Ten years ago, on Jan. 14, 2006, lead ship USS San Antonio (LPD-17) was commissioned as a Navy warship. But the immediate future looked bleak for the amphibious transport dock program.

Hurricane Katrina had struck four and a half months earlier, devastating the Ingalls Shipbuilding yard in Pascagoula, Miss., and scattering the workforce at the Avondale Shipyard outside New Orleans. With only one ship delivered and four in varying states of completion, it was unclear how to regroup and rebuild to keep the program on track.

As those first five ships hit the fleet, problems arose—pipes cracked, engines failed and deployments were delayed and interrupted by emergent maintenance needs.

Still, the Navy and industry pushed through. The ships started coming through their trials with fewer and fewer issues, production grew more efficient and less expensive, and Congress decided to take advantage of the hot production line and add back the once-removed 12th ship in the class.

And now—after a long decade of ups and downs—the San Antonio-class ship hull is set to double its presence in the Fleet: the hull form was officially chosen as the basis for the LX(R) amphibious dock landing ship last year.

Navy and industry officials told USNI News it has been a long journey, but they always believed they had a winning ship design and were confident they could work through the rough start to come out the other side as a successful ship program. Program officials are now looking forward to wrapping up the LPD program, with three more ships to deliver, and moving forward with the LPD-based LX(R).

A Clean Sheet Design

The San Antonio-class amphibious transport dock program was designed from the start to support Marines, Jay Stefany told USNI News in a Nov. 30 interview. He served as LPD-17-class program manager and deputy program manager from 2004 to 2012.

Every feature on the ship was designed for Marines: The ship had wider passageways for ground troops and all their gear, the aviation maintenance area and flight deck would accommodate the then-new MV-22 Osprey, berthing areas were larger for a higher quality of life, and the command and control suite more closely resembled that of a big-deck amphibious assault ship. These ships would not only replace the old Austin-class LPDs, the LKA amphibious cargo ships and LST tank landing ships – they would add command and control, medical spaces and reconfigurable spaces to be a state-of-the-art Marine weapon.

“Why do the Marines like it so much? Because it was designed for them from scratch. And that was always the goal,” said Stefany, who now serves as executive director of the Amphibious, Auxiliary and Sealift Office.

The Navy at the time was in the midst of trying out some new ideas—some of which worked for the LPDs, some of which didn’t, said LPD-17 deputy program manager Marianne Lyons, in the same interview. Lyons has worked in the LPD program office from 1995–2001, 2003–2007 and 2011 to the present.

When Avondale Alliance won the contract design award for the ship class in 1996, the Navy design team moved to Louisiana to be co-located with their industry counterparts, which Lyons said was helpful. However, the team relied on a new computer-aided design tool, which she said created some headaches.

The program then suffered a Nunn-McCurdy breach in 2002, when costs rose steeply on the first ship of the class, and there were some questions as to whether the program would be allowed to continue, Stefany said.

Despite that complication, Stefany and Lyons said the Navy team never gave up on the ship class because they believed in the quality of the design and its utility to the Marines.

“We still were committed to the program, I don’t think anybody was of the mind that the program was going to be canceled,” Lyons said.

Stefany said the program office had the attitude that “it’s still the ship we want.”

“I think we always thought there was a very good design, and there was never a doubt that in the end it would meet all the requirements the Marines had,” he added.

The First Five Ships

Just days after the crew of lead ship USS San Antonio (LPD-17) took delivery of its ship, Hurricane Katrina slammed into the Gulf Coast. The ship served as a base of operations to deliver humanitarian assistance and coordinate multi-agency government response efforts, Lyons said.

“To me, that was kind of a good success story,” she said.

The bad news: “At Ingalls, the shipyard facility was devastated. At Avondale, the people, the workforce, were devastated,” she said.

With the workforce scattered around the country, and major repairs needed at the yards, “you kind of have to step back and take a pause,” she said.

And while taking a pause was the only thing the Navy could do, it led to problems, Lyons and Stefany agreed.

USS New Orleans (LPD-18) was in the water at Avondale, USS Mesa Verde (LPD-19) was in the water at Ingalls, USS Green Bay (LPD-20) was being assembled on land at Avondale and USS New York (LPD-21) was in the early stages of construction at Ingalls when the hurricane hit, Stefany said. As a result of the post-Katrina cleanup, he added, “each of those ships was built in a different order.”

