Airpower advocates exited the Gulf War trumpeting an unambiguous victory for airpower—and they were right. The air campaign against Iraq was well planned, brilliantly tailored to the adversary, and superbly executed. But it was also a clear example where the enemy was outclassed from the very beginning. Coalition forces were allowed an unfettered buildup, and had clear advantages in numbers, training, equipment and a doctrine designed to defeat massed Soviet and Soviet-client forces under adverse conditions. They faced a surrounded enemy who allowed the Coalition force to seize the initiative (despite ample warning) and keep it throughout the conflict. The Iraqi military at the time was postured to lose, and lose big.

At a distance of two years and after careful scrutiny of the evidence, some of the aspects of the war that seemed most dramatic at the time appear less so than they did in the immediate afterglow of one of the most one-sided campaigns in military history. Despite the talk of Iraq possessing the fourth largest army in the world, the fact remains that in this war a minor power found itself confronted by the full weight of the world’s sole superpower, amply and ably aided by the forces of its key allies.

— Gulf War Airpower Survey

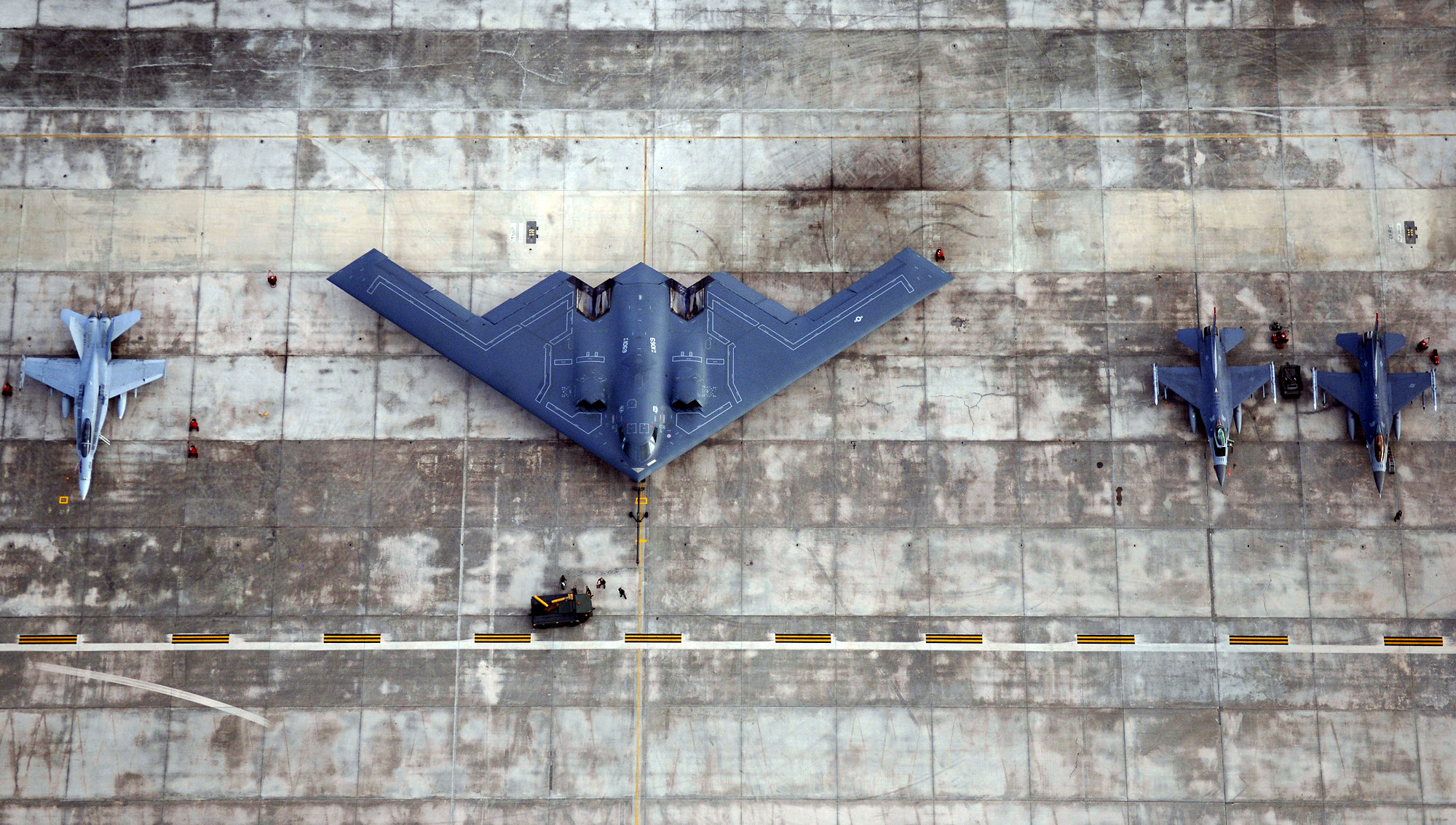

The U.S. Air Force came out of the war with what it believed was a winning template. Trumpeting the success of precision weapons, stealth and strategic attack, airpower practitioners misrepresented the means whereby victory was achieved. True, stealth allowed one aircraft type to penetrate air defenses, but a robust electronic combat triad allowed many more to succeed in the same environment. Precision weapons were employed well, but unguided weapons were used effectively, and made up the vast majority of the bombs dropped. Strategic attack against national-level leadership and communication targets was attempted, but of the 42,000 targets struck, fewer than 1,000 fell into that category and