The Marine Corps is about to revolutionize infantry training, more than doubling the length of initial training for enlisted infantry Marines and weighing consolidation of its core grunt specialties into a single, all-around infantry warfighter.

The transition – which aims to build Marines adept in ground weaponry that can tackle the higher-end threats they will face on the dispersed battlefields of the future – will focus as much on brains as brawn.

In a School of Infantry-West initiative, chess will be part of the pilot of a 14-week basic infantry training starting next month. The Infantry Marine Course, or IMC, will replace the eight-week Infantry Rifleman Course for new Marines assigned to the “03” occupational field. The new IMC course, as directed by Commandant Gen. David Berger, will grow to 18 weeks once enough instructors are assigned to the course. Infantry is the Marine Corps’ largest enlisted community.

“For entry-level training, this is a massive leap,” said Lt. Col. Walker Koury, who commands Infantry Training Battalion at SOI-West at Camp Pendleton, Calif.

The command, along with its counterpart at the School of Infantry-East at Camp Lejeune, N.C., runs the existing basic course where newly-pinned Marines initially assigned as basic infantry Marine (MOS 0300) receive one of several MOSs – rifleman (MOS 0311), machine gunner (0331), mortarman (0341) or infantry assault Marine (0351) – upon completion.

That’s about to change on Jan. 25, when the next class of basic infantry Marines arrive at SOI-West to start the new multi-disciplinary course.

The idea of including chess in training came when SOI-West’s IT Battalion officials took a deep dive into infantry training and how it should develop Marines who have a broad array of combat skills they’ll need in future battlefields likely spread out and far from higher-level commanders. The existing course, Koury said, creates “an automaton who has some finite skills that they can use in very specific environments, in specific times – so it’s not an all-around player.”

“Currently, we train a Marine that is automatic. What we are looking to do is deliver a Marine who is autonomous,” added Chief Warrant Officer 3 Amatangelo “AJ” Pasciuti, the IT Battalion gunner.

“We understand that this is a novel approach, that this is different than what the fleet is used to getting. This is different than what the Marines are used to seeing,” Pasciuti said, acknowledging the changes may meet some initial skepticism. But the Fleet Marine Force will get Marines “that are better trained, better prepared, better equipped – and they’ve been taught to think through this entire process.”

A Fundamental Shift in Training

For months, battalion leaders and course instructors pondered: What kind of infantry Marine should the training produce? They tasked an out-of-cycle training company to “come up with any idea that you have,” Koury said.

Just lengthening the existing course wouldn’t add significant value by itself. “We identified that just getting more training in the field is not the solution to the problem,” he said. Marines are trained to operate “in any place, anytime, but the kind of automaton, World War II type of training was insufficient. We also have to have the ability to think, as well.”

Students at the Infantry Officers Course “are incentivized to think. They are given problems, they are given tactical decision games…where the officer is presented a problem, a mission-type order, and then what he or she is required to do is look at our own techniques to be able to analyze a problem. Our enlisted is not trained that way,” Pasciuti said. But “in distributed operation, that may cost us time – time that we may need to make a valuable decision.”

Chess was among the conventional and unorthodox ideas tossed about to build that cognitive capability. Training isn’t just about telling Marines to “think more” but, rather, to engage them in ways where they can exercise their creativity with a warfighting mindset, Koury said, noting “this is just a different way for them to train their mind, which they’re pretty much not asked to do – up until this point.”

While a board game, chess is also a two-dimensional battlefield. Chess play is “a vehicle to allow the students permission to think,” Pasciuti said. “The object of chess here is to look at the battlefield in a number of different ways. So what we want the Marines to do – our end state – is to effectively understand where the Marine exists, where he or she can understand themselves in an environment with complex rules and within a complex scenario, where they understand their actions affect others, and how the enemy’s actions affect him or her.”

In those potential scenarios, he added, “they need to be able to understand the mission type order, and based off the commander’s intent and resources along, continue to execute their mission.”

With a modern, student-centric learning model, the course better reflects how today’s high-tech generation learns, schoolhouse officials say. Developing infantry Marines skilled in weaponry but also skilled cognitively will better position them for future operations, since Marines in the future might have to make decisions when gepgraphically apart from their higher commands or if the adversary disrupts communications. They might find themselves as the senior-most junior leader in a pickle, a “strategic corporal” concept dating 25 years to former commandant Gen. Charles Krulak.

If junior infantry Marines learn and train to make cognitive decisions as a private, Pasciuti added, “then the opportunity for them as a sergeant or a staff sergeant in the future will be massive.”

The new approach is rooted on the commandant’s broader vision outlined in recent articles and the Commandant’s Planning Guidance, Force Design 2030, and Learning, the Marine Corps Doctrinal Publication 7. “The effective message to the commandant is: We are listening. We hear you loud and clear,” Pasciuti said. “What we’re doing is we are taking a fundamental shift in our learning ideology of how we’re going to shape the Marine of the future, and chess is one of many revolutionary changes we are making within the infantry curriculum.”

Chess allows “the Marines to contextually understand where he or she exists in battlespace,” he said, and by introducing it early in the training, they learn to think and become conditioned to make decisions. “Whether or not the students understand the ideas of chess or the fundamentals of chess, we will teach them. We are not interested in teaching them rote memorization anymore. … We want free play. We want freedom of thought.”

Small-unit infantry leaders “are going to have to make decisions that are outside of their pay grade, and we want them to be comfortable in understanding that they can make those decisions,” he added. “Chess is that vehicle.”

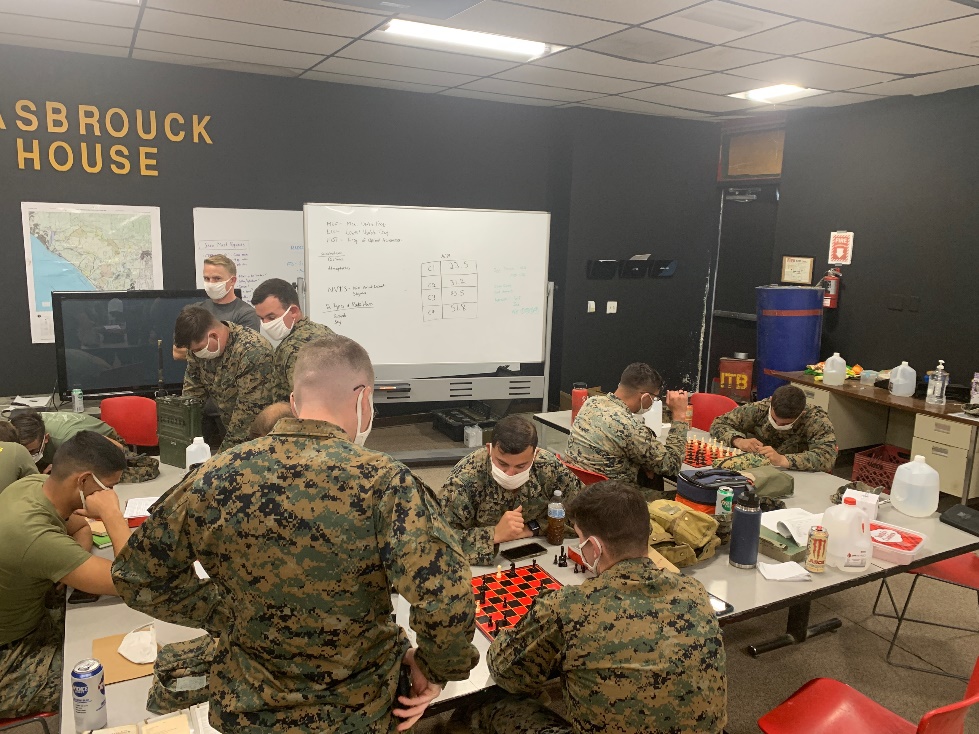

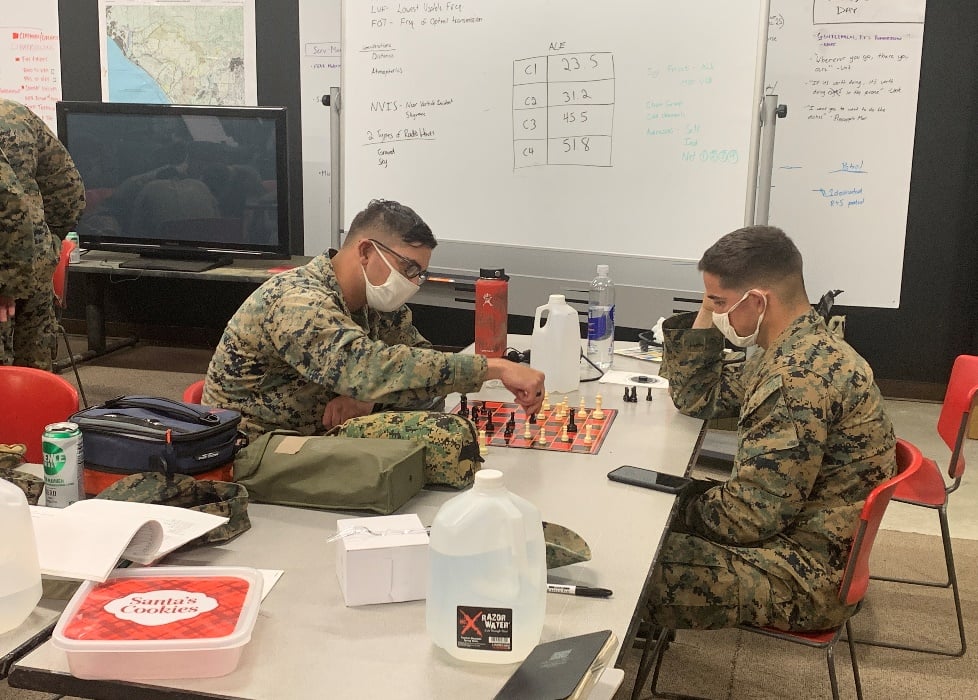

Chess Mates

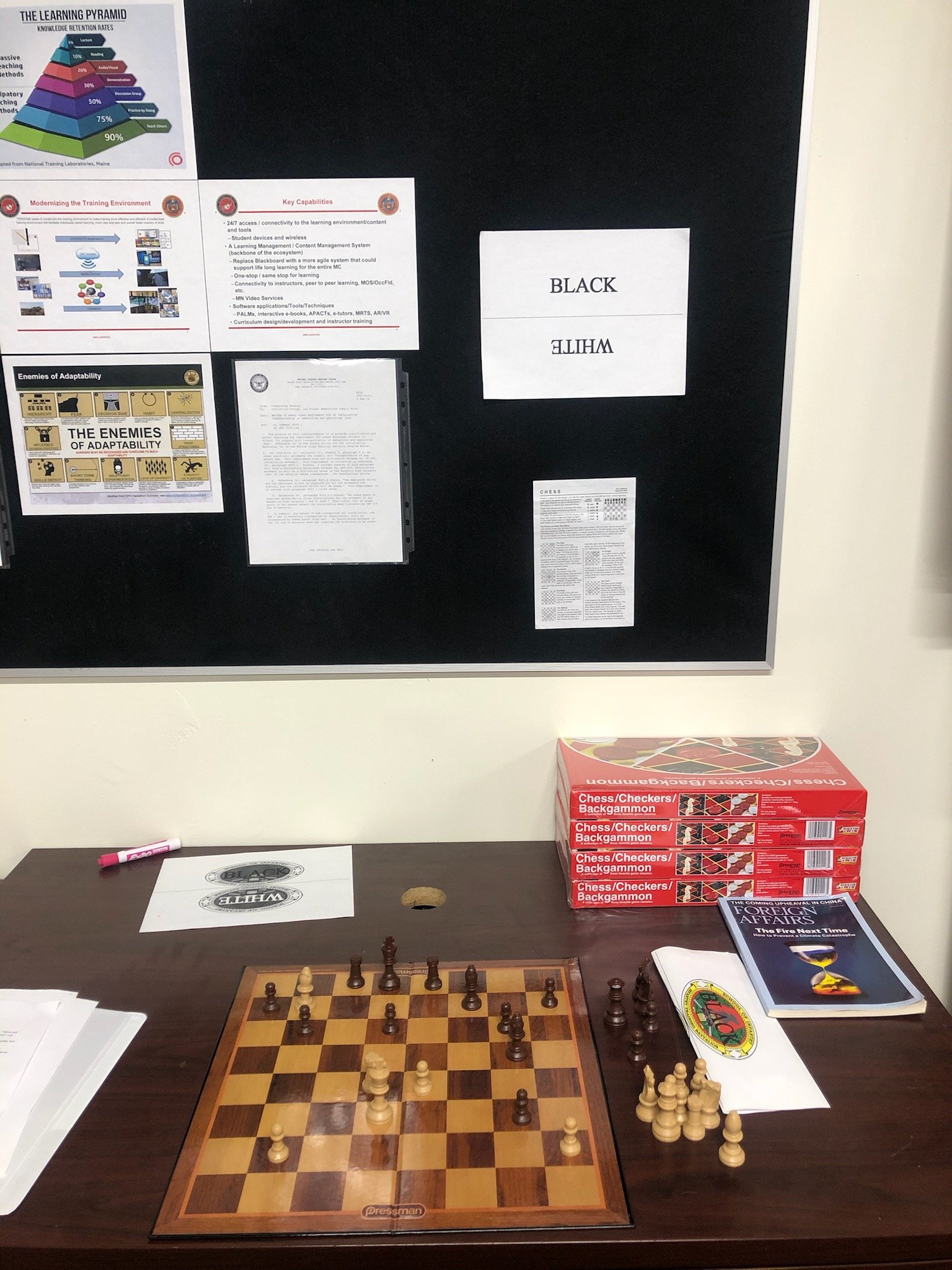

These days around IT Battalion at Camp Pendleton, there are chess boards in every office, and at any given time several boards are in play in the instructor ready room. Outside Pasciuti’s office is a chess board where instructors can challenge one another in continuous play, and sheets imprinted with “BLACK” and “WHITE” dictate the next move.

These days around IT Battalion at Camp Pendleton, there are chess boards in every office, and at any given time several boards are in play in the instructor ready room. Outside Pasciuti’s office is a chess board where instructors can challenge one another in continuous play, and sheets imprinted with “BLACK” and “WHITE” dictate the next move.

“Anybody can play this game at any time from any position. You walk by it and you recognize whether White is on top or Black is on top, and that is the next person to move,” he said. So a Marine who previously moved playing Black might an hour later have to play White, requiring a new strategy. “What this says is, you don’t get to execute your own plan,” he added. “You have to assess the battlefield as it is, identify strengths and weaknesses – and you sometimes have to abandon your own plan because now you’re working against what your initial onset was.”

Instructors will teach those unfamiliar with the game, and with incentives they hope to “make it cool, make it fun,” Pasciuti said. He wants students to challenge instructors “in not only a pull-up or a run competition but also a chess game.” By playing, he said, “it’s making smart Marines who can make decisions faster than their opponent or see deeper into five or six moves down the road.”

Among the ideas is Fire Team Chess. In one version, students one-by-one make their moves against another fireteam but under a time constraint. In another version, each fireteam member controls specific board pieces, “so now they have to be able to battle track one another,” Pasciuti said. And “they don’t have the opportunity to execute their own plan. They have to talk as a group” while under a time constraint, all while the “enemy” is there to hear and watch them.

“So it allows for nuanced communication, non-verbal cues, figuring out your own method to be able to move the piece when your enemy can sense what you’re doing and, in real time, react to it,” he said.

Pasciuti said instructors are looking at taking chess boards to the field so students, who are barred from bringing personal cellphones, “can talk about tactics, they can talk about shooting manipulations, patrolling formations. … So we’re exercising their mind as much as we’re exercising their bodies.”

Infantry and Chess

Success in chess, Koury said, comes with experience but also some luck. “You could only become better by exercising your mind,” he said. “So anyone is capable of beating anybody with their own skill.”

Pasciuti, for one, had to learn the rules. He hadn’t played the game, unlike some instructors in the battalion, and it was rough going initially. “It’s humbling. As the battalion gunner, I’m used to being the person who is the end-all, be-all with infantry,” he said, but he got routed several times by a sergeant.

Koury explained to him how chess pieces can represent tactical components more familiar to infantry Marines, like a combined-arms ground force: Rooks are direct-fire weapons. Bishops are like enfilade fire that can shoot at an angle. Knights are indirect fire weapons, since they can jump over other pieces and aren’t limited to specific boundaries. Pawns are the light infantry that can block, defend and envelop with supporting arms and, if used effectively, can become queens if they reach enemy territory. Queens are special operations, since they are few but move most freely. The king is your commander.

“I learned, very valuably, that I wanted to keep my indirect-fire assets as along as possible, even though they might be worth the same amount of points as something else,” Pasciuti said.

“My knight might be more valuable because with indirect fire I can attack the king, where maybe a bishop, through a direct-fire line of infantrymen, I may not be able to penetrate.”

All that might very well become more relevant in the new course as students train toward a single, multi-discipline infantry specialty, which according to a Marine Corps Training and Education Command spokesman is yet to be finalized.

In playing chess, a student has to decide which weapon will create the needed effect, Koury said. So instead of just focusing on a machine gun, for example, a newly-graduated infantry Marines will have to think about machine guns but also mortars, rifles, rockets and other weapons systems. “Chess allows them, since the pieces are all complex … to think about how my actions combine the effects of these pieces to achieve an overall effect.”

Koury also instituted small changes to the learning atmosphere and culture at infantry training. Students won’t be marched together around camp but will be expected to manage their time and figure out where to go on their own, and he’s told instructors to stop yelling at students. “We wanted to take away the restrictions we have on students and get rid of them and actually have them think on their own,” he said. “It came up as we are erasing, in almost its entirety, the whole program.”

“This could fail massively,” he added, but “we don’t just want to keep doing the same thing we’ve been doing.”

Still, noted Pasciuti, “there’s a general excitement around the School of Infantry. Instructors recognize they are at the forefront of this entire thing. They recognize that this is their course and that we are the advocates for them and we trust them wholly.”