The small, rigid-hulled inflatable boat sped from the Brazilian Navy Frigate BNS Independencia (F-44) last week, taking an armed boarding team to a ship suspected of harboring illicit or piracy activities off western Africa’s coast.

It was just a practice drill, though, for the visit-board-search-seize team that climbed onto expeditionary sea base USS Hershel “Woody” Williams (ESB-4), which is serving as the training platform for exercise Operation Guinex that’s underway in the Gulf of Guinea. The area, with significant seaports and commercial traffic, is a known hotspot for piracy and theft on vessels at sea.

The exercise, which continues into September, is focused on U.S. and Brazil’s shared interest in maritime safety and freedom of commerce across the southern Atlantic, according to U.S. Naval Forces Africa. The VBSS operation was just one of several maritime training missions scheduled for Operation Guinex, the first U.S.-Brazil joint training to be held off Africa’s Atlantic coast.

“This is an important exercise for both of our navies,” Navy Capt. Chad Graham, who commands Williams, said in an April 25 NAVAF statement. “It was a pleasure working with the Brazilians and having their personnel embarked with us, and we look forward to future opportunities to cooperate.”

As Operation Guinex is showing, Williams‘ presence off western Africa, by design, gives U.S. commanders space to engage significantly with allies and partners on a military-to-military level in a place where the United States has no permanent, land-based footprint. The ship’s presence has increased the U.S. military’s interaction with the region’s navies and coastal patrol forces.

While U.S. forces have a footprint in East Africa at Camp Lemonnier in Djibouti – the only permanent U.S. base in Africa and one that supports operations in the Horn of Africa – there’s a much lighter presence in the west. But military officials and analysts say instability, security concerns and economic threats that continue to roil West Africa present opportunities for the U.S. military to strengthen partnerships and help the region’s countries to strengthen their military capabilities.

At more than 106,000 tons, the 784-foot-long Williams is among the largest U.S. warships this year plying the waters off Africa’s western coast. It’s a key region with routes for commercial ships carrying cargoes of food, supplies and fuel – including one-third of the world’s oil supplies.

For just over a year, after leaving Norfolk, Va., in late July 2020, Williams has been deployed to the U.S. 6th Fleet region to support missions in Europe and Africa. While officially homeported in Souda Bay, Greece, the mobile sea base has spent little time there over the past year because its permanent assignment is to U.S. Africa Command. Williams is the first Navy warship to do a dedicated mission to the region.

Williams, along with USS Lewis B. Puller (ESB-3) and USS Miguel Keith (ESB-5), is one of the Navy’s three ESBs that provide a large staging base for U.S. military forces doing a wide range of military missions, to include special operations and airborne mine countermeasures. Its flight deck covers more than one acre and accommodates four aircraft. Its hangar deck is large enough to support maintenance and its large interior spaces provide room for training and mission planning for any embarked units to include boats, rotary-wing and unmanned system operations, as well as the ship’s crew of 100 sailors and 44 civilian mariners.

The floating sea base is a platform not just for U.S. troops.

The operational impact of Williams is important, said Pamela Faber, a research scientist with Arlington, Va.-based CNA, a nonprofit research and analysis organization.

“The U.S. has certain strategic objectives in the Gulf of Guinea, and the Woody contributes to furthering those: Decreasing ungoverned maritime space; supporting regional stability; and strengthening the relationship both with regional partners and between the partners themselves,” Faber told USNI News.

The “real value” of the ship’s deployment, she added, is “in signaling the importance of how the U.S. is prioritizing the region, prioritizing the relationship with Gulf of Guinea partner-nations, the focus on relationship-building, providing an opportunity to train together, to build on the trust that the U.S. is focused on building in that region … and drawing attention to the issues.”

“The value of having it there,” she said, “shouldn’t be understated.”

Williams‘ deployment also brings the capabilities of a warship without having to draw from the Navy’s fleet of higher-end ships in demand elsewhere.

“This is an interesting case study in how the Navy can continue to support lower-end and lower-scale threats and missions in perhaps less-priority regions in an era of great power competition without pulling back entirely,” said Joshua Tallis, a research scientist with CNA and author of The War for Muddy Waters: Pirates, Terrorists, Traffickers, and Maritime Insecurity. “A lot of the debate about great power competition has been about how the Navy can deploy and employ relatively limited numbers of high-end assets in order to compete globally.”

“What the Navy has demonstrated here is that creative use of other types of vessel-classes offer the capacity to continue to engage with important allies and partners in important regions,” Tallis said, “without necessarily tying down your destroyers, cruisers and big-deck amphibs doing work that could, in theory, be done by different, and frankly, less capable vessel-classes.”

U.S.-Africa Interests

Africa’s population is estimated to reach 2 billion in 2050, representing more than one-quarter of the world’s people. But two-thirds today live in poverty, and drought, loss of arable land and economic stresses spur human migration that “feeds a lucrative market for extremist organizations and criminal networks,” Army Gen. Stephen Townsend, the AFRICOM commander, told Congress in April.