the Iraqi war machine was not decapited. Iraqi troops did leave Kuwait, but they left under pressure from fast-moving armored spearheads pressing from the west and south, not from 40 days of relentless air attack. An emerging school of airpower zealotry cherry-picked the results for the ingredients that they liked best, notably stealth, technology and the idea of a decapitation attack, and established a common template by which offensive airpower capabilities would be henceforth be measured. By settling on a subset of airpower drawn from a campaign against a woefully outmatched adversary, airmen did a great disservice to the design and employment of future operations, substituting a focus on servicing targets rather than executing strategies. As with investment portfolios, past performance does not predict future results. The nation’s potential enemies are sufficiently diverse as to require a flexible, adaptable airpower enterprise, and not a dogmatic adherence to a once-successful recipe. With warfighting strategies, one size fits none.

The Template

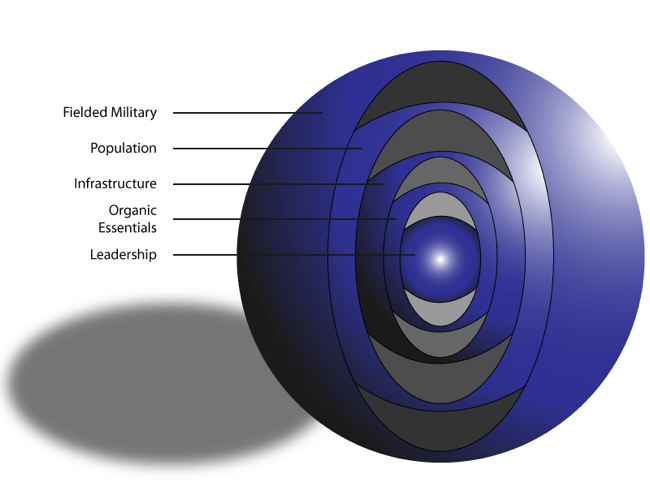

The air campaign against Iraq was classic AirLand Battle, the joint doctrinal construct intended to defeat a Soviet onslaught in Europe. While telecommunications and leadership targets were part of the target mix, it was hardly unique to Desert Storm. The final campaign plan brought together the capabilities that had driven Army and Air Force training, doctrine and procurement for about a decade. It worked exactly like it was expected to work, validating a great deal of post-Vietnam concept development. One of the concepts that the air campaign purported to validate was the “five ring” system model popularized by Col. John A. Warden III, whose initial draft of the air campaign consisted of only 84 “center ring” targets attacked in a week. In reality, this plan was rejected in favor of a much more comprehensive AirLand Battle campaign, but Warden’s theoretical construct got the credit.

