In the U.S. Navy’s perfect world, the service will reach its goal of a 306-ship fleet by 2020, according to the service’s latest 30-year long-range shipbuilding report, submitted to Congress on July 1 and obtained by USNI News on Monday.

But the likelihood of the service ever reaching that goal is still an open question — one made no clearer by the new report, which is loaded with caveats and assumptions.

The congressionally mandated 30-year shipbuilding plan is arguably one of the most criticized documents from the Pentagon.

For example, Rep. Randy Forbes (R-Va.) delivered his annual assessment in a Monday statement to USNI News.

“The new shipbuilding plan lacks the resources to be anything more than a piece of paper,” said Forbes, chairman of the House Armed Services Subcommittee on Seapower and Projection Forces.

“With a continued . . . shortfall in the shipbuilding budget, even the Navy’s minimalist goals will remain unfulfilled absent a reversal of sequestration or a decision to prioritize Navy investments over other national security goals.”

In this most recent edition of the report, the Navy points to more-than-usual stumbling blocks in the way of getting the money and resources it needs to build and maintain the 306-ship fleet.

The list includes overcoming ongoing sequestration cuts, an assumption that the service’s ships meet their expected service lives and finding additional funding for Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Jonathan Greenert’s number one priority — the $100 billion Ohio Replacement nuclear ballistic missile submarine program (ORP).

Sequestration

For starters, the law and the Navy disagree how much money the service has to spend on ships.

The Navy’s budget submission earlier this year for ships in the five-year period of the Future Years Defense Plan (FYDP) does not account for the Budget Control Act of 2011 mandated sequestration cuts in its shipbuilding accounts.

The Navy’s FYDP assumes an average $14.7 billion shipbuilding budget (SCN) per year. The difference between that top line and the realities of sequestration are about the cost of a guided-missile destroyer

With sequestration, the shipbuilding accounts is 12 percent —or about $1.76 billion — lower per year, according to estimates from an April Pentagon report on how sequestration would affect the military’s bottom line.

And the likelihood of the service making up the gap in funding is slim.

Congress’ repeated reticence to remove the spending limits within the 2011 Budget Control Act (BCA) is unlikely to change anytime soon, several legislative sources continue to tell USNI News.

The Navy’s assessment is also shackled to the larger Pentagon political fiscal strategy of submitting budgets that ignore sequestration cuts while making persistent requests for Congress to eliminate the funding shortfalls.

For example, Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel delivered an ultimatum to Congