The chief of naval operations remains mindful of deployment lengths, crew sizes, maintenance capacity and other measures of a healthy fleet even amid calls to grow the Navy to 500 ships or more, during what could be an important time in determining the future of the Navy.

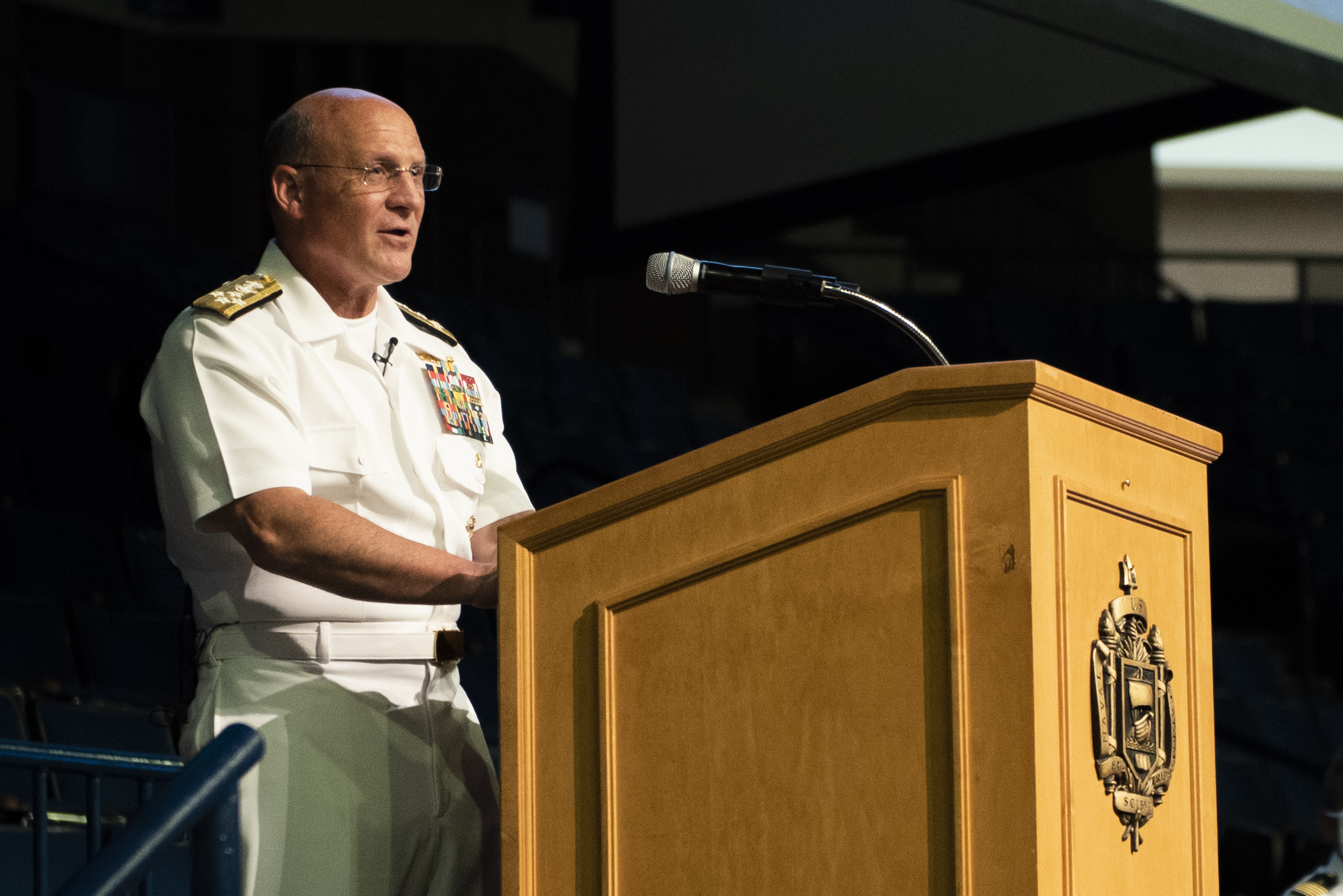

Adm. Mike Gilday said he’s not just preoccupied with what the future larger fleet will look like – though he has a good idea of what he wants from unmanned systems but is less sure about new manned concepts like a light carrier and a next-generation fighter jet – but also how to man and sustain the fleet, and how to operate it globally in a changing world.

