On August 17, 1942 211 Marines set out from two submarines to Makin Island, the home of a Japanese seaplane base. The raid 70-years ago was a first for the U.S. and a precursor to U.S. Special Operations forces that operate routinely from submarine assets. This is a narrative of the raid originally published in the October, 1946 issue of Proceedings.

It was D-Day plus One in the Solomons. Three thousand miles away two submarines passed Hospital Point, Pearl Harbor, and headed out to sea.

U.S. Navy photo

Submarines often had silently left Hawaii and had as silently returned, their conning towers emblazoned with miniature Japanese flags, since the first days of the war. They would until the last. But none had left with such a cargo as these two on that August 8 of 1942.

A plane on patrol swooped low over the pair. To the pilot as he waggled his wings in a gesture of “Good Hunting!” they were as other submarines he had seen taking the great circle route westward. Could he have seen below those narrow decks into the strong pressure hulls, he would have snorted “what the hell are those ‘@#$%’ Marines up to now?”

For there were Marines in the two submarines — two hundred and twenty-two of them. But they weren’t taking over submarines, they were being taken by them — on a foray unique in American naval history.

This naval task force of submarines, Argonaut and Nautilus, was to carry out a daring raid on Makin Island, strategic atoll in the Marshalls. The purpose was manifold: to divert the enemy’s preoccupation with the Solomon’s invasion, to destroy installations and the Japanese garrison, and to secure, if possible, intelligence from prisoners and documents. The Second Marine Raider Battalion, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Evans F. Carlson, was assigned the job.

For eight days the submarines sailed eastward. It was hot and cramped in the close quarters. The temperature of the sea itself was 80 degrees , and although extra air-conditioning units had been installed, the temperature inside the submarines was raised over 90 degrees and the humidity to 85 percent by the sweating bodies of the jam-packed men. All torpedoes had been removed, except for those in the tubes, and bunks had been built in the forward and after torpedo rooms. To fit that many men in, the space between these bunks was so limited that if a man wanted to turn over, he had to slide out of his bed and crawl back up the other side!

Fortunately the weather was good, and so the men were able to go topside for exercise and fresh air, twice a day. A submarine is most vulnerable on the surface, so these periods — once in the morning and once at night — were timed carefully. It took four minutes for the marines to get on deck, and three minutes for them to get below again. They were allowed ten minutes in the fresh air. As they got within the radius of aircraft search of Makin, the morning airings were discontinued, but even until the night before the attack, the evening “breathers” were kept up. And as a result, the Marines reached their objective in excellent physical condition, although in a state of temper that boded ill for the Japanese.

Meals, too, were a problem. The galleys were in constant operation. Each meal required three and a half hours to serve, and baking had to be done at night. The men ate two meals a day, with crackers and soup at noon.

U.S. Naval Institute Archives

Each submarine headed toward Makin independently. Should the two submarines be detected by the enemy together, suspicions would be bred of an expedition in force. On the other hand, separated they could be evaluated only as submarines going to individual patrol stations.

The Nautilus, being the swifter of the two boats, was to go ahead as fast as possible and to make a periscope reconnaissance of the island before the day of the landing. It was to assay the preparations the Japanese might have made to forestall a landing, and to study the tides and currents around the atoll to insure a rapid and safe debarkation when the time came for the attack.

To do this, the Nautilus sped ahead, and on August 16, at three o’clock in the morning, she made landfall on Little Makin atoll. Creeping slowly at periscope depth along Makin Island during the morning and early afternoon, taking landmarks such as Ukianong Point on the south coast, and prominent trees, her commander plotted the tidal currents, and found them quite different from previous information. Immediately after dark he surfaced and, in the middle of a violent rain squall, made rendezvous with the Argonaut within fifteen minutes of the time originally scheduled.

“At the rendezvous,” said the captain of the latter, “we exchanged supplementary operation instructions concerning the expedition and its extension to Little Makin and two other islands if the circumstances permitted. The submarines then proceeded in company to the prescribed landing point off Makin Island, arriving at about 2:30 in the morning. The disembarkation started about 3 o’clock and in weather which was less favorable than we had encountered during rehearsal….“

For weeks the Marines had trained intensively at Midway and in the Hawaiian Islands. Night landings from submarines had been practiced on several occasions, as had the handling of rubber boats in surf.

The plan of attack called for all landing boats to assemble alongside the Nautilus so that they might get underway together for simultaneous landing on two separate beaches. The continuous noise from the wash of the swell through the Nautilus’ limber holes, and the roar of the surf, made it almost impossible to hear orders. And added to this, most of the outboard motors refused to start, and the swell of the sea made it difficult to keep the bubble-like rubber boats alongside the submarine.

