Fatal, serious accidents involving tactical vehicles could be prevented if the Marine Corps implements stricter oversight, enforces standards and ensures drivers and others get more realistic training, according to the Government Accountability Office.

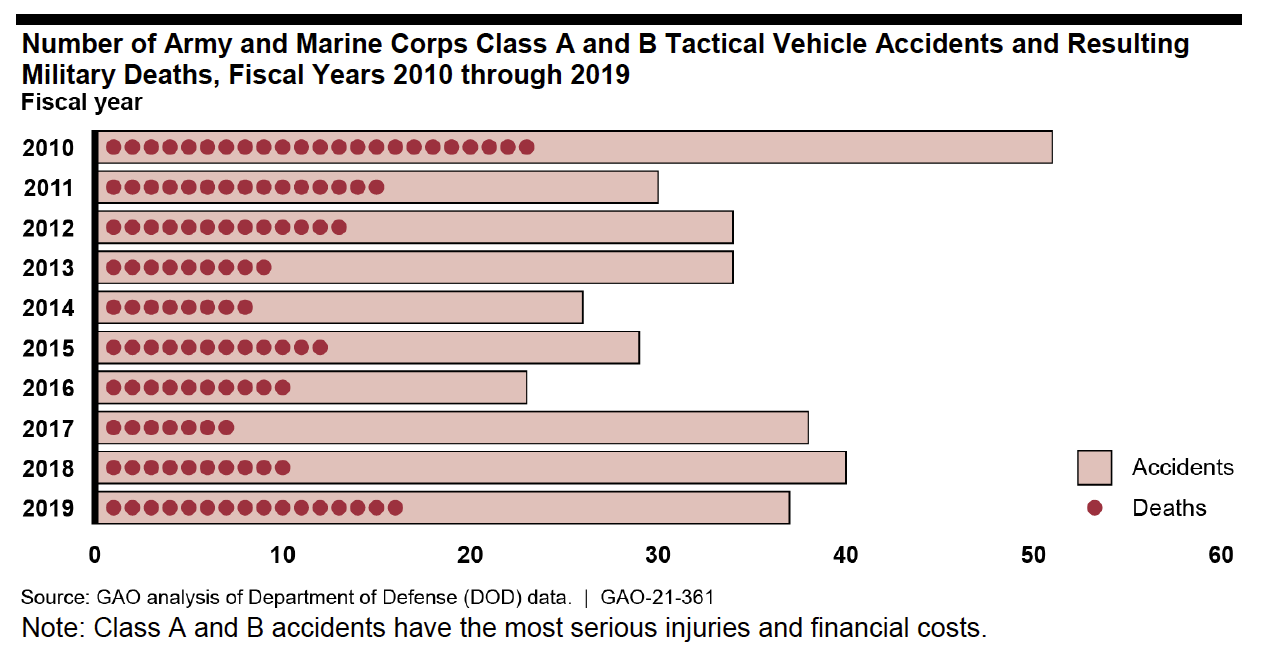

“Driver inattentiveness, lapses in supervision and lack of training were among the most common causes of” reported accidents from Fiscal Year 2010 to 2019 that killed 22 Marines and 101 soldiers, the GAO stated in a report released July 13. The report reviewed mishaps and Marine Corps and Army service-level actions. It found “gaps” in driver training, formal instruction, unit licensing and follow-on training.

While both services have safety practices in place, “units did not consistently implement these practices,” the agency concluded in its 103-page report. “The Army and the Marine Corps had not clearly defined the roles or put procedures and mechanisms into place for first-line supervisors, such as vehicle commanders, to effectively perform their role. As a result, implementation of risk management practices, such as following speed limits and using seat belts, was ad hoc among units.”