The post-war template that eventually emerged drove the Air Force (but not the Navy) to shed a great deal of the critical airpower elements that had made victory not only possible, but quickly achievable at a relatively low cost. Precision munitions were in, as was stealth. Electronic warfare (EW), inexplicably, was out. The Air Force divested its EF-111 and F-4G fleet in the next five years, essentially abandoning any offensive EW capabilities not resident on the EC-130s. In its place was an automatic assumption that any air defense network could be effectively defeated in 72 hours, regardless of the actual correlation of forces. Interdiction was passé, while strategic attack—the mythical “decapitation attack” in particular—was the new airpower Holy Grail. Technology was in, often at the expense of both training and readiness. Col. Warden’s five rings were in, leading to more than two decades of a focus on targets that could be hit at the expense of a strategy framework that was focused on necessary actions to defeat an enemy rather than merely blowing up his stuff. And perhaps most important, it brought on an expectation of short wars where no such expectation was reasonable. Applying a previously victorious recipe was cheaper, faster and easier than doing the hard work of understanding an enemy, mapping his system, and building the kind of comprehensive approach required for an adversary who is not about to roll over in the face of air attack.

Allied Force should have highlighted the deficiencies of a short war mentality combined with a target-centric approach, but the urge to obscure the fact that NATO blundered its way to victory overrode a reconsideration of airpower application. Addressing the “short-war syndrome” in a widely disseminated after-action assessment, Adm. James Ellis acknowledged, “We called this one absolutely wrong” and asked if we would train for an air defense environment, “or continue to assume that we can take IADS down early?” But what should have happened and what did happen were widely divergent—the USAF doubled down with “Shock and Awe,” the strategy concept behind the air attacks in Iraqi Freedom. The 2003 air campaign was successful, but neither shocked the Iraqis into paralysis nor awed them into submission. The leftover Gulf War template, used against a weakened version of the same adversary, failed to live up to its prewar billing.

Global Power is the ability to hold at risk or strike any target anywhere in the world, assert national sovereignty, safeguard joint freedom of action, and achieve swift, decisive, precise effects. — Basic Doctrine (USAF), Volume I, Page 1

China: The Dragon in the Room

We are now a dozen years past the Iraqi Freedom air campaign, and many airpower professionals have still not shed the Gulf War template and their hope for a decisive center ring campaign. The ability to attack targets does not necessarily indicate an ability to successfully fight a war, much less win one. Furthermore, the effects of globalization have changed the very function of an industrialized state, and with it the exploitable vulnerabilities. A method that worked against an isolated, marginally modernized Baath Party dictatorship surrounded by hostile neighbors is no longer a good example to follow—if indeed it ever was.

The Air Force, and to a lesser extent Marine and naval aviation, retain a misguided focus on penetrating air defenses without a coherent strategy backing the requirement. There is certainly a place for the ability to penetrate air defenses, but it is a means and not an end. Discussions of a “salvo competition” are equally nonsensical—we cannot engage in a competition where we are dependent on island bases and prohibited from mere possession of an entire class of missile weapons while the People’s Republic of China faces no such constraints. And why would we?

China has spent a quarter century building a force designed to make absolutely certain that the United States cannot apply the Desert Storm template against the People’s Republic. The Department of Defense’s response has again been to double down on stealth and technology, as if the Chinese don’t understand either. Furthermore, the mere idea that we could execute either a shock and awe campaign or a decapitation strike against China is ludicrous on its face. China is a massive, technologically advanced country that has proven to be extremely resilient. During ten years of Cultural Revolution in which 1.5 million people were killed and leadership at all levels was systematically purged and re-purged, China mobilized for a near-war with the Soviet Union, endured a contracting economy, suffered factional violence, and muddled through with a shattered educational system. The state did not collapse and the Communist Party did not lose control of the military while it continued to develop a nuclear deterrent. There is no reasonable expectation of a short, victorious war against China unless the Chinese are the victors. If we’re going to fight China and emerge victorious, we’re going to have to do it the hard way.