“The material for this step was missing, or the workers weren’t here for this step on this other ship. So it really took until [LPD] 22 where we could get back and say, ‘Let’s start with a plan and actually go step by step by step again.’ And then 23 we made the plan better, and 24, and I think 25 was the model plan I guess for building the ship. But 22 was the first one where we were able to, OK, let’s build it in a logical sequence now.”

Ingalls Shipbuilding Vice President of Program Management Richard Schenk said it was around that time that the shipyard could “stationize” the workflow—giving each employee the same repeatable task in each successive ship to increase quality and efficiency each time. That is a key tenet of manufacturing, but wasn’t possible in those first post-Katrina years, he said.

Stefany said this led to some general “quality issues” with hulls 18 through 21, which the industry team was able to fix once they could properly sequence the ships.

However, it would take more than proper sequencing to get the ships right. Even San Antonio, whose construction was not affected by the hurricane, had serious quality issues. The ship’s maiden deployment was delayed a couple of days when the stern gate had mechanical problems. Once under way, the ship was laid up in Bahrain to replace cracked pipes; engines failed when debris mixed in with the lube oil got into the engine and damaged gears; and before making it back home lost control in the Suez Canal when the port engine slipped into reverse and risked running aground.

Even during the worst of times for the program, Lyons said, the team still knew it had a good product to deliver to the fleet and the Marines, if all the design and quality problems could be brought under control.

“Ship design is hard, and there are always things that come up,” she said.

“There’s always good news and there’s bad news. So I think we just kind of took it as, ‘OK, this is a design issue or a quality issue that we need to address.’ And then you want to make sure that once you get that fixed, that you fold it into the ships you have under construction, and if there are ships out in service then you look to make sure that whatever fixes you do during new construction you can apply that fix to in-service.”

She said that despite the heavy scrutiny the ships came under every time one of them experienced a failure, the quality issues were “a small percentage to the overall success of the whole ship” and that Marines’ post-deployment reports had “glowing reviews” for the ship’s capabilities.

The Silver Lining

If something good came out of the damage Hurricane Katrina caused, it gave the shipyards a chance to renew their focus on quality and rebuild the yards in a way that would support more efficient LPD construction.

“I think Katrina helped force a culture-shift at the yard to really drive in first-time quality,” said LPD-17 Program Manager Capt. Darren Plath, who at the time was working with Ingalls Shipbuilding on the USS Makin Island (LHD-8).

Plath said during the interview that this renewed focus on quality spurred “inspection processes that were driven into the yard to make sure your pipe was capped on both ends when it was out in the pipe farm, vice letting a pipe sit, putting it on the ship, flushing the grit out; you’re keeping the grit out from the beginning. And I think that process went a long way to improving the quality areas that led to some engine issues.”

Plath said he could feel the beginnings of a corporate culture shift beginning in 2006 or 2007—after quality issues had arisen during ship trials but before San Antonio’s problem-filled maiden deployment.

Stefany said the LPD program office took note of the changes too.

“We’ve got to give the shipyard credit, too, their focus on quality and safety – they lost a bunch of money [because of the hurricane], and they weren’t focused so much on that,” he said.

“I think that mentality at the shipyard, which didn’t happen until that 2008–2009 timeframe, also contributed to, ‘Let’s get them built right. Let’s deliver quality products to the Fleet.’”

The Navy and industry team set up an LPD-17 Strike Team in 2008 to identify problems in the in-service vessels, adjust the ship design as needed to prevent failures in future ships, and find corrections to backfit into existing ships in the Fleet. Lyons said the Strike Team was involved in every leaky pipe, every engine failure, every mechanical failure, and “in time those issues become less and less and less.”

A Turning Point

After the strike team was stood up, and after the ships could be built in a properly sequenced process, the quality rose quickly. Lyons said the ships were delivered to the Navy with higher material readiness and fewer cards during the Board of Inspection and Survey (INSURV) test events.

For Plath, it became clearer that the ship program would not only get back on track, but could become something special for the Fleet. He said most of the issues that arose fell under the categories of design flaw or quality of production—and as the strike team refined the design and the shipyard addressed quality, the LPD “really ends up being probably one of the more successful designs I think we’ve seen in a while.”

Starting with USS San Diego (LPD-22), the first ship to make it through trials with no major issues, Lyons and Stefany said, the wins kept coming. The LPDs started taking on new missions no one could have expected early on, such as transporting terrorists captured in the Middle East to the United States for trial, or recovering NASA’s Orion spacecraft from the ocean.

Stefany said that all brand-new programs go through hard times in the beginning, but a key lesson learned on righting a troubled program is simply, “don’t let all the noise distract us.”

With such a large team—the shipbuilder, the Navy design team, the participating acquisition resource managers (PARMs), the shipbuilding supervisors—there’s a real challenge “to keep them focused on that big objective: We’re here to provide this capability to the Marines, the design is a good design, so keep in essence the morale up and keep focused on what’s good about the program,” he said.

Ultimately, the ship program—which had gone from 12 ships to nine—was restored to 11 and then 12 again as the Navy and lawmakers saw an efficient production line that had rid itself of its previous quality and procedural problems.

Looking to Expand

Though the Navy did not officially agree to use the LPD hull as the basis of the LX(R) design until 2015, and the idea was not formally put into writing until 2011, Stefany said the idea first popped up around 2009.

“I think when the Navy said we’re going to go from nine to 11, I think at that point Navy leadership was like, ‘OK, we’ve gotten through the initial problems, the new class problems, and this is going somewhere, we’ll invest in two more of these,’” he said.

“I think that was kind of the time that [next was] ‘OK, then if it’s affordable enough we’ll keep going and do the LSD-41 replacement this way too.’ So I think that time was probably the mindset of the Navy, which might have been 2009–2010.”

When the analysis of alternatives guidance came out in 2011, one of the several options outlined to study was an LPD variant. But Stefany said the LPD variant idea already had a lot of support behind the scenes.

The decision to go to 11 ships was read as, “’We believe you’ve gotten it straight now.’ Big Navy says yep, let’s go, and it’s only logical—if it’s going well and the Fleet, the customer, likes it and you’ve gotten those growing pains out of the way, so to speak, why not keep going? And the only reason was cost.”

LX(R)’s Way Forward

Though cost initially looked like it could derail the LPD variant idea, Plath and his team have been hard at work retooling the LPD design to make it more affordable as the LSD dock landing ship replacement.

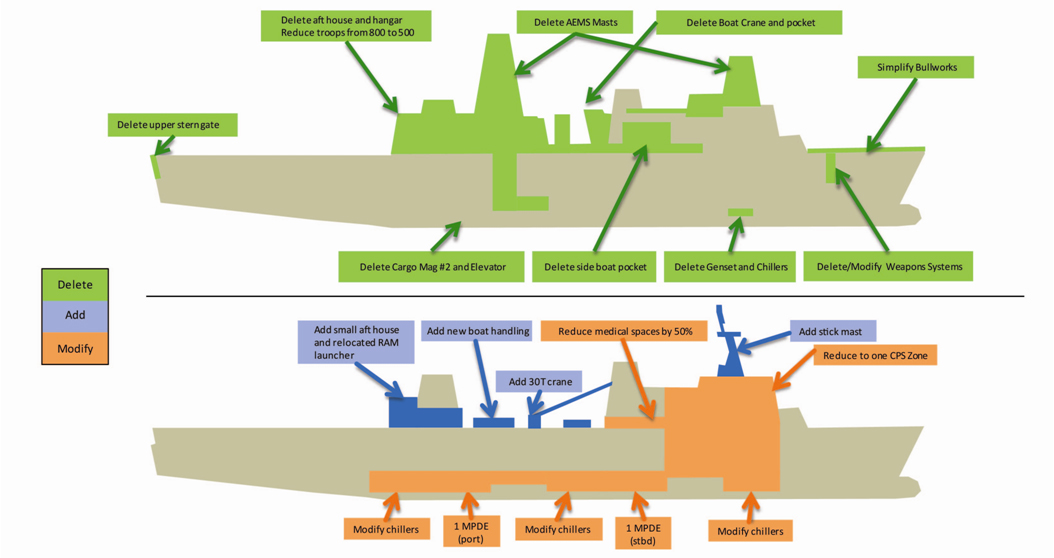

“We started identifying things we could take off, and using LPD-27’s material cost and LPD-25’s labor cost we kind of come up with a menu, if you will: If I remove this compartment, this item, we can save this much,” Plath said.

