As the 1918 flu pandemic raged, Navy doctors preached that the rawest recruits and most senior flag officers needed to wash their hands often and to isolate the sick from the healthy, medical historians told USNI News.

Despite its best efforts, Navy medicine had mixed success containing the epidemic, the service’s reports from the time show.

In 1918, Naval medical facilities admitted 121,225 Navy and Marine Corps patients with influenza. Of these patients, 4,158 died of the virus. Sick patients spent more than one million sick days in these facilities worldwide.

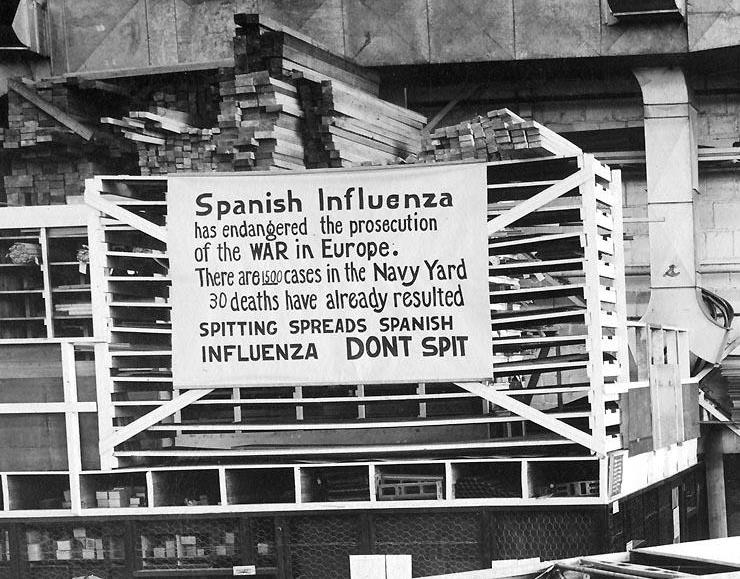

Navy medical personnel were familiar with smart practices, like decrying sailors’ “promiscuous spitting,” to keep hygiene and sanitation standards high and to reduce the risk of contagion, Andre Sobocinski, the historian manager with the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, told USNI News.

Medical personnel used circulars and medical notes on outbreaks to keep up to date with best practices. The medical providers studied influenza treatments but also the work to care for patients with pneumonia, diphtheria and meningitis.

Still, even with access to the best information available at the time, Navy medicine had to face the realities of the world around them.

“Crowding is the issue” that causes the rapid spread of infectious diseases, retired Capt. Thomas Snyder, executive director of the Society for the History of Navy Medicine, said in an interview with USNI News.

In World War I America, there were movies drawing crowds, large ballrooms for dancing and huge war bond rallies that fueled the influenza outbreak. By 1918, influenza was helped spread from place to place by the way Americans were moving about the country in much higher numbers than they had at the dawn of the 20th century. Much of this movement is attributed to the wartime movement of soldiers, sailors, Marines, and Coast Guardsmen from training bases to installations to embarkation ports along the East and Gulf coasts for France.