China has a unique duality that the Warsaw Pact did not—we face real challenges in getting to Chinese shores and we cannot mass enough conventional power to have a decisive effect on purported center ring targets once we get there, assuming we knew what to attack and what effects we might expect. Any strategy against China must take into account unique vulnerabilities of the People’s Republic and plan accordingly. Even if China is not vulnerable to a rapid decapitation attack, it is surely vulnerable in other ways. As a nation that is almost entirely dependent on maritime transport to fuel its economy and provide energy supplies, China shares many of the same structural vulnerabilities as Imperial Japan. Starting more than a decade ago, the Chinese press extensively covered what it referred to as the “Malacca Dilemma”—the fact that almost all of their massive oil imports flow through a narrow waterway far outside their ability to project power. “It is no exaggeration to say that whoever controls the Strait of Malacca will also have a stranglehold on the energy route of China.” This might reasonably be a candidate for an interdiction strategy, which has a long record of success stretching back to World War II. Interdiction works because it is based in the reality that fighting a war involves a lot of matériel that mostly has to be moved by predictable surface transport methods. The impact of the loss of supply can be reasonably assessed, if not precisely predicted. The theory matches reality, has a long string of historical examples, and the effects are assessable.

Strategic architectures to deal with a modern China have emerged, but have yet to gain wide traction in the face of entrenched dogma. Col. T.X. Hammes, no airpower advocate himself, has outlined a formula for economic warfare at a distance titled Offshore Control. Strategic Interdiction is a refinement of offshore control that focuses on logistics rather than trade, targeting PRC energy infrastructure (especially jet fuel) to disable power projection. The Office of Net Assessment has researched a comprehensive strategy that starts with building capable Asian partners (hedgehogs) and incorporating a basket of nested operations to pursue multiple pathways to victory rather than just one. Dr. Andrew Krepinevich has examined the impact of “No Man’s Sea” (which is really more of an effect rather than a strategy) on modern warfighting in the Pacific. Every one of these studies takes into account specific characteristics of China, Pacific geography, and U.S. power projection capabilities as they actually exist.

Lesser Dragons

There are certainly lesser dragons. North Korea is an isolated, technologically backward mountain kingdom that has invested in intense fortification and a massive artillery and missile force. The DPRK military exists in a time capsule that relies heavily on mass and is no less dangerous because of it. Iran has unique naval techniques designed for the Persian Gulf, is effectively impossible to encircle and has demonstrated an amazing resilience to economic coercion. It has two and possibly three separate chains of command spread through a large country, backed by military forces used to operating on a shoestring. Syria maintains a fraction of its prewar offensive capability, but the government has managed to hold on to key territory and shows no signs of folding—with or without Russian combat power. Libya was so fragile that a relatively light application of airpower enabled disintegration of all of the state’s control measures. All of these countries require a strategic approach tailored to their unique character rather than a formulaic approach that is tuned only around the edges.

An entire clutch of lesser dragons has proven completely resistant to an unambiguously target-centric approach aimed at leadership. Tactically brilliant, efforts by SOCOM and the CIA to find and eliminate terrorist and jihadist leaders have been occasionally successful for more than a decade. However, there is no evidence to suggest that it has had a positive strategic effect and every reason to believe that the effort has made the Jihadist insurgencies more robust, more resilient and more dangerous. The evolution of Bayat al Imam from a Jordanian terrorist group to Jama’at al-Tawhid w’al-Jihad to al Qaeda in Iraq to a precursor of the Islamic State occurred despite severe damage to its leadership, including the killing of its co-founder Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. The loss of Zarqawi and the departure of his foreign fighters gave al Qaeda an impetus to become a more local organization and it picked up new leadership that was less fratricidal, more disciplined and ultimately more effective. Those leaders now run the Islamic State, a far more dangerous actor that al Qaeda ever was. We could not accurately predict the operational or strategic effects of our attacks on leadership and may have inadvertently accelerated the development of Jihadist networks into more capable, virulent and dispersed adversaries.

