The Navy is kicking off a pilot program for an autonomy lab that would eventually help test and integrate new advances in autonomy software with existing unmanned vessels, keeping the unmanned fleet outfitted with the newest capabilities for the lowest development cost.

The Rapid Autonomy Integration Lab (RAIL) is beginning as a pilot this year and would become a formal effort in Fiscal Year 2022 if the Navy can secure the funding. Capt. Pete Small, the head of the Unmanned Maritime Systems Program Office, told USNI News RAIL is “the next logical step forward in executing the Navy’s vision for developing and deploying unmanned systems.”

After a couple years of laying the groundwork with common control systems and common combat systems, to ensure improvements benefit all unmanned surface vessels (USVs) and unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs), “the RAIL concept will build off of those efforts to provide infrastructure, tools and processes to develop, test, certify and deploy new and updated autonomous capabilities to those vehicles. It really addresses the fundamental question, how will the Navy quickly and effectively develop, update and maintain our autonomy software?”

Autonomy software helps unmanned vehicles understand the environment around them, navigate safely, and conduct their missions. As that software improves, or as the vehicles are asked to do more in more complex environments, the Navy wants to be able to update existing vehicles with new software packages rather than having to buy new vehicles. The vision is similar to Aegis Combat System updates for Navy surface combatants, where new capabilities can be added to the ships through software block upgrades.

Small described the pilot program that will run from this year to next year: his program office will take an in-service unmanned vessel – in this case, a Razorback UUV operating in UUV Squadron 1 (UUVRON-1) in Keyport, Wash. – and seek to integrate software code for a new autonomous behavior recently developed by a third-party vendor – in this case, the Office of Naval Research.

“This is really representative of what we want to do in the future: there’s a new capability, we want to put it on an existing vehicle.”

As part of the RAIL pilot, the program office will run the new software code through a series of cloud-based tools that use the Air Force’s Platform One software-development environment. These tools will check the software to make sure the code is all correct and perform vulnerability scans to ensure it meets cybersecurity and information assurance requirements. Integrators will then take the new code and the existing autonomy code written by the UUV vendor and stitch them together, Small explained.

The updated autonomy software package would then go through software-in-the-loop testing using modeling and simulation tools, then hardware-in-the-loop testing in the lab setting, and finally in-water demonstrations using the Razorback itself.

Small said the RAIL pilot program will focus on this one new autonomy behavior and the one UUV, but the ultimate vision for RAIL would be to support all UUVs and USVs throughout their entire lifecycle.

A vendor offering the Navy a brand new UUV or USV would be able to put its basic autonomy software – the package of behaviors that allows the vehicle to do basic operations – through the RAIL. But another vendor could also put an “a la carte behavior” through the lab, with the coding to give a specific unmanned system the autonomy to successfully conduct a certain warfighting mission in a certain kind of environment.

“It really is intended to serve all of those kinds of autonomy developers, but then there’s also a bunch of side benefits that we hope to take out of the RAIL, one of which that I mentioned already is cybersecurity: maintaining cyber accreditation will be a key functionality of the RAIL,” he said.

Small added that the Navy and Pentagon test and evaluation offices may also be able to leverage RAIL, since “we’re going to have to prove out these autonomy capabilities, and we certainly hope to do that with software in a modeling and simulation environment, and again progressing to hardware-in-the-loop testing as required, but also taking credit for that test and evaluation effort with more formal T&E oversight communities such that we can take credit for that rigorous testing that’s gone on in the RAIL in that development environment prior to putting the vehicle on the water and doing the more expensive and time-consuming vehicle-level testing.”

Though Small made clear that RAIL was mean to supplement, not replace, vehicle testing in the water, he said he hoped it would provide another set of data to make operators, engineers, lawmakers and others more confident that these USVs and UUVs were the right investments for the Navy to make to achieve its vision of distributed maritime operations.

“I think it will absolutely support our ability to gain credibility and confidence of a variety of stakeholders, including Congress, because it’s true, we need full-scale prototypes to go prove out the technology and learn and figure out how to employ them. But when we have those prototypes and we have this ability to rapidly upgrade their autonomy baselines, but also test it and run it in a modeling and simulation environment, we will be able to provide data that tends to add credence to concerns over reliability and just the technology of unmanned systems and military weaponized unmanned systems,” Small said.

“When we have the RAIL up and running, we’ll be able to provide thousands of hours of operations in simulation, plus the full-scale on-water demonstrations, to really build credibility for our plans in rapidly deploying and developing these things. So I think it will really quickly advance our ability to show progress, because right now we’re subject to getting the full-scale vehicles and running and operating them, and that just takes time and money to do. And we’re working on that, but the RAIL will certainly kick-start those efforts to provide more data to explain ourselves.”