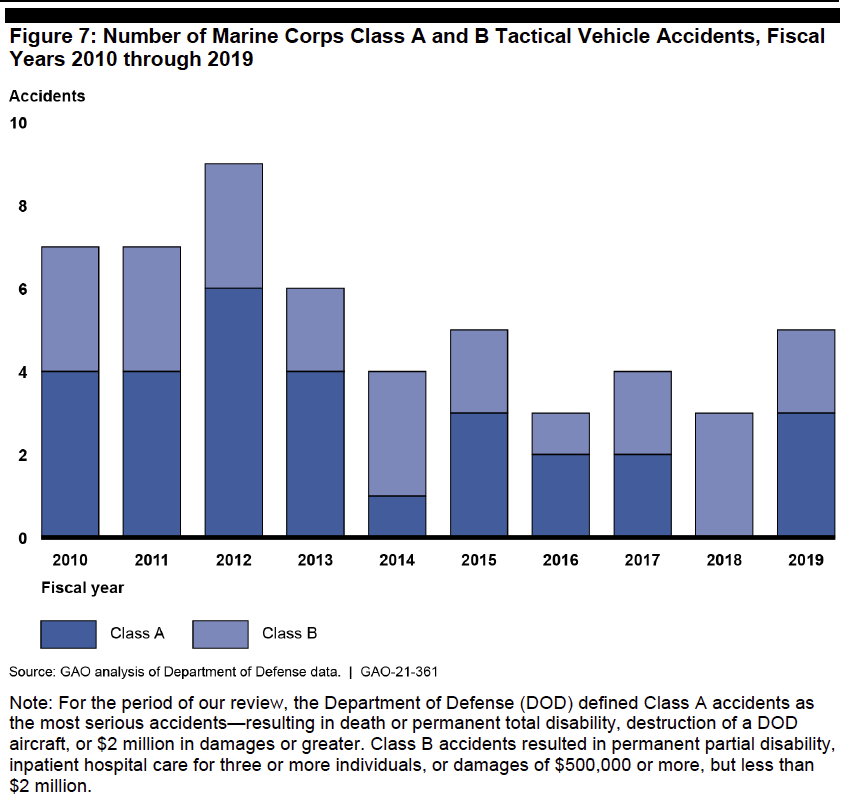

The Marine Corps recorded 662 tactical vehicle accidents – including 29 Class A mishaps with serious injury or death – during that period, while the Army had a total of 3,091, the GAO said. The agency found that vehicle “rollovers” happened in 24 percent of those mishaps and in 63 percent of any accident where a service member died.

The Marine Corps’ family of tactical vehicles includes the amphibious assault vehicle (AAV), the light amphibious vehicle (LAV), medium tactical vehicle replacement (MTVR), mine-resistant ambush protected (MRAP), high mobility multi-purpose wheeled vehicle (HMMWV) and military all-terrain vehicle (MRZR). The LAV had the highest mishap rate among these, with 4.3 accidents per 1,000 vehicles.

Recent fatal accidents include last year’s AAV sinking off southern California, killing a Navy corpsman and eight of the 15 Marines in the 26-ton vehicle returning to ship during the 15th Marine Expeditionary Unit redeployment training. In 2019, three Marines and 16 soldiers died in tactical vehicle training mishaps, including a Marine Raider in an MRZR rollover at Camp Pendleton, Calif., and a lieutenant when his LAV rolled over into a crevasse at the base.

The GAO report stems from a 2019 congressional request into non-combat deaths involving military vehicles following a rash of fatal accidents. “The results released today showed a troubling pattern of deaths and injuries despite the Army and Marine Corps having ‘established practices to mitigate and prevent tactical vehicle accidents,’” Rep. John Garamendi (D-Calif.), who chairs the House Armed Services readiness subcommittee, said in a July 14 news release.

“Right now, a cascading series of failures within the military is causing the U.S. to lose more service members in preventable training accidents than in combat,” Garamendi said. The report “highlights a troubling pattern of training shortfalls and supervision lapses that have led to a concerning rise in preventable training deaths throughout the military. My message to military leadership is clear: This will not be tolerated. The military must fully implement each of the recommendations that are outlined in this report to mitigate further, preventable loss of life.”

Michael H.C. McDowell, whose son, 1st Lt. H. Conor McDowell, 24, died in the LAV rollover, said he hopes follow-up congressional hearings will delve further into the report’s findings and include in-person testimony from victims’ families.

“The GAO report is a starting point. But its recommendations need to be strengthened, improved and added to. And the Pentagon must be ordered/mandated by Congress to implement safety reforms, which are quite cost-effective and will save lives and money,” McDowell told USNI News. Those safety reforms, he said, should include the use and availability of driver training simulators, and the Marine Corps must adequately fund and require that units use these simulators to supplement driver training and ensure safety procedures are known and followed.

“The Army and Marine Corps then need to report back to Congress and the public on what actions they have taken and when,” said McDowell, who’s been researching military vehicle rollovers and mishaps as a fellow in the international security program at New America, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit think tank. “These measures will absolutely save lives and spare families the cruel grief of the losses of their loved ones.”

But McDowell was less certain about the extent to which the Marine Corps would adopt those changes. “There has to be a leadership culture which accepts responsibility and is held accountable to Congress and the public,” he said. “I have no confidence that that is true.”