“Climate change, food shortages, poverty, ungoverned spaces, historic grievances and other factors make the continent also home to 14 of the world’s 20 most fragile countries,” Townsend testified. “Violent extremist organizations, competitor activities and fragile states are among some of the threats to U.S. interests.”

Africa “is important to the United States politically, economically and militarily,” he said, noting its role in international commerce and trade and watch over critical sea lines of communication. “Our future security, prosperity and ability to project power globally rest on free, open and secure access in and around Africa. Activities of competitor states, violent extremist organizations, instability and fragility all challenge our access.”

This especially includes access on land. “Much of West Africa governance remains weak and populations disenfranchised,” Townsend told the House Armed Services Committee. Violent extremist organizations “remain a significant threat and their violence continues to grow and spread.”

For the U.S., however, “access and influence stem from helping our partners with the problems they face,” he said. AFRICOM’s campaign plan for Africa has four objectives: Gain and maintain strategic access and Influence; disrupt violent extremist organizations threats to U.S. interests; respond to crises to protect U.S. interests; and coordinate action with allies and partners to achieve shared security objectives.

AFRICOM “resources offer cheap insurance and an ounce of prevention for America,” he told the Senate Armed Services Committee.

Training Together

AFRICOM in 2007 established the Africa Partnership Station, which is NAVAF’s flagship maritime security cooperation program, with goals to: develop maritime domain awareness to maintain a clear picture of the maritime environment; build maritime professionals; establish maritime infrastructure; and develop response capabilities while building regional integration.

“Building partner capacity is how we help the Africans and our international partners the most,” Townsend told the Senate committee.