Colonel Carlson, in trying to get his boats straightened out, was all over the topside of the submarine to form up those that had motors running to tow in others, and also to divide his forces into the prearranged two groups. Because of the confusion, the colonel made a quick change of plans and ‘Nord was passed that all boats were to land together in a body, and not at two separate beaches.

U.S. Naval Institute Archives

While this was going on, nobody noticed that Colonel Carlson’s own boat had drifted off, its motor drowned. Here were the troops in their boats, and the general, or colonel in this case, on board ship! Trying to call a boat alongside, he couldn’t make himself heard above the noise of the sea.

The captain of the Nautilus finally was able, with a megaphone, to bring one of the boats alongside and disembarked the colonel and his runner. The boat was not his, and after delivering the colonel to his own boat, it returned to the ship for instructions as to its proper landing place.

Not knowing the last minute change of plans, the captain of the Nautilus directed this boat to its previously assigned landing beach. It was the only boat of that contingent supposed to land in the rear of the Japs that actually did so ! The rest of them landed in front. But this boat load succeeded in raising so much Cain behind the Japs’ flank that it materially helped the major attack.

The landings in all cases were made easily through the surf without being detected by the enemy. A guard was posted, the boats hidden in the undergrowth above the beach, and before dawn the two companies had completed reorganization into their units. The two submarines got underway and moved four miles offshore, keeping contact with their former passengers by voice radio.

Despite the initial confusion in getting away from the submarines, the landing had gone well. Too well. For then the inevitable accident happened: an overeager Marine tested his rifle to see if it would work.

It did!

The alarm had been given and Colonel Carlson immediately sent Company A to cross the atoll, seize the road on the lagoon side, and then report where they were in respect to the wharves. Japanese defense positions, including a barb-wIre fence, a portable “hedgehog” road block, and four machine guns, had been placed 111 an easterly direction across the island. But our Marines were able to overrun the installations before the Japs were able to man them. By 0545 Lieutenant Merwin C. Plumley reported from the government wharf that his company had taken the government house, without opposition.

Our landing in the Solomons, coupled with the air and naval attacks on Kiska ten days earlier, bad disturbed and alerted the enemy on this little island. Natives, who were invariably friendly, told the Marines that maneuvers had been held by the defending forces in preparation for a raid, and snipers had strapped themselves to trees three days before our arrival. The Japanese reveille the morning of August 17th was at 0600, and upon the alarm they had rushed from their barracks. But Company A had by this time been deployed across the island and was advancing south. Company B being held in reserve on the left flank. Shortly after contact was made with the Japanese on the lagoon road, near the native hospital, our advance was halted by machine gun fire from the right flank. Some of the Japanese had come up on bicycles, others came by truck. Fire from our anti-tank rifles forced the latter to unload about 300 yards down the road, and by 0630 we were heavily engaged.

Snipers were a main problem, at first. Strapped to the heavy foliage of the palm trees, their jungle-green camouflage suits were hard to detect, and often the snipers could only be killed by the uneconomical method of shooting away the fronds that concealed them. Others were found because they moved after their fire indicated their position. One ingeniously tied the tops of two palms together so that when he knew he had been spotted, he cu t his trees a part, and the Marines didn’t know in which one he was.

Our radiomen were targets for snipers if they were seen using phones, and officers brought enemy fire if they used their hands or arms to direct their men. Officers soon learned to use voice signals entirely. Not knowing the action of a Garand rifle proved dangerous ignorance to many a Jap. After a Marine had fired, a sniper would frequently raise his head to take air, thinking our rifle had bolt action. The raiders were quick to show him his error!

Natives, who had moved north from Butaritari Village ahead of the Japanese, reported that the majority of the enemy was on On Chong’s Wharf, with others near Ukiangong Point on the lakes. So Lieutenant Colonel Carlson asked the submarines to open fire with their deck guns on this region.

U.S. Naval Institute Archives

The Nautilus, then heading southwest, complied almost immediately. “We fired about twelve salvos into this area,” said her captain. “During the firing however, no spots were received from the Marine observer because of communications difficulties. (The Jap was jamming our voice frequency.) We continued firing until the course of the submarines began to uncover the entrance to the lagoon. I then ordered a reversal of course, because our information led us to believe that the lagoon entrance was covered by a shore battery and I did not want to unmask this. Before we could complete reversal of course and again open fire on Ukiangong Point we received a request from Colonel Carlson to take under fire any ship in the lagoon 8,000 yards off On Chong’s wharf. This we complied with, but receiving no spots concerning the fall of our shot into the lagoon, we moved the salvos in deflection and range to cover approximately the area concerned. Subsequently we learned that in laddering these salvos around in this manner, the Japanese ships had gotten underway, steamed around the lagoon with a view to avoid the shot, and had run into two salvos and had been sunk….”

At 0902 the Argonaut suddenly submerged on a false plane contact and the Nautilus followed. They remained under water for about an hour, but shortly after resurfacing an enemy biplane was seen and the submarines went down again, staying this time for two hours.

On shore, the Marines were finding the going difficult. Here, as in the Solomons, the Japs fought to the last man, and the final wiping out had often to be done with knives.

A lieutenant with his unit of eleven men, which had landed behind the enemy, made the most of their opportunity to harass. Near the trading station they killed eight Japanese soldiers with the loss of three Marines. They burned a truck, destroyed a radio station, searched houses, and did other damage before struggling through the surf to the Nautilus that evening.

U.S. Naval Institute Archives

The Marines found willing allies on the island. The native police chief was handed a Garand to hold by a Marine, and he used it to kill two snipers. Some natives opened coconuts to relieve the men’s thirst, while others carried ammunition for the machine gunners. They gave useful-if not always reliable-information as to the presence of isolated enemy groups.

At 1130 two Japanese Navy reconnaissance planes flew over Makin for about fifteen minutes and dropped two bombs before leaving. At 1255 the Nautilus surfaced, but had to crash dive immediately when 12 shore-based bombers were seen approaching. Both submarines remained submerged for the rest of the day.

In the afternoon an attempt was made by the Japanese to reinforce Makin, and two planes carrying about 35 men landed in the lagoon. Both planes were destroyed by our machine gun fire.

During the day the Japanese attempted three counterattacks. After several minutes of yelling and shrieking to work up a fighting frame of mind, they came forward on the run, waving their rifles. Rifle fire quenched their exuberance, and in one instance a submachine gun killed eight Japs who came out bunched together. Warned by the noises, the Marines easily stopped these attacks.

In one instance the Japs gave us some welcome help. Before the last air attack at 1630 on August 17, the raiders had withdrawn about 200 yards in an attempt to lure the enemy from his positions. It didn’t work, but when the Jap bombers came over they bombed the area most strongly held by their own men, causing many casualties.

Rendezvous with the submarines had been set at after 1830, and no later than 2100. So at 1700 Lieutenant Colonel Carlson ordered a slow retirement and by 1900 the raiders were back at the beach.

Leaving the island had been timed to coincide with high tide and darkness, so the submarines could get as close as possible to the beach. It was realized that the men would be exhausted after the day’s heavy fighting, but the peculiar nature of the surf off the atoll had not been taken into account. The short, quick rollers made it virtually impossible to launch the rubber boats that had been dragged from the foliage where they had lain hidden all day. Gasoline motors refused to work, boats overturned, throwing men and equipment into the water. Even the loss of equipment and the jettisoning of motors didn’t help any. Furious paddling, at swimming with the boats in tow, accomplished nothing.

Only 53 men in four boats reached the Nautilus, and three boats the Argonaut during the night. About 120 raiders had to stay all night on the rainy beach. Half-clothed, almost entirely unarmed, and in a state of complete exhaustion, they had reached, as Lieutenant Colonel Carlson saId later, “the spiritual low point of the expedition.”

The captain of the Argonaut decided to send the two reserve landing boats ashore to help in bringing the men back. A few available arms were gathered together and five Marines, chosen from volunteers, elected to take the equipment in and assure the Marine commander that the submarines would remain indefinitely to get the men off, except as forced by planes to submerge during the day.

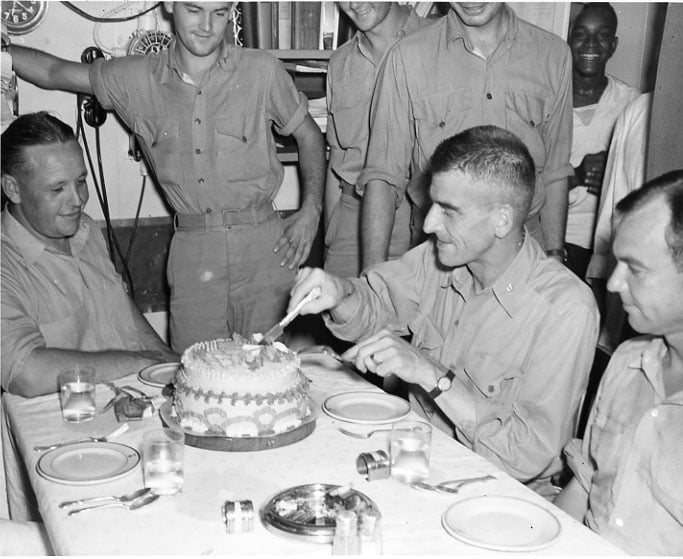

At daybreak they started in, and at the same time four boats managed to get to the two submarines from shore. In one of them rode a tall, bald, be-spectacled Major James Roosevelt, executive officer of the raiders and eldest son of the President. They just made it.