“It was about a 60-day effort, high intensity, a lot of energy focused on it, but we got close to our number and we weren’t quite there, so we were given some relief on the number of troops. So we were able to reduce or remove a lot of the aft superstructure. I will tell you, we worked with the Marines closely during this whole process, so a lot of back and forth with the Marine Corps, with the OPNAV sponsor, our ship design managers, to come up with ideas on what we could take off that would still have a functioning ship at the end.”

Plath said the design is not final yet, with the Navy expecting to hold a competition for contract design in the spring, but based on the major decisions that have already been made, “I think we found a configuration that is a feasible, functional design that both the Marine Corps and the Navy are happy with”—and for “basically the same amount of money as an LSD-41,” Stefany said.

The LX(R) will represent “a significant increase in capability and survivability from the LSDs. The communications suite that remains on the LX(R) is substantially better than the LSD, and the aviation capability, the hangar” will be much more advanced than what is on the legacy LSDs, Plath said.

Importantly, the LX(R), like the LPD, will be built to support split and disaggregated operations—where the three ships in an Amphibious Ready Group split up and take on missions in different parts of a theater or in different Combatant Commands.

Plath said this was one of the main sticking points with the Marines as Navy engineers scaled down the LPD design. The Marines wanted enough command and control capability, communications systems, aviation support, medical capabilities and other enablers to send the ship off on its own for an extended amount of time—which today’s LSDs cannot do.

The LX(R) hull is the same as the LPD hull, minus a few redundancies that were taken out for cost considerations, Stefany said. So while the hull is not considered as survivable as the LPD in terms of the redundancies built in, it is much more survivable than the LSD it is meant to replace. The same goes for the radar cross-section, Stefany said. Huntington Ingalls Industries’ Gulfport Composite Center of Excellence was shut down, so the LPD’s composite mast will be replaced with a traditional stick mast—“so again you’re in that in-between. If you’re looking at an LSD, this is a much more survivable ship. If you’re looking at LPD, it’s some areas equally, some areas maybe a little bit less survivable.”

Significantly, however, “I don’t think most people are going to notice a big difference between the ships, per se,” Plath said. The LPD and LX(R) designs will be so alike that they will leverage the same schoolhouses for crew training, and the maintenance plans will be very similar as well.

“Ideally, control systems and cyber and electronic upgrades we can do for LPD and LX(R) at the same time, if we do it right,” Stefany said.

That commonality might help the Navy field these ships faster by bypassing some requirements. For instance, because the hull will be the same as the LPD, Stefany said the program office is hoping to avoid doing another shock trial on the LX(R) and using the LPD shock-trial data instead.

ANCHORAGE, Alaska (May 4, 2013) Marines assigned to Task Force Denali run to bring the ship to life during the commissioning of the San Antonio-class amphibious transport dock ship USS Anchorage (LPD 23) at the Port of Anchorage. More than 4,000 people gathered to witness the ship’s commissioning in its namesake city of Anchorage, Alaska. Anchorage, the seventh San Antonio-class LPD, is the second ship to be named for the city and the first U.S. Navy ship to be commissioned in Alaska. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class James R. Evans/Released)

Ingalls Shipbuilding has not been selected to design or build the LX(R)—the company will have to compete with General Dynamics NASSCO for the work—but the yard is already viewing the last-in-class LPD-28 as a transition ship from the original LPD design to the LX(R), incorporating some design changes such as the stick mast.

And beyond LX(R), Ingalls Shipbuilding is not done with its LPD design, insisting the inherent flexibility has more to offer the Fleet. Schenk, the Ingalls Shipbuilding vice president, said the bells and whistles were taken off the LPD to create LX(R), and with another similar redesign effort the Navy could create a replacement for the 44-year-old LCC amphibious command ships. Or the Navy could create a ballistic-missile defense patrol ship in lieu of tying up four BMD destroyers to patrol the Mediterranean. Or a submarine tender. Or a hospital ship.

Schenk said the Navy has created multiple ships from a common hull design before and hopes the service will do it again.

“The original Aegis cruisers were going to be nuclear cruisers, and they realized that was going to be too expensive of a proposition, and they said ‘Well, we’ve got this great proven hull form in the 963s (Spruance-class destroyers), let’s see if we can make an Aegis cruiser out of it. And that’s exactly what happened. So there is precedent,” he said.

“The Arleigh Burke has the original flight, Flight II, Flight IIA and now we’re going to go to Flight III. Building new designs costs a lot of money, so take advantage of what you’ve got.”