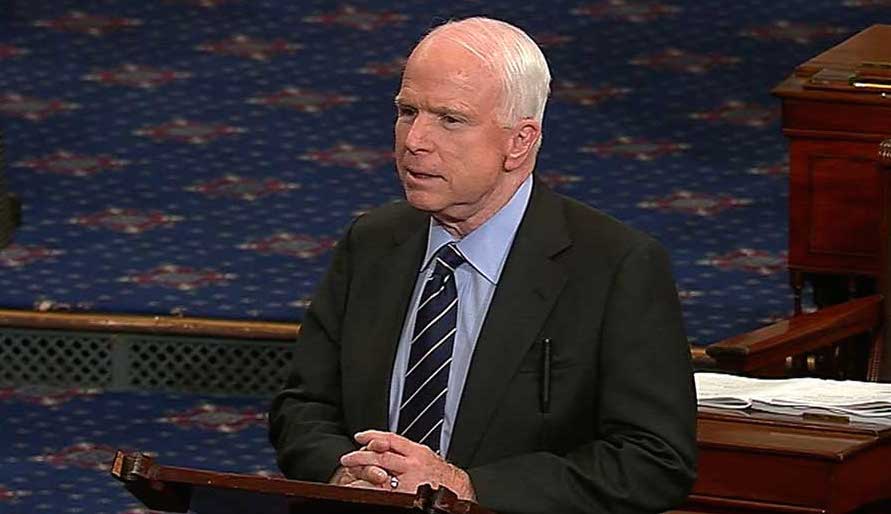

Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) delivered the following remarks on the Senate floor on the Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) program on April, 9 2014. A copy of the speech, as prepared, was provided to USNI News.

I rise today to bring attention to the Navy’s Littoral Combat Ship (LCS), a troubled major defense acquisition program that, if not properly addressed, will join a long list of failed procurements at the Department of Defense. From the thirteen arduous years that LCS has been in development, we have learned – yet again – an important, costly basic lesson: if we don’t know what we really want when we procure a weapon system, we’re likely not to like what we get … if we get anything. In this case, the Navy’s poor planning continues to frustrate its ability to state a clear role for LCS and has led to dramatic cost increases, years of wasted effort, and a ship that U.S. Pacific Command Commander Admiral Samuel Locklear recently conceded only ‘partially’ satisfies his operational requirements.

The list of how the LCS program has failed is ironic and, given the amount of taxpayers’ investment to date, shameful. In LCS, we have (1) a supposed warship that apparently can’t survive a hostile combat environment; (2) a program chosen for affordability that doubled in cost since inception and is subject to the risk of further cost growth as testing continues; (3) a ‘revolutionary’ design that somehow has managed to be inferior to what came before it on important performance measures; and (4) a system designed for flexibility that cannot successfully demonstrate its most important warfighting functions.

Poor Planning Led to Confusion and Cost Increases

Like so many major programs that preceded it, LCS’s failure followed predictably from a chronic lack of careful planning from its very outset in three key areas: undefined requirements, unrealistic initial cost estimates, and unreliable assessments of technological- and integration-risk.

In 2002, the Navy submitted its first request to Congress to authorize funding for the LCS program. Yet, even then, the program’s lack of defined requirements drew criticism from the Armed Services Committee conferees. The conferees noted that ‘LCS has not been vetted through the [Pentagon’s top requirements-setting body, called the] Joint Requirements Oversight Council’ and that ‘the Navy’s strategy for the LCS does not clearly identify the plan and funding for development and evaluation of the mission packages upon which the operational capabilities of LCS will depend.’ Despite the conferees’ concerns, Congress approved funding for the LCS program and authorized hundreds of millions of dollars for a program without well-defined, ‘frozen’ requirements. The Navy, therefore, charged ahead with production without a stable design or realistic cost estimates. That resulted in frequent, costly changes to the ships even as they were being built.

Originally, the Navy wanted a small, fast, affordable ship to augment larger ships in the fleet. With several interchangeable plug-and-play ‘mission modules’ that would be used with aluminum- and, separately, steel-hull seaframes, LCS was to serve multiple roles, operating in coastal or open waters as part of a larger battle force. The Navy could have easily procured a small warship similar to those already serving in naval fleets around the world. The capabilities of such ships were well-known at the time and would have required much less development. The Navy could also have upgraded older ships with a proven track record. Without any formal analysis of those reasonable alternatives, the Navy opted instead to develop a high-risk ‘revolutionary’ ship that bore little resemblance to anything else in the fleet.

Despite the foreseeable costs of building LCS seaframes while development was still ongoing, LCS’s original cost estimates were overly optimistic. Navy officials have since characterized those estimates as ‘more of a hopeful forcing function than a realistic appraisal of likely costs.’ While hope for low costs may spring eternal, reality is a far more helpful basis for generating cost estimates. In this case, a realistic estimate would have allowed legislators – and top defense acquisition managers alike – to make much more informed decisions on procuring LCS.

But, because of poor planning early in the program, LCS suffered through years of waste while demonstrating little in the way of desired combat capability. Hundreds of millions of dollars continued to pour into LCS each year even though the program continually failed to deliver useful capability or conclusively flesh-out the ship’s unstable design. Finally, in 2007, Secretary of the Navy Donald Winter identified the need to slow-down production so that a clear LCS design could be established and fixed-price agreements could be pursued before more taxpayer dollars were wasted. I strongly supported Secretary Winter’s actions, and I still believe that he effectively highlighted the extent to which LCS was slipping out of control.

It was not until 2010, however, that the Navy ultimately began to implement guidelines to bring skyrocketing LCS costs under control. With congressional approval, the Navy overhauled and restructured the LCS program and, since then, the cost of building LCS’s seaframes has finally stabilized. But, even though the Navy has stabilized those costs, the large investments sunk into the program to date have still not yielded commensurate combat capability.

Since the early stages of LCS procurement, I have attempted to shine a light on the lack of planning that has plagued the program. Last year, I authored legislation to reduce LCS production and require validation by DOD and the Navy that the program’s seaframes and mission packages are on schedule and would meet the capability requirements of combatant commanders prior to additional funding. Congress spoke resolutely on the issue, approving my proposed legislation and sending a clear message that LCS would need to justify its existence with meaningful progress toward becoming operational.

Continued Lack of Capability in the Program Suggests Need to Slow Procurement

Despite that the cost to complete the construction of the seaframes has stabilized over the past few years, LCS continues to face another potentially crippling consequence of poor planning – a serious lack in capability. Just last month, Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel identified this problem while announcing that the President’s budget request for fiscal year 2015 would reduce LCS production by forty percent, from 52 ships to 32 ships. Secretary Hagel said, ‘The LCS was designed to perform certain missions – such as mine-sweeping and anti-submarine warfare – in a relatively permissive environment. But we need to closely examine whether the LCS has the independent protection and firepower to operate and survive against a more advanced military adversary and emerging new technologies, especially in the Asia Pacific.’

Other Department of Defense leaders have expressed similar doubts about LCS’s ability to survive combat situations. Acting Deputy Secretary of Defense Christine Fox said in a speech on February 11, 2014, ‘niche platforms that can conduct a certain mission in a permissive environment have a valuable place in the Navy’s inventory, yet we need more ships with the protection and firepower to survive against a more advanced military adversary.’

The prospect of sending LCS into combat with the lives of American sailors at risk is even more chilling in the aftermath of the Government Accountability Office’s (GAO) July 2013 report on LCS. Early in LCS’s development, the Navy intended for the ship to be a self-sufficient combatant that could engage in major combat operations and survive in a battlespace actively contested by enemy forces. According to GAO, however, more recent Navy assessments suggest that LCS has little chance of survival in a combat scenario. Instead, LCS can only be safely employed in a relatively benign, low-threat environment. GAO also found deficiencies in the ability of LCS to operate independently in combat, turning a supposedly capable warship into a vessel requiring significant support from larger ships of the fleet. Such fundamental uncertainty about LCS’s capacity to function as a warship in a combat environment demonstrates the lack of clarity regarding LCS’s actual capabilities.

Recent GAO assessments continue to highlight major problems regarding the LCS program. According to an article last Friday, a soon-to be released GAO report will validate the need for LCS to be subject to rigorous testing and evaluation – not just anecdotal lessons learned from a single overseas deployment. And, there is talk of another impending GAO report critical of LCS that will also likely echo the issues I have long cited that continue to plague this program.

GAO is not alone in expressing concern about LCS’s capabilities. In January 2014, the DOD Director of Operational Test and Evaluation published his annual report, and noted that weapons systems aboard each of the two LCS variants are struggling to demonstrate required capabilities. The report noted that ‘the Navy has not yet conducted comprehensive operational testing of the LCS’ and is ‘still developing the concept of employment for these ships in each of the mission areas.’

It’s worth taking a moment to step back and consider the absurdity of this situation. Planning and development of LCS has been going on for twelve years, roughly triple the time it took to fight and win the Second World War. In that time, the Navy has spent billions of dollars and failed to even figure out how to use the ships it is procuring once those ships demonstrate some semblance of capability. And, lest we forget, whether LCS will ultimately be operationally effective, suitable and survivable remains, at best, unclear. Failure this comprehensive is incredible, even for our broken defense procurement system.

The individual mission packages that were supposed to give LCS its real functionality in the fleet present another area of major concern. The LCS’s are meant to be outfitted with one of three interchangeable mission packages tailored for particular roles in the fleet – anti-submarine warfare, surface warfare, and mine countermeasures. So far, the mission packages have experienced significant performance issues.

