to participate with the other three in an expanded Malabar maritime exercise off the Indian coast.

The military agreement bolstered Abe’s push for a major regional trade and economic development arrangement in the Indo-Pacific after the Trump administration backed out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership pact. He viewed the development alliance as an alternative to Beijing’s Belt and Road initiative in building key infrastructure from ports to airfields to highways in developing nations starting in Southeast Asia.

During Abe’s term in office, North Korea’s continued expansion of its nuclear arsenal and rapid development of missile technologies posed new threats in northeast Asia and across the wider Pacific to include Guam, an American territory, as well as Hawaii and possibly the U.S. mainland.

But relations with Seoul, another American ally, reached a diplomatic low point and, for a time, disrupted trilateral vital intelligence sharing among American, South Korea and Japanese militaries. The split was fueled by trade disputes and the tempestuous colonial history between Korea and Japan.

Intelligence on Pyongyang’s missile program was central to the partnership.

Integration of the three nations’ missile defenses remains a challenge and will be tested during this year’s RIMPAC exercise.

Relations were not always smooth between Washington and Tokyo during the Trump years.

With more than 50,000 American service members in Japan, how much Tokyo should pay for their presence, as well as U.S. military assets there, became a flashpoint that only ebbed when the Biden administration took office.

While often controversial for his political ties and economic policies, Abe successfully amended Japan’s constitution to allow collective defense of other nations, training regional coast guards and establishment of overseas bases.

As Abe was leaving office. Michael Green, now a senior adviser at the Center for Strategic and International studies, said at a panel session on the prime minister’s tenure he should be ranked “as one of, if not the most consequential prime minister” in Japan’s post-war history. “He intended to compete” economically and diplomatically and maintain Indo-Pacific security, Green added.