“Roosevelt was the last man out of the boat,” said the captain of the Argonaut, “and had just barely gotten his tail feathers down when the first Jap plane came over and the Argonaut had to go under. If the plane had appeared fifteen or twenty seconds earlier, I’m afraid Major Jimmie would have been swimming around in the Pacific.”

The planes severely strafed the volunteers’ boat, and only one man managed to get his message through to Colonel Carlson by swimming. The submarines remained submerged during the day.

Stranded ashore until nightfall, the Marines sent out patrols. Contrary to the impression received from the fighting the day before, it was found that few Japanese were still alive. Eighty-three enemy dead were counted, some near their machine guns and others behind palm trees which our guns had penetrated. Bodies were searched for papers, and equipment taken to rearm themselves. Only two snipers were encountered during the day; one near the north end of the atoll, and the other near On Chong’s Wharf. Both were shot. The defense force had numbered, therefore, only about 90 men.

Marine casualties from the two days’ fighting totaled 51, of whom 18 had been killed, including Captain Gerald P. Holtom, intelligence officer. Fourteen men were wounded, of whom two were officer. The missing totaled 12. Seven Marines were drowned trying to buck the surf.

Destruction of enemy installations 1J1≠cluded the firing of about 1,000 barrels of aviation gasoline, demolition of the main radio station at On Chong’s Wharf, and the destruction of other facilities and stores. A new-type machine gun mounted on a high and heavy tripod, apparently adaptable for anti-aircraft use, was found.

At dusk that night the submarines returned to the rendezvous, and Lieutenant Colonel Carlson signaled them to go to the lagoon entrance by 2130, as he thought the evacuation could be made more easily there.

The captain of the Argonaut was not satisfied that this message was bona fide. He had not received positive information that there were no shore batteries, and there was a possibility that the Japanese had taken Carlson prisoner and were forcing him under torture to decoy the submarines.

“He requested by blinker the acknowledgment of his request,” he reported, “which I refused to give him until I was satisfied that it was actually Colonel Carlson. Consequently, I tried to send a message through to him on this order: The night before we had disembarked the raiders, at supper the Colonel and I had been talking over the fact that my father was a marine officer and had been head of the Adjutant Inspectors’ Department of the Marine Corps. In the course of the conversation we had discussed who had relieved him, and I knew that he would remember this and that if he gave me a prompt reply, I could accept as a fact that the Japs were not putting the screws on him, and that it was, in effect, he.

“So I tried to get this message through: ‘Who succeeded my father as A.N.l.?’ I got the ‘Who . . . ‘ out all right, but before I could go any further, I got a flash from the beach, ‘Please acknowledge, this is Evans.’

“So I again started all over, and again he interrupted. Finally he gave up and waited. And I got the test question through. I had hardly got the last letter au t before the flash came back from the beach, ‘Squeegy !’ That was the correct reply. The officer concerned was General ‘Squeegy’ Long of the Marine Corps. That was my way of identifying Colonel Carlson.”

Only four landing boats were still serviceable and these were carried from the sea beach to the lagoon, where natives provided an outrigger in addition. These five boats were lashed together and the 70 Marines still remaining paddled out to the waiting submarines.

By midnight all the surviving Marines were aboard and the two submarines headed back for Pearl Harbor, the scarlet flames of the fired Japanese aviation stores reflecting redly in their wakes.

The submarines returned, as they had come, independently, the Nautilus entering Pearl Harbor on August 25th, and the Argonaut a day later.

Each submarine on the return trip had seven wounded Marines on board. The operations by the surgeons were carried out under the most difficult circumstances, with relatively crude arrangements. But such was the skill of the two surgeons that not one of the casualties subsequently died.

“To me,” said the senior naval officer on the raid, “the most gratifying feature of this expedition was the spirit of cooperation between the raiders and the naval personnel. We trained the Marines to be lookouts, we gave them diving stations, and the crews of the submarines assisted in every way with the launching of the craft and the reassembly, reembarkation of the Marines upon their return. The crews and officers gave up their bunks to the wounded and to those Marines who were exhausted from their efforts ashore, and it is one of the greatest exhibitions I have seen of common self-sacrifice and helpfulness.”

The success of the Makin expedition resulted from this willing cooperation. “Unity of mind and effort,” as Lieutenant Colonel Carlson declared, welded the personnel of the submarines and raiders into an effective fighting team.

And it was eminently a successful expedition. It had caused a task force of Japanese cruisers, transports, and destroyers, en route to reinforce the Japanese on Guadalcanal, to change course for the Gilbert Islands. It gave us practical information about the enemy’s fighting equipment and experience in a new type of warfare. The submarine, though uncomfortable, proved it could be used for transporting troops for long distances.

A new technique had been tested. These two trail-blazing submarines were to playa continuing part in harassing the enemy as our forces crept closer, in the months to come, to Japan itself.