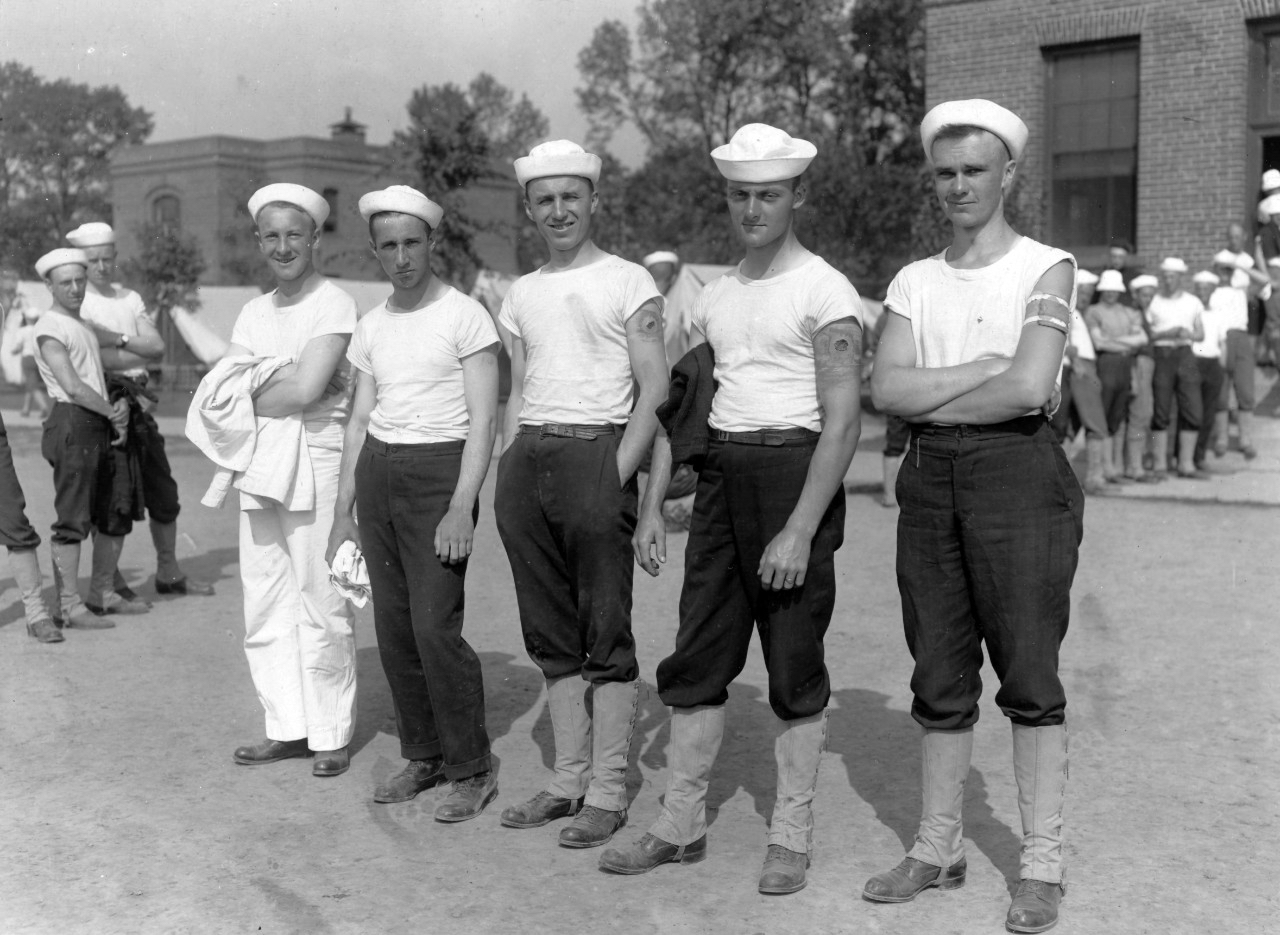

For recruits, often a draftee into the Navy and the Marine Corps, their first step in the training pipeline meant several days aboard a packed train to reach Pelham Bay, N.Y., or Puget Sound, Wash., for future sailors and Parris Island, S.C., or Mare Island, Calif., for future Marines.

The long rides became Petri dishes to spread the flu.

As the surgeon general reported to Congress after the war, “the conditions under which drafts are moved by rail, more especially for long distances, almost always involve such predisposing influences as overcrowding, bad ventilation, interrupted sleep, and irregular meals, and frequently poorly-heated cars in cold weather.”

In September 1918, as the outbreak was first being noticed, the Marine Corps stopped accepting volunteers, but did accept 15,000 draftees, Annette Amerman, a historian at the Marine Corps’ historical reference branch at Quantico, said in an e-mail.

“A good way to see the expansion is through the end strengths” on April 6, 1917, and December 11, 1918, Amerman said. In the month the United States entered the war, there were 13,725 officers and enlisted men in the Marines. In December, a month after the Armistice was signed, there were 75,101 officers and enlisted men in the Marines.

When the epidemic hit the sea services ashore and afloat, the outbreaks happened randomly in time and place. When the epidemic did hit a location, though, “there weren’t enough beds” in the clinics and hospitals, Snyder said. Civilian medical practitioners and facilities were also overwhelmed.

In boot camps and stations, “sneeze screens” were installed in open-bay barracks and “tent cities” and special barracks were established to isolate those with symptoms from the healthy, Sobocinski said.

“The beds in the hospitals were for the really sick,” Snyder added.

Success in containing the epidemic varied from station to station, Sobocinski and Snyder said. The impact of the epidemic was usually greater on large installations than smaller ones, according to the surgeon general’s report. As for recruits in boot camp, Amerman and Sobocinski said there is no evidence the military changed its training regime or altered the training length.

“The one change that I could find recorded was that officer training was extended by weeks late in 1918 as the flu made its way through Quantico,” Amerman wrote. As for Marine boots who became sick and missed weeks of training, she added, “a review of the muster rolls shows that the staff of the recruit depots were returned to duty, and that recruits listed as sick were not always transferred permanently out or discharged — some returned to their original companies, and some were returned to different companies after being in the hospital.”

Sobocinski said, “inoculations, serums, sprays, restrictions on liberty all seemed to have little impact.”

The surgeon general’s reported on the different experiences of sailors housed in a Brooklyn armory awaiting orders and those at a boot camp and detention facility at Pelham Bay.