The anti-submarine warfare mission package has suffered particularly severe setbacks in recent years. When the anti-submarine package was tested by the Navy, it actually demonstrated less capability than predecessor systems. The Navy subsequently cancelled the package and reportedly revised its entire strategy for procuring that aspect of LCS. The Navy has now stated a goal of fielding the anti-submarine mission package by 2018. But, no independent assessment has been performed to evaluate the likelihood that the Navy will meet that 2018 goal. And, the program’s performance to date, of course, does not fill me with confidence that the goal will be reached on schedule.

The other mission packages also have experienced major problems. The Navy has taken delivery of early versions of the surface warfare and mine warfare mission packages. But, according to GAO, both packages have experienced significant performance issues. And, neither has yet been fully integrated into the LCS seaframes.

“The mine countermeasures mission package, considered by many experts to be the most important, is more than four years behind schedule. According to the DOD’s Director of Operational Test and Evaluation, the mine countermeasures mission package has yet to demonstrate any of its required capabilities.

Given the utter failure of the mine countermeasures mission package to date, the Navy has altered its plan for acquiring this package. The full package will be delivered over a series of four increments and, if everything goes according to plan, the Navy will successfully demonstrate the capability of the fourth and final increment in 2019, eighteen years after planning for the LCS program commenced. Until then, the Navy will be forced to retain the current generation of minesweeping ships.

Today, the Navy plans to purchase its final LCS seaframe in 2019, the same year when the mine countermeasures package is supposed to be ready. If the mine countermeasures package has suffered a delay by that point – and with the history of this program to date, a mere one year delay would qualify as an improvement – the Navy will have an entire fleet of LCS’s with only two-thirds their planned capability, even if all of the other problems with the ships are fixed.

All of the mission packages need significant further testing and have to overcome major integration challenges. That work is likely to drive up program costs and leave combatant commanders without the tools or capabilities they need for years to come.

Production Shouldn’t Continue Until Capabilities are Better Developed

The LCS program faces a daunting combination of capability failures and strategic confusion. The Navy does not know what the LCS seaframes will actually be capable of doing once all of them are purchased in 2019, and it does not know what role they will play even if development miraculously goes according to plan. Against that backdrop, the need to slow this procurement is clear.

Recently, we learned that, at Secretary Hagel’s direction, the Navy has established a task force to determine how LCS can best serve the fleet going forward. The Navy should, above all else, not repeat the mistakes of the past, and Congress must hold the Navy to account at each step in the process. This means establishing requirements and sticking to them, setting a stable design and holding to it, and zealously guarding against further cost growth.

I support Secretary Hagel’s decision to limit LCS procurement to 32 ships. I have recommended further reducing LCS procurement to 24 ships. More important than the raw number of ships, however, is the manner in which the procurement goes forward. As Congress considers the President’s 2015 budget request and continues to conduct oversight of LCS and every major defense acquisition program, we would be wise to understand this particular program’s failings, or risk repeating them.

The program is still clearly riddled with uncertainty about what the ships will be used for and what they will be capable of. Production should not go forward until the Navy and DOD confirm that LCS provides greater capabilities than the legacy ships it is intended to replace and that the mission packages plus the seaframes have demonstrated the combined combat capability that our combatant commanders need.

I understand that, in connection with Secretary Hagel’s directive to limit LCS’ procurement and develop a more capable follow-on ship, the Navy is underway brainstorming on possible alternatives to LCS that may provide it reliably with the capabilities it needs at a comparable cost. Before making final decisions on any procurement, however, the Navy must first determine what problem it is trying to solve – exactly what operational requirements do combatant commanders actually have that cannot be met with current capabilities? This is the step that the LCS program originally skipped. Only after that basic question is answered definitively should the Navy start considering what ‘material solution’ should be brought to bear on that capability gap. On major defense acquisition programs, that should be our always be our approach – LCS or no LCS.

While the history of the LCS procurement supports my recommendation that we should not procure ships until we know what we want them to do, that outcome is also dictated by plain common sense. We live in an age of great fiscal uncertainty due to sequestration and other defense budget cuts. With that fiscal pressure, there is a much smaller margin for error in the procurement world. Every dollar wasted buying ships with unclear capabilities for unspecified missions is a dollar that could have supported a vital defense activity. The wastefulness of excessive concurrency – of buying a system that has not been tested and figuring out requirements and fixes on the fly – is more unacceptable than ever when so many good programs have to make do with sharply reduced funding. I will continue speaking out against wasteful concurrency, that is, ‘acquisition malpractice,’ as I have done for years.

In today’s fiscal world spending money as we’ve done in LCS is not just reckless, not just wasteful – it’s dangerous. It actually weakens our national defense. It is my sincere hope and firm conviction that in the future we can prove ourselves better stewards of taxpayers’ monies than we have in the past. And, finally getting LCS right would be a big – long-overdue – step in that direction.