Human Factors and Managing Risk

GAO auditors reviewed safety data, mishap narratives and range documents and interviewed Marines in 11 battalions – three light armored reconnaissance battalions, two reconnaissance battalions, three infantry battalions, and three logistics and support battalions – along with soldiers in nine Army brigades.

“Human factors such as driver error, mindset, complacency and confidence were the most common causes of tactical vehicle accidents,” the GAO wrote, and “inadequate supervision and inadequate training or experience” were cited as causes more often than environmental or mechanical factors. “Driver error or rule violation” was cited in 83 percent of Marine Corps accidents.

The services’ safety initiatives include risk assessments, safe-driving practices, ground safety programs and spot checks, but “implementation of the practices differed among units,” the GAO found. These included “assessing risk, following speed limits, wearing protective restraints such as seat belts or harnesses, using ground guides to aid tactical vehicle driver situational awareness, and attending briefings prior to operating tactical vehicles.” At times, risk assessments weren’t done due to time pressure, low level of perceived risk or approval chain-of-command.

“Personnel we interviewed from seven of nine Army brigades and nine of 11 Marine Corps battalions cited complacency, overconfidence or inexperience as leading factors that affected a unit’s ability to consistently implement risk management practices,” the GAO wrote. Marines and soldiers said “the procedures and paperwork can become all-consuming, blunting the effectiveness of existing procedures and leading to an overall sense of complacency.”

Most of the units said “excessive speed” was “a key hazard and contributing factor to tactical vehicle accidents,” the report found. Seatbelt use was spotty, and Marines and soldiers reported restraints often aren’t used because they impede movement when tactical and protective gear is worn. Use of ground guides varied, the GAO said, and drivers in about half of the units “stated that they either did not participate in pre-mission briefings, the briefings were ineffective, or that the briefings were only conducted for field operations and not day-to-day operations.”

‘Ad Hoc’ Safety

The GAO found inconsistency in vehicle commanders’ roles to ensure safe driving practices, with some not properly licensed or formally trained on the vehicles they commanded. “Drivers in both the Army and Marine Corps described instances where it was up to the driver to inform the vehicle commander of their duties,” the agency found.

Moreover, “the Army and Marine Corps have not consistently established qualifications or put mechanisms and procedures in place service-wide, such as formal training, to help personnel effectively perform the role,” the report stated. “Without taking steps to more clearly define the first-line supervisor’s role in implementing safe driving practices and establishing mechanisms and procedures to help personnel effectively perform the responsibilities of the role—especially for vehicle commanders—the implementation of Army and Marine Corps risk management practices for tactical vehicle safety will remain ad hoc, which could increase the risk of accidents.”

Both services didn’t fully utilize safety officers, who would conduct spot checks on tactical vehicles, manage mishap reporting and promote safety awareness, the agency found.

An internal 2019 survey found that 45 percent of Marines didn’t know their unit had a safety officer, which typically is just one of several responsibilities assigned to them. Some units didn’t fill their safety billets.

According to the Marine Corps Safety Division, “safety positions are only staffed at 60 to 70 percent of what their staffing model recommends. This has presented challenges in performing the safety mission,” the report stated.

In fact, one senior officer told the GAO that “only one full-time safety professional has been staffed for an entire Marine Corps division, which consists of approximately 22,000 personnel, over 350 armored vehicles and over 2,300 tactical vehicles.”

Training Shortfalls

Driver experience varied by unit, the GAO found, and existing formal driver training programs and licensing requirements aren’t sufficient.

The LAV is the only Marine Corps tactical vehicle that has a separate, formal military school training. Drivers get six weeks of training and licensing at Light Armored Reconnaissance Training Company at Camp Pendleton. Marine motor transport operators train to a basic skill on the HMMWV and medium and heavy tactical trucks at Motor Transport Instruction Company at Fort Leonard Wood, Mo.

Drivers, though, often don’t get enough dedicated, follow-up training to build their skills and certifications once at their units, the GAO found, due to “lack of vehicle availability for training, lack of driving opportunities for less experienced drivers, and reliance on on-the-job training over driver-focused training.”

The Marine Corps’ Motor Transport Training and Readiness Manual, issued in June 2019, requires motor transport operators to show proficiency in specific tasks. It also details tasks that “incidentally” licensed drivers – those not with the motor-T operation occupational specialty – must do.

But neither the Marine Corps nor the Army “developed a well-defined process—to include performance criteria and measurable standards—to build and evaluate tactical vehicle driver skills from basic qualifications to proficiency in a diverse set of conditions (e.g., varied terrain or at night),” the GAO found. “Specifically, licensing programs in both the Army and Marine Corps do not have specific performance criteria and standards for training, and unit commanders lack deliberate progression models for training drivers in increasingly difficult scenarios.”

Licensing programs also were found to be inconsistent. While Marine divisions and logistics groups – all two-star-led commands – have minimum requirements for drivers, “officials told us that these are baseline requirements and that driver skill building – especially in diverse conditions such as varied terrain or at night – still occurs at the small-unit level.”

And that, too, varies, the GAO found.

“Drivers we spoke with stated that there were not enough opportunities for field training, and that more time was spent driving on paved roads, maintaining their motor pool operations, conducting vehicle maintenance and supporting other unit priorities,” the report stated. One unit considered having a dedicated week for drivers to immerse themselves in training to include nighttime rides, convoys and deep-water driving.

“Without a well-defined process for tactical vehicle driver training—to include unit-led licensing programs and unit follow-on training—unit commanders do not work from a consistent set of performance criteria and measurable standards to determine how much training to provide, under what conditions and how to evaluate performance,” the GAO found.

“In addition, opportunities for driver-focused training are not emphasized or prioritized by unit commanders and are limited in their ability to help drivers maintain proficiency in diverse conditions. Moreover, drivers of tactical vehicles will continue to have varied levels of experience, and military leadership may not know if personnel have the skills necessary to drive tactical vehicles under increasingly difficult scenarios.”

Hazards in the Field

The GAO met with training range and safety officials and found that the Marine Corps and Army generally fulfilled responsibilities managing their ranges and reporting to units any known hazards there. At least 25 percent of the serious accidents happened on training areas.

“We obtained maps that show rollover risk areas, low water crossings, historical accident locations and other hazards from several of the training ranges, all of which were informed by the reporting of hazards and accidents,” the report stated. “These tools convey hazardous conditions to units using the training ranges.”

But shortfalls remain. None of the three Marine Corps ranges visited – Camp Pendleton, Camp Lejeune, N.C., and Twentynine Palms, Calif., – track units’ locations, and only one has both tracked and wheeled vehicle driver training facilities. Those facilities could provide drivers in advance with realistic training to match the same conditions, such as steep hills and rocky gullies, they’d encounter in the field.

“Marine Corps officials we spoke with said that, ideally, they would like to be able to track the location of every Marine on the training range because it would help keep them out of harm’s way. It would also help the unit personnel responsible for overseeing the exercise by giving them an idea of people’s relative locations when they are unable to establish line-of-sight,” the GAO wrote.

Lack of funding often was to blame for the shortfalls. Defense Department officials “noted that resource limitations are an important consideration for implementing these methods to identify and communicate hazards to units. While investment in these methods can be costly, so too are accidents,” the agency wrote.

The GAO found some best practices used by some units could benefit others. For example, four of the nine training ranges required unit rehearsals before the training event. Familiarization training can help drivers navigate terrain that’s very different from their home base.

Recommendations

The DoD, Marine Corps and Army concurred with the GAO’s nine recommendations. One called for the Marine Corps, Army and both service secretaries to establish a formal collaboration forum “to share methods that are used to identify and communicate hazards at ranges and training areas,” the report stated. Doing so would better “share lessons learned and best practices related to ranges and training areas. This could lead to safer training operations and result in more innovations and efficiencies across training ranges.

“The Marine Corps has reviewed and concurred with the recommendations of the GAO report. In addition to improving our reporting culture and reporting mechanisms, the Marine Corps has a multi-front campaign to improve the operational capability of our tactical vehicle fleet,” said service spokesman Capt. Andrew Wood told USNI News. “From initial design and acquisition, to recruiting and training, and information sharing with our DoD partners, we are making every effort to reduce our mishap rate.”

Four recommendations stated that the Navy secretary, in consultation with the commandant of the Marine Corps, should:

- Ensure that the Marine Corps develop more clearly defined roles for vehicle commanders and establish mechanisms and procedures for tactical vehicle risk management to be used by first-line supervisors such as vehicle commanders.

- Evaluate the number of personnel within operational units who are responsible for tactical vehicle safety and determine if these units are appropriately staffed, or if any adjustments are needed to workloads or resource levels to implement operational unit ground-safety programs.

- Ensure that tactical vehicle training programs – to include licensing, unit and follow-on training – have a well-defined process with specific performance criteria and measurable standards to identify driver skills and experience under diverse conditions.”

- Ensure that the Marine Corps evaluates the extent to which its ranges and training areas are fulfilling responsibilities to identify and communicate hazards to units. If the responsibilities are not being carried out, the Marine Corps should determine if existing workarounds are adequate or if additional resources should be applied to fulfill these responsibilities.