The Pelham Bay facility was modern, well-ventilated barracks, separate dispensaries and operated under a modified quarantine. In contrast, the armory was “in a thickly settled” city neighborhood with a “constantly shifting” complement of 1,700 sailors and no restrictions on liberty.

“According to all the tenets of epidemiology, this station should have suffered worse than the training camp at Pelham Bay Park,” the surgeon general reported. Instead, the camp “furnished an example of the apparent futility of preventive measures in influenza.”

“Transports were often crowded with the sick and the dead,” as they steamed to Europe. Vice Adm. Robert Greaves, commanding convoy operations in the North Atlantic, wrote even with strict precautions aboard ships, “8.8 percent of troops transported during the epidemic” came down with flu or influenza with the numbers about the same for the sailors on those ships. Still, the number of deaths per thousand was dramatically different. “Navy death rate 1.7 percent” versus 5.7 for the soldiers, wrote historian William Still in his Crisis at Sea account of the pandemic and the impact of the “Spanish Lady,” “Flanders Fever,” and the grippe on the Navy’s operations worldwide.

Still quotes Marine Corps. Brig. Gen. Smedley Butler, who described how the epidemic swept onto transports carrying Marines. “We had a hell of a trip over, an epidemic of Spanish influenza breaking out among us,” Butler reported 500 cases aboard his ship during his crossing to France, according to Still.

Snyder, in the telephone interview, said the tight quarters for the troops being transported overseas contributed to the spread of influenza.

Epidemic on base, at sea and in war zones

As the epidemic spread into the war zone, naval air stations in France and the London headquarters of Adm. William Sims, senior American naval officer in Europe, reported outbreaks and the steps taken to control its spread. The Navy curtailed liberty and employed some “distancing measures” like closing YMCAs and canceling off-base athletic events. The Navy promoted cleaning surfaces with disinfectants, used nasal sprays and offered shots of whiskey to sailors and officers.

U.S. naval forces on battleships and other vessels concentrated near Berehaven in Bantry Bay in Ireland were especially hard-hit. There was a lack of adequate medical facilities that required the Red Cross to dispatch from Great Britain a 25-bed hospital with supplies and equipment to Bantry Bay.

A sailor aboard battleship USS Nevada (BB-36), one of the ships at Berehaven, reported sickbay lines of between 50-feet and 60-feet long. “One can tell by the expression on each face that they are battling to their utmost” to not come down with the flu and continue working. There were seven deaths among crew members during the week of October 25, according to Sims report.

“Probably the submarines based at Bantry Bay, Ireland, were the hardest hit. …On several of the boats from a third to a half of the small crews were infected,” according to the Sims report. Yet the submarines continued patrolling, but often having to run on the surface.

Ships in the Mediterranean Sea were not immune to the flu. USS Chester (CS-1) continued its convoy duty despite having “more than 100 men [in] the sickbay and hammocks that day, seriously crippling the working personnel” when it met the seven ships to be escorted.

Interestingly, one boot Navy boot camp, Yerba Buena, an island halfway between Oakland and San Francisco, reachable only by tug reported no outbreaks at the height of the epidemic, Secretary of the Navy and Navy Surgeon Generals told Congress in 1919.

Snyder, who lives relatively close to the small island in Vallejo, Calif., said in the telephone interview, “nobody left; nobody got on.” There were about 6,000 people on the island then, but “all interactions with others living in the Bay Area were halted except to receive supplies.”

“Social distancing was the 20-foot rule for the tug crews and sailors on the island,” Snyder. Gauze masks and sprays were the orders of the day for the crews. For those arriving on orders, there was a strict quarantine on the island as well.

To keep morale up during their enforced isolation, “sailors, officers and civilians on Yerba Buena Island organized their own entertainment, such as circuses and festivals,” he wrote. They even staged a carnival that turned the facility into “a miniature Coney Island.”

As the epidemic eased on the peninsula and in the East Bay, the quarantine was lifted. “Soon enough, Yerba Buena reported its first case,” Snyder said.

As for lessons learned that could be applied to today’s sea services, Sobocinski said there was a Navy laboratory established by a doctor at the University of California, Berkeley, based on his experiences with influenza between the wars. The lab continued its work into the 1970s.

“There’s something of a silencing of the history of the experiences” that go beyond looking at the records of the influenza epidemic of 1918. Other flu epidemics that could be studied now would include “Asian Flu” of 1957-1958, “Hong Kong flu” a decade later and more, Sobocinski said.

When asked about studying polio, which was an extremely fast-spreading and crippling viral infection until a vaccine was developed in the 1950s, Sobocinski said, “no one is touching that yet” as a research topic for lessons learned applicable to 2020.