“For me, what the right equation looks like going into the 2030s is a balance of readiness, lethality, and capacity,” he said in a Nov. 5 telephone interview with USNI News.

“The biggest unknown is the budget, right? And so if funding stalls – and obviously the [Pentagon’s Future Naval Force Study] is mere fantasy without the money to support it – then my priority will still be putting money against readiness and lethality. I’m not going to grow a hollow fleet. So as I’ve said publicly before, I need a more ready, more lethal, more capable fleet more than I need a larger fleet that’s less ready, less lethal, and less capable.”

Conscious of the cost and impact to today’s readiness, Gilday still expressed support for both a Navy and Marine Corps-led and a Pentagon-led future force review. The services’ Integrated Naval Force Structure Assessment looked at a 10-year window and what could be done over that timeframe to start fundamentally changing the fleet towards a focus on smaller and unmanned ships to operate in a more dispersed manner across the waters, whereas the Office of the Secretary of Defense-led Future Naval Force Study looked at how great a threat China could become over the next 25 years and asked how aggressively the Navy and Marine Corps could morph to meet that threat.

With “China being the most significant long-range strategic threat,” Gilday said, his focus is “changing the way that we’re going to fight with a fleet that’s affordable, right, that we can field in numbers. And if we’re going to operate in a distributed fleet among multiple axes to deliver lethal and nonlethal effects in every domain, those numbers do become important. But again, there’s the affordability piece.”

Though former Secretary of Defense Mark Esper had gone on a whirlwind tour to pitch the results of his study – which led to a Battle Force 2045 plan that he repeatedly touted since Oct. 6 but hasn’t been released in detail, pending White House review – with Esper’s firing this week by President Donald Trump, and little movement from elsewhere in the administration to approve and release Battle Force 2045, it’s unclear what the future of this future fleet proposal is.

Gilday acknowledged the merits of the OSD study but also had some reservations about parts of it.

Whereas Esper emphasized that the study called for somewhere between eight and 11 aircraft carriers – with potential reductions from today’s 11 helping pay for investments in new ships, including light carriers to supplement the nuclear-powered Nimitz- and Ford-class supercarriers – Gilday was firm in his call for 11.

“The FNFS validated the requirement for 11 aircraft carriers,” he said.

Additionally, he expressed reservations about the light carrier concept, saying that “I think we have to be very, very careful talking about light carriers right now and [putting] ourselves in a position where we’re going to make an investment in anything other than the Ford-class. And the reason I say that is because even in the assessment itself, [Esper] essentially said that there is a lot more rigorous analysis required of light carriers before we make any determinations of what those numbers might look like in the future. That’s why the range goes from zero to six.”

“Right now we’ve got the Ford-class in a really good place in terms of actually being ahead of schedule as compared to a year ago, where it needs to be to finish up its testing phase, to do its shock trials, to go into a maintenance availability, and let me get that carrier out there operating in 2022,” he continued.

“I don’t want to distract myself with yet another platform that – whose mission is yet to be defined, whose payload is yet to be defined. And again, I go back to [Littoral Combat Ship], Zumwalt [destroyers], et cetera. I want to focus on what I need to get right now, what I need to deliver – and less about these excursions, in a budget-constrained environment, that carry risk.”

USNI News has previously reported that the Navy’s original INFSA called for more carriers – between 10 and 12 – and did not call for light carriers, compared to Esper’s call for dropping to eight to 11 supercarriers and adding up to six light carriers.

Gilday acknowledged there are other areas of INFSA and Battle Force 2045 where he’s more comfortable moving out on now.

Topping the list of where he’s certain the Navy needs to invest is unmanned – but he stressed the need to do so carefully.

“Unmanned platforms – that’s the future, right? And so a hybrid fleet is where we’re going, make no mistake about it,” he said.