The Impact on National Strategy Development

Strategy development is difficult, and it made more difficult by disdain in the DOD for the need to develop it. The Air Force has no career path to develop airpower strategists, no educational pathway to create them, and no program to refine their skills. It is trapped in an echo chamber of its own making, where it devotes considerable time arguing with itself and other services on whether airpower is or can be decisive rather than examining the cases where it was effective and understanding why it was so. Airpower advocates cannot give good advice or provide effective guidance if they do not understand the “why” behind the “what” and apply it to the “who” and the “where.”

The DoD has long exacerbated the problem. The focus on “capabilities based planning” openly disregarded the need for considering actual adversaries in favor of matching their systems with ours. This means that even at the department level we have shunned the ability to develop strategy in favor of developing capability portfolios. Making a bad problem worse, the isolation of procurement decisions from the context in which systems might be employed raises the likelihood that a program will deliver materiel that is poorly suited for its intended warfighting role. If we do not have the ability to match equipment, training, concepts and expected outcomes to a potential adversary’s vulnerabilities, we do not have a warfighting strategy.

These institutional failures have effects at the national level. Execution of an effective national security strategy is not merely the purview of the DOD but it requires close cooperation with other departments, including the Department of State. It also requires broad guidance that has been lacking even at the national level. Despite an annual requirement enshrined in the Goldwater-Nichols Act, there were no revisions of the National Security Strategy from 2010 to 2015 and no new National Military Strategy from 2011 to 2015. Those are broad-level documents what should have been shaped by detailed strategic advice that the services were not developing. This is not entirely the fault of policymakers, whose expertise lies elsewhere, but providing credible strategic advice is the responsibility of the services. The 2015 National Security Strategy is not so much a strategy as a political manifesto that highlights past achievements more than it outlines an executable strategy. That lack is echoed by the 2015 National Military Strategy, which at least offers a description of the challenges in the context of the geopolitical environment. As national-level documents, they need not provide details that would be required by a war plan, but neither can they be an exercise in self-deception about what we can or should accomplish. Strategies are not effective if they are not matched to appropriate resources. The so-called “Pivot to the Pacific” is a prime example—it is a nebulously vague catchphrase that is yet unmatched by a significant fraction of the resources needed to execute.

Knowing the “Why” of Airpower

The development of airpower strategy is a fundamental responsibility of airmen, and it is the reason why we have an independent Air Force. A target list is not a strategy and wishful thinking about airpower theories that offer a quick route to victory should remain the purview of storytellers and movie directors—not military professionals. Quick routes to victory are limited to battles where the adversary is outmatched, the stakes are small, or other conditions prevail which combine to place one side in an untenable position. We cannot afford to persist in the belief that that airpower employment can be employed by a “one size fits all” formula.

As strategies drive resource demands, resources establish the limits of achievable strategies. Airmen need to invest the capital to make sure that these interdependencies remain synchronized, tailorable, and achievable. That capital takes the form of training, education and readiness as well as technology and materiel, and we cannot focus on one aspect (like hardware) and expect the others to somehow follow. The effort to maintain a credible, effective airpower enterprise that provides National Command Authority with achievable strategy options is not a small one, and is not helped by formulaic responses, an overriding faith in technology, or underinvestment in trained, educated and experienced Airmen. Knowing and articulating the “why” of airpower is a basic responsibility and the keystone that supports the bridge between ways and means and the all-important ends. Targets only matter in the context of a strategy goal and are only one component of strategies that matter.