The start of the RAIL pilot program comes after about three years of the Unmanned Maritime Systems Program Office working on common elements of the planned unmanned systems fleet: a common control system that would work for all the major surface, underwater and air systems the Navy will operate; and the Unmanned Maritime Autonomy Architecture (UMAA), a set of standardized architectures to organize software code and common interfaces to ensure they’re all interoperable.

Small said the RAIL wouldn’t be possible without Navy investment in the UMAA previously, since the architecture tells industry how to organize the code, allowing the RAIL tools to more easily know what they’re looking at for testing and security screening, and since it guarantees that the existing and the new code will stitch together properly due to their requirement to use the standard interfaces.

Additionally, the UMAA effort created “an interactive group of government, industry and academia that have regular engagement” on autonomy. Small said this group would be a key part of pushing out future requirements for new specific autonomy behaviors to develop and then test and integrate in the RAIL.

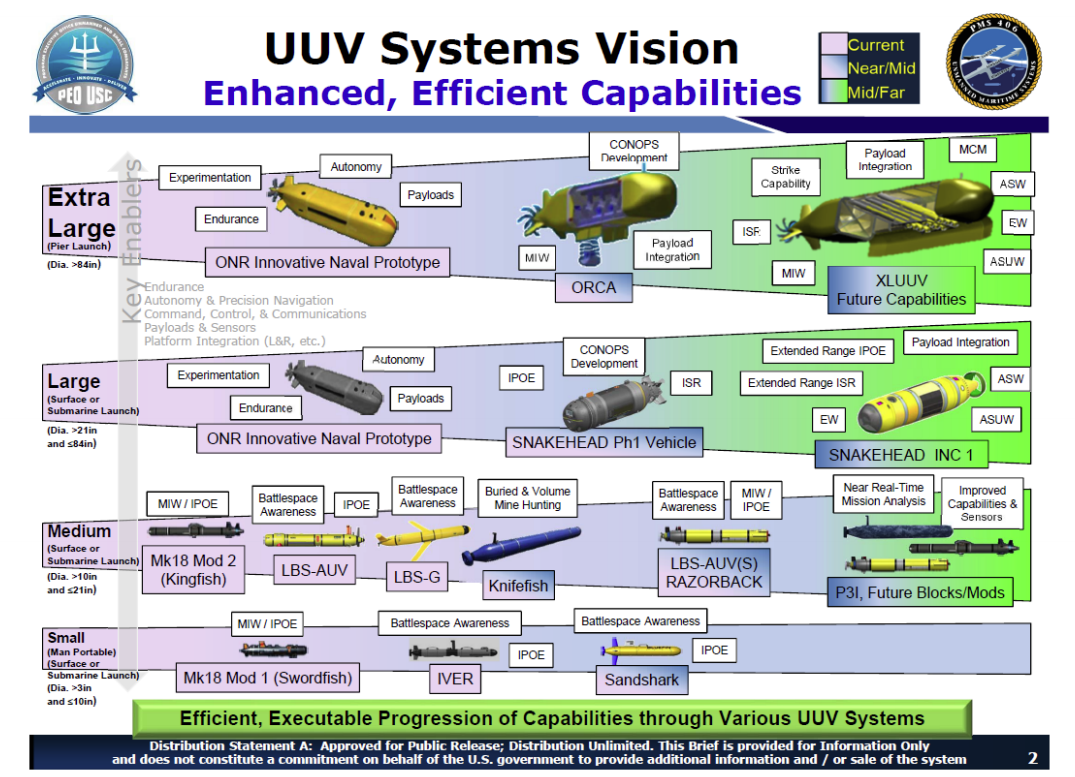

Through engagement with this group, Small said the Navy has refined and published several UMAA products, including an architecture description document that provides a high-level view of how to organize services and categories of autonomy code, as well as interface control documents for eight categories of services. With those ICDs now published, they’ve been invoked in contract documents for the Medium and Large USV programs and the Razorback UUV, and will be included when the Navy contracts for the Snakehead Large UUV next year.

Both the USV and UUV portfolios are contained almost exclusively under Small’s office within the Program Executive Office for Unmanned and Small Combatants, but the Navy’s unmanned air systems fall under other program offices within Naval Air Systems Command.

Small said there was already some collaboration between his program office and NAVAIR, but he said RAIL would likely bring them even closer together.

“They’re also interested in this RAIL concept as well, and again, through some of the foundational larger Navy efforts, be it the Digital Warfare Office and the Digital Integration Support Cell, there’s some kind of leveling efforts going on in the Navy that are drawing us closer together,” he said, adding that his office is also working with the Air Force to leverage investments they’ve made in modern software-development tools and processes.

“A place like the RAIL is really the convergence zone in the future for all of those things to come together and to be able to take advantage of collaboration,” Small said.