“We have a really good sense of what we need” from unmanned systems in the air, on the sea surface and under the water, he said of their requirements and missions. But all the same, “as I sit down and I think about what we’re going to need in order to field a fleet in a distributed fashion, I’m mindful of mistakes we’ve made in the past: whether it would be Littoral Combat Ship, whether it would be the Gerald Ford-class aircraft carrier, whether it be the Zumwalt-class, you know, Seawolf – I mean, you go down the line of projects that the Navy’s had that haven’t quite panned out the way we thought they were going to pan out. And so our approach needs to be deliberate, but there needs to be a sense of urgency as well. And there’s a balance there.”

He also noted the importance of the networks to support the unmanned systems, which must be delivered this decade, he said. To get after this development, the Navy recently launched Project Overmatch.

He said the Navy needed to move out on the Constellation-class frigate, which is in detail design now, and he said a future large combatant will be important too, if in smaller numbers than previous fleet designs called for.

“We can’t afford to wrap a couple of billion dollars’ worth of steel around 96 missile tubes,” Gilday said, explaining why large manned combatants would play a smaller role going forward.

But he explained that a “DDG-Next” ship would be important still.

“It’s smaller than Zumwalt, but it’s going to have the depth to be able to handle missile tubes that can support weapons with greater range and speed than we have today. So the Mark 41 launcher is tapped out with respect to capability,” Gilday said.

“We’re doing a lot of research on, and have had a lot of success with, hypersonics. And so that’s a way ahead. And to put a weapon with that kind of range and of that size on a ship, I’m out of the space to be able to do that on a Flight III DDG. And I have to move to a bigger ship, but it’s not going to be a behemoth. It’s going to be probably slightly bigger than a (Arleigh Burke-class) DDG, but smaller than a Zumwalt. And the idea would be we would use a new hull form, right, but the combat system would be a system that’s already fielded on our existing ships.”

Though the Navy needs to be cautious to avoid making mistakes, he said, there’s no time to waste in getting started developing and fielding these new kinds of ships and weapons.

“If I go back to the point I made earlier about China being the most strategic threat: I think that if we don’t get after it in a big kind of way this decade, if we don’t deliver FFG(X) like we need to, if we don’t deliver unmanned and we don’t deliver the network we need, if we don’t deliver for the warfighter, if we don’t deliver ready relevant learning and live-virtual-constructive like we need to, I believe that there is the risk that we’re going to fall behind and be in a position where we’re not going to be able to catch up.”

Gilday said much of the ability to do this rests on budgets.

He hopes that an additional $4 billion a year in the near term will be enough “to deliver more hulls, but also the manning, training, equipping, and all the other connective tissue that’s required to keep the fleet running.”

But, “where’s that money going to come from? Again, I go back to the comment that without money it’s mere fantasy.”

He pointed to an ongoing effort started by former Acting Secretary of the Navy Thomas Modly and continued by current SECNAV Kenneth Braithwaite to find at least $8 billion in savings a year for the next five years to pour into shipbuilding and related efforts to grow the fleet.

But Gilday made clear that that money cannot come from manpower, training, maintenance, operations or other accounts that would hurt readiness to buy a larger fleet. In fact, he’s trying to move the other direction, spending more money per ship to increase the size of the crew and schedule advanced training opportunities.

“Back when I was in command in the early 2000s, we did optimal manning and we cut manning significantly – ships like DDGs with 325 or 330 people went down to 250. Since 2017 – if I look between 2017 and 2020, we have bought back an additional 23,000 sailors. And so we recognize we made a mistake. And now we have been buying those billets back and funding them, and recruiting like crazy so that we can keep that pipeline going and get those sailors into the fleet, and basically cover down on those gaps that we know that exist and were kind of waved off as a way to save money and put against other stuff,” the CNO said.

Even the unmanned systems will require personnel, and he said the Navy is working through concepts of operations and employment to understand what personnel will be needed to operate and maintain them without taking away from other fleet activities or short-staffing ships that may be working alongside these unmanned craft.

“Time will tell on whether this plays out as we would like it to play out. The FNFS is still over at the White House, so it hasn’t been released yet. And then, of course, there are budgets to follow that would have to put the department’s money where its mouth is with respect to whether we need – whether they believe that the nation still needs a Navy of that size with that kind of capability.”