The ship maintenance contracting strategy the Navy adopted in 2015 has addressed many quality and cost challenges the service had faced, but the Navy continues to see schedule overruns despite the other benefits of the Multiple Award Contract-Multi Order (MAC-MO) contracting approach, the Government Accountability Office found in a new report.

However, the Navy is in the midst of several efforts to address on-time delivery of ships from maintenance availabilities – which service officials have said could lead to 71 percent of surface ships coming out of private yard availabilities on time this year, up from about 30 percent just two years ago – and the GAO noted it would be watching to see the results of these efforts.

“In 2015, the Navy changed how it contracts for (surface ship) maintenance work, aiming to better control costs and improve quality. The new approach, called MAC-MO, generally uses firm-fixed-price contract delivery orders for individual ship availabilities competed among pre-qualified contractors at Navy regional maintenance centers,” the GAO wrote of the MAC-MO approach. In contrast, under the old Multi-Ship/Multi-Option (MSMO) strategy, one contractor might be awarded all maintenance work for cruisers in a particular homeport, for example, and would be paid based on cost incurred rather than an agreed-upon fixed price.

“Since shifting to the Multiple Award Contract-Multi Order (MAC-MO) contracting approach for ship maintenance work in 2015, the Navy has increased competition opportunities, gained flexibility to ensure quality of work, and limited cost growth, but schedule delays persist. During this period, 21 of 41 ship maintenance periods, called availabilities, for major repair work cost less than initially estimated, and average cost growth across the 41 availabilities was 5 percent. Schedule outcomes were less positive and Navy regional maintenance centers varied in their performance,” the report notes.

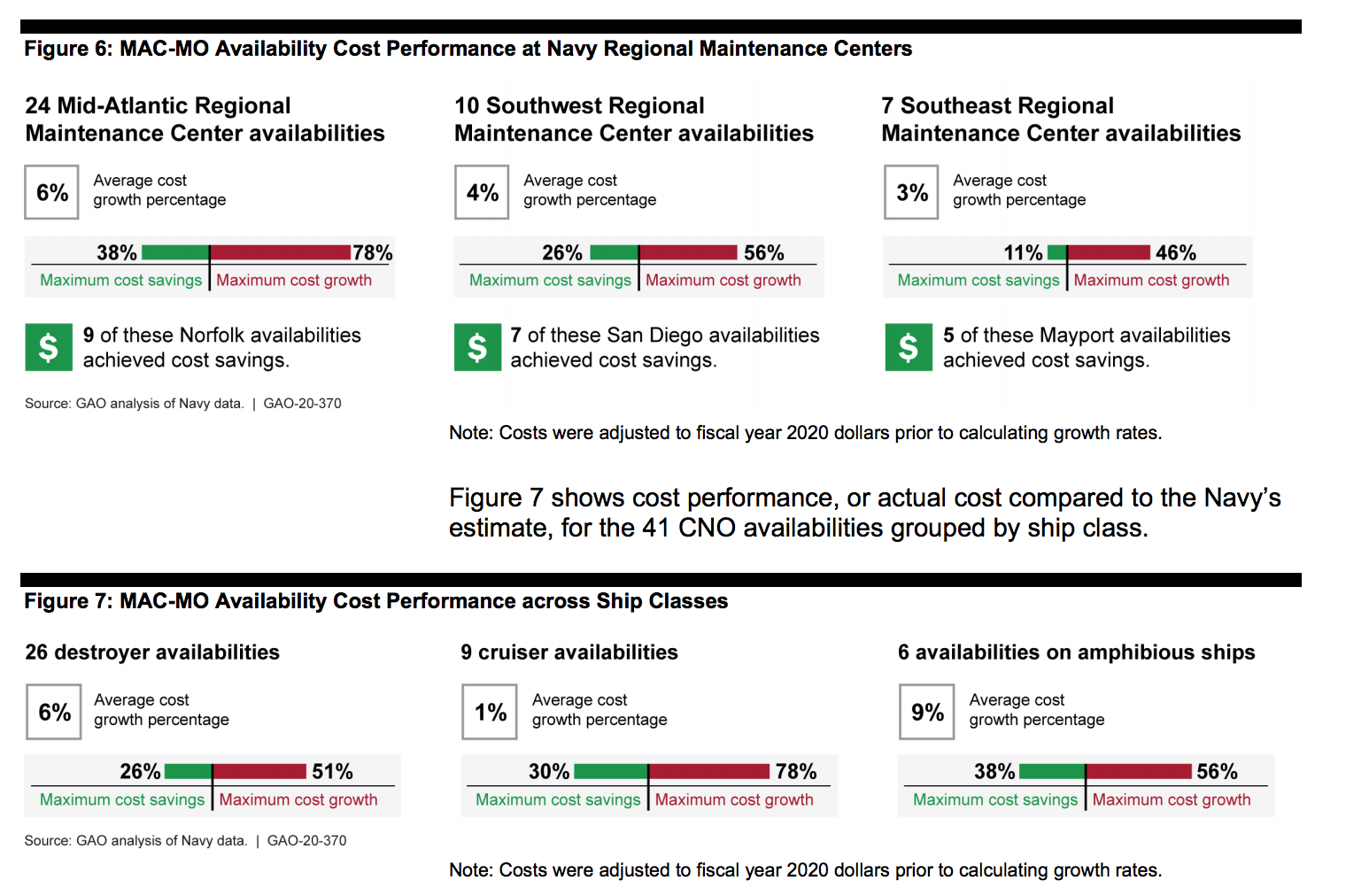

On the positive side, the GAO report noted improvements in cost performance at the three major regional maintenance centers: Southeast RMC around Mayport, Fla.; Mid-Atlantic RMC around Norfolk, Va.; and Southwest RMC around San Diego, Calif.

Overall, “between April 2015, when the Navy implemented the MAC-MO strategy, and April 2019, the Navy completed 41 CNO availabilities with an average cost growth per availability of 5 percent, or $1.7 million in fiscal year 2020 dollars. However, more than half of these availabilities (21 of 41) were completed at a lower cost than the Navy initially estimated. The cost growth of the remaining CNO availabilities (20 of 41) ranged between 1 percent and 78 percent and drove the aggregate average increase,” reads the report.

Specifically, five of seven availabilities in Mayport achieved cost savings, as did seven of 10 in San Diego and nine of 24 in Norfolk. One availability in Norfolk saw a 38-percent cost reduction compared to planned cost – though on the other side, an availability at Norfolk also came in at 78-percent higher than its planned cost, contributing to the slight cost growth for the average availability.

Specifically, five of seven availabilities in Mayport achieved cost savings, as did seven of 10 in San Diego and nine of 24 in Norfolk. One availability in Norfolk saw a 38-percent cost reduction compared to planned cost – though on the other side, an availability at Norfolk also came in at 78-percent higher than its planned cost, contributing to the slight cost growth for the average availability.

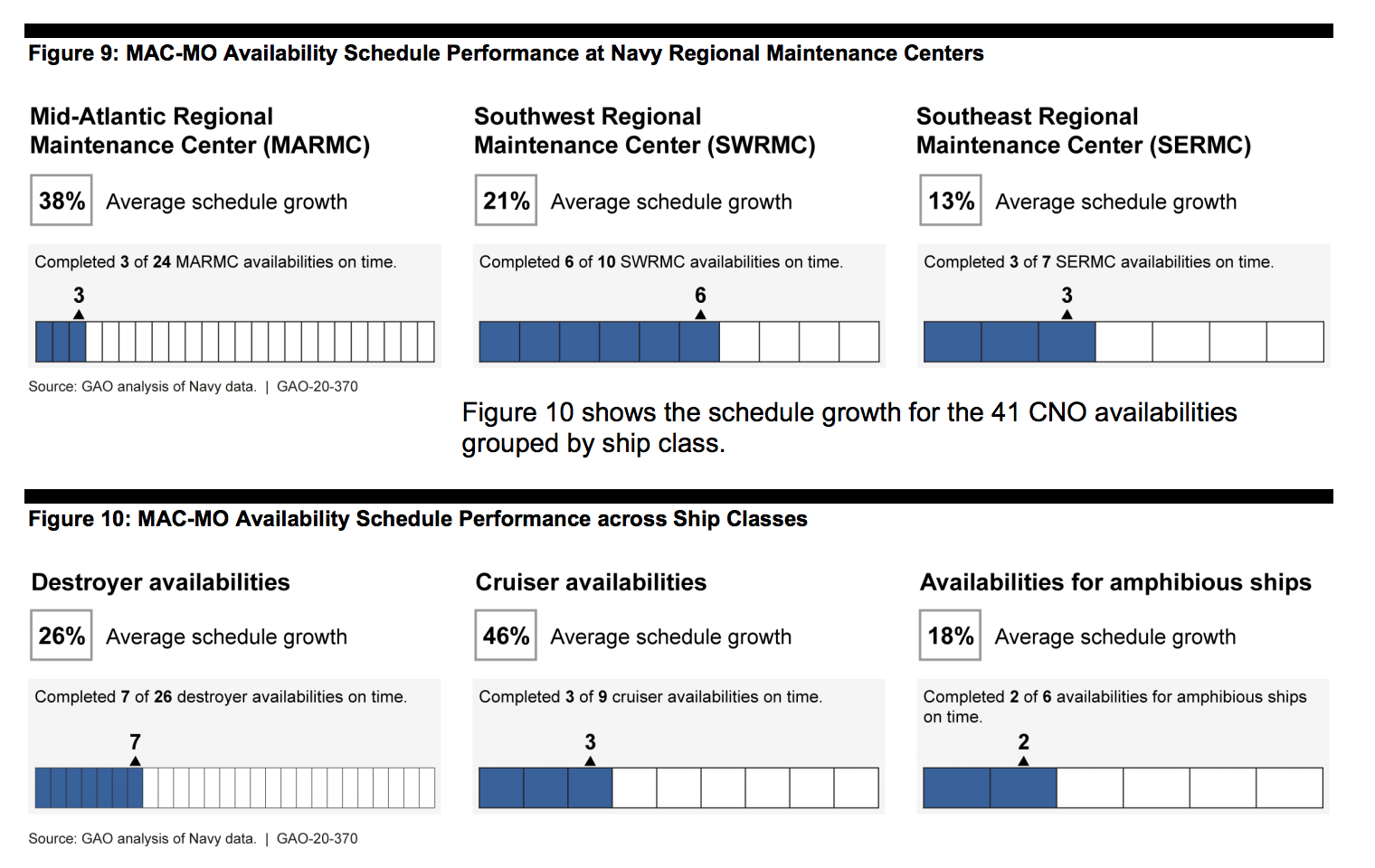

Schedule, though, remained an issue. Just three of 24 availabilities in Norfolk came out on time, along with three of seven in Mayport and six of 10 in San Diego. By ship type, only seven of 26 destroyers came out of maintenance on time, with the average DDG maintenance availability seeing 26 percent schedule growth. Two of six amphibious ships came out on time with a smaller schedule growth of 18 percent. For cruisers, three of nine CGs came out on time, but the class saw a 46-percent increase in the duration of maintenance availabilities compared to planned schedules.

“Navy officials stated that one potential source of delays is unplanned work, which consists of both growth work and new work. The Navy defines growth work as additional work that is identified or authorized after contract award that is related to a work item included in the original contract. We previously found that growth work contributed to cost and schedule increases, and it remains a contributing factor. Navy officials stated they expect some growth work in availabilities, as officials stated that certain tasks are difficult to fully scope within the original contract,” reads the GAO report.

“Navy officials stated that one potential source of delays is unplanned work, which consists of both growth work and new work. The Navy defines growth work as additional work that is identified or authorized after contract award that is related to a work item included in the original contract. We previously found that growth work contributed to cost and schedule increases, and it remains a contributing factor. Navy officials stated they expect some growth work in availabilities, as officials stated that certain tasks are difficult to fully scope within the original contract,” reads the GAO report.

The Navy has taken several steps to address the issue of growth work, which it recognizes as a key contributor to late deliveries, as well as other barriers to on-time delivery.

One change last year was awarding contracts 120 days ahead of the start of work instead of 60 days, and striving to have all material on hand 30 days before work starts. Where there are material challenges, RMCs are encouraged to look at materials from a regional perspective rather than a ship-set perspective.

“I’ll give you an example: if I have an availability that’s going on, and I need a certain valve, and that valve is late – but I have an availability that’s starting a little bit later and that valve’s already in the box – before, we weren’t going to that other box and taking the valve and using it” because ship sets were looked at individually instead of as assets for the whole RMC to tap into, Commander of Naval Regional Maintenance Centers Rear Adm. Tom Anderson told USNI News earlier this year. “So the focus we have on material is one part of” the drive to reach the 71-percent on-time maintenance goal this year.

Additionally, a pilot program in U.S. Pacific Fleet is allowing maintenance dollars to be used for three years, rather than the one-year money the Navy typically has to work with for operations and maintenance activities. The GAO report elaborated on the challenges surrounding the one-year money, noting that “if an availability extends into a new fiscal year and needs more than $4 million in additional prior-year funding, both Navy and Defense Department approvals are required. GAO found this approval process took between 26 and 189 days based on Defense Department data. In December 2019, Congress established a pilot program that would potentially allow the Navy to avoid this process” and therefore save precious weeks and even months waiting on permission to spend maintenance money that expired.

Additionally, the Navy has promised to work with contractors, some of whom do not like the MAC-MO structure and would prefer the old MSMO setup. These repair companies have told USNI News that the MSMO strategy allowed them to know they’d have all the cruiser work in San Diego, for example – meaning they had the visibility into their future work to accurately order parts and hire to the right workforce levels, and they could invest in equipment and training to specialize in repairs for that particular ship class. Now, future workload is less certain and the yards don’t develop specialties in a ship class, making future planning a harder for them.

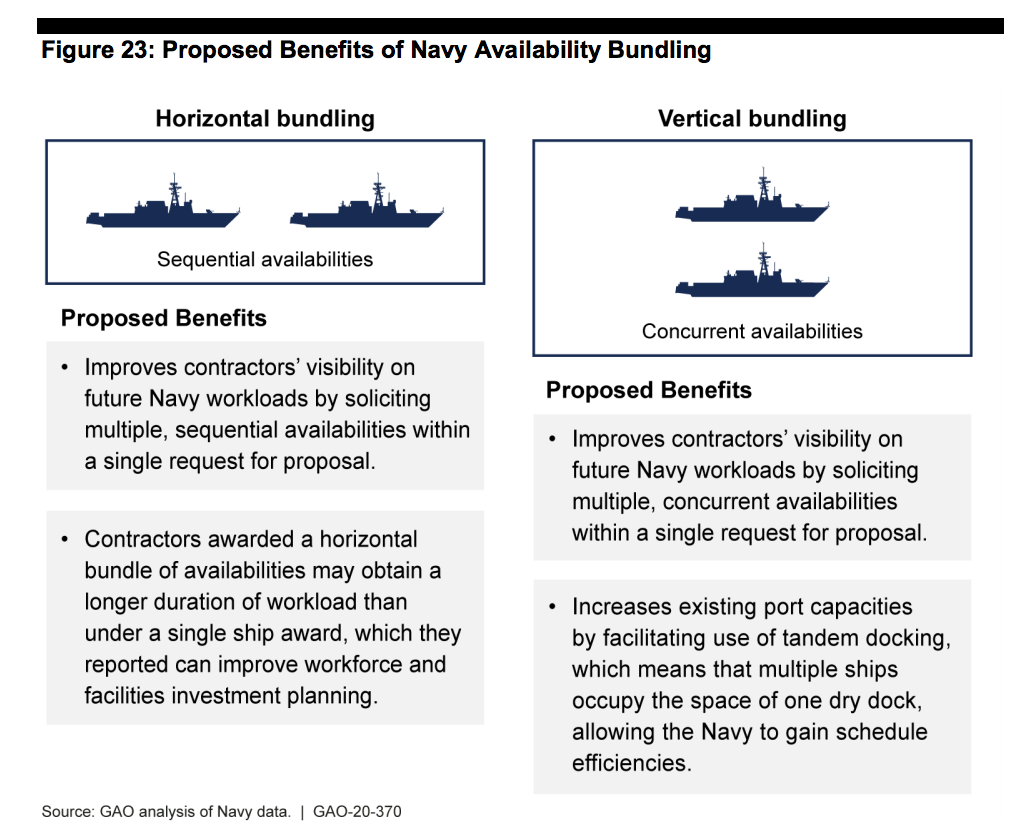

The Navy has said it would find ways to work to bundle availabilities – vertical bundles, as the GAO noted, where two concurrent availabilities are awarded, perhaps double-docking the ships as the SWRMC started doing with destroyers in San Diego – or horizontal bundling by awarding sequential availabilities to a yard.

The Navy has said it would find ways to work to bundle availabilities – vertical bundles, as the GAO noted, where two concurrent availabilities are awarded, perhaps double-docking the ships as the SWRMC started doing with destroyers in San Diego – or horizontal bundling by awarding sequential availabilities to a yard.