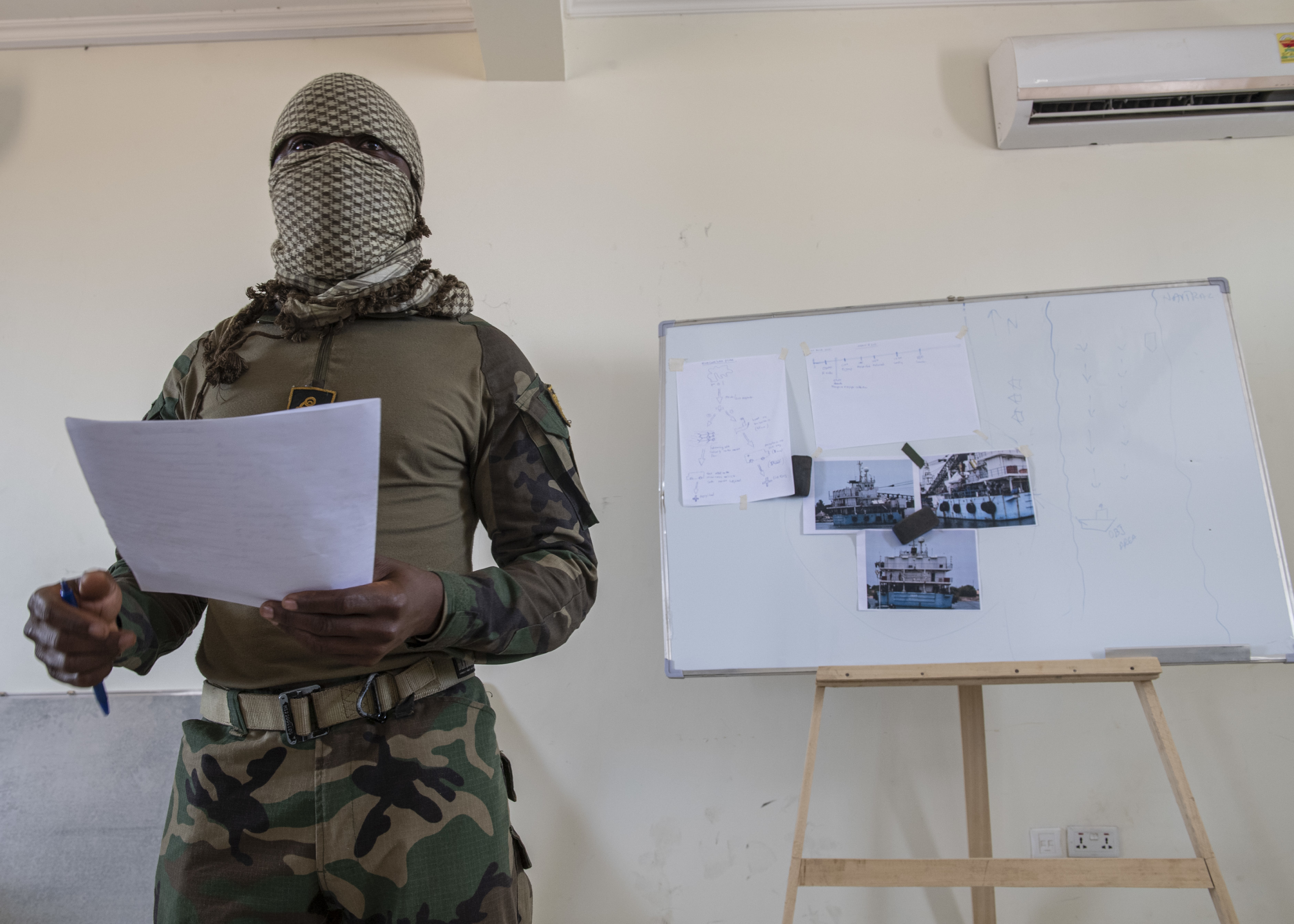

In early August, Williams joined the Nigerian Navy ships NNS Prosperity, NNS Nguru, NNS Ekulu, NNS Osun and NNS Ose in a maritime security capabilities exercise along with the Spanish Navy ship SPS Vigia and Ghana’s Special Boat Squadron, officials said in a Navy statement. The training exercise included maritime interdiction operations, shipboarding scenarios, fleet maneuvering, helicopter insertion and casualty evacuations.

That followed a short port visit to Tema, Ghana. “These maritime training operations required the collaboration of not one, but three countries’ navies, all working together simultaneously,” Graham, Williams‘ commander, said in a Navy release about the visit. “Collaborative operations like this offer invaluable experience for my crew in the present, but they also allow us to be more efficient and capable in future operations with our partners in the region.”

“The exercises we conducted this week show our commitment to the mutual goal of countering maritime crimes in the Gulf of Guinea, and how we can work together to achieve it,” he added.

Exercises such as Obangame Express, an anti-piracy and maritime domain exercise in West Africa, “is one way we seek to improve regional maritime domain awareness, capacity and cooperation,” Townsend told the Senate committee. “But this annual event is insufficient by itself. A multinational maritime task force is a good option to address the plague of piracy in the Gulf of Guinea. Additionally, piratical attacks in Gulf of Guinea have become more frequent and violent, causing risk to international commerce and threatening maritime security.”

Piracy Hotspot

In recent years, the Gulf of Guinea has been the global leader in piracy that’s becoming more violent than what was seen years earlier off Somalia and in southeast Asia.

Somali piracy was “a high-end, somewhat sophisticated operating model” while in southeast Asia “a lot of piracy was more hit-and-run style,” Tallis said. In the Gulf of Guinea, “we see the dominance of a new trend or a new model in piracy, which is the kidnap-and-ransom approach, where pirates will attack a vessel, take members of the crew off the vessel and back into strongholds on land and hold them for ransom there.”

“So it presents novel challenges both for U.S. allies and partners in the Gulf of Guinea,” he said, “and also for the U.S. in terms of trying to adapt to generate new types of capacity building to address that change in approach.”

“Most of the attacks are fast, smash-and-grab. Pirates don’t want to be aboard for a very long time because they’re at-risk in the open ocean. But it means that no one vessel is going to single-handedly resolve the regional piracy surge,” Tallis noted. But Williams‘ presence can “help regional partners to continue to refine their own response capabilities and expand their capacities to react at sea” with separate efforts on the land-based threat.

Those regional interactions also are helping them tackle other maritime issues. “Illegal fishing is a huge problem in the Gulf of Guinea,” Tallis said, and it’s seen as “more problematic and more devastating for local individuals if not the regional economy … than piracy or oil thefts.”

Faber said there’s “a growing awareness” among Gulf of Guinea nations “of the importance of the maritime space, for not only security reasons but also human security – fish being the primary protein source.” Fishing, cargo ships, oil tankers and oil exploration provide significant employment opportunities as well.

“But I think many countries in the Gulf of Guinea still prioritize land-based issues,” with resources given to armed forces and other organizations, she said, “sometimes for good reasons. There are very real, land-based security threats” they face internally.

A CNA evaluation of maritime security (MARSEC) initiatives commissioned by the Defense Department – U.S. Maritime Security Cooperation in the Gulf of Guinea, 2007-2018, an unclassified paper publicly released in May 2021 – looked at regional security cooperation with Benin, Cameroon, Ghana, Nigeria and Senegal. Among its recommendations were continued support of regional exercises, professional education and training programs; increasing bilateral and multilateral training on maritime operations centers for African partners; and the continuation of maritime security cooperation “beyond materiel needs, supporting African partners in setting a regional vision for MARSEC,” the paper stated. “Significantly reducing MARSEC efforts would risk the U.S.’s partner-of-choice status and reverse progress on MARSEC in the region.”

Stronger alliances and partnerships, in line with the National Defense Strategy, can ensure the United States is the “preferred security partner in the region,” it added.

“Deploying the Woody and developing the relationship and signaling intent – signaling that this region matters and this problem set matters – and growing relationships … can be directly linked to furthering relationships that can impact competition in the region,” Faber said. “There’s a link there. It’s a unique and interesting way of engaging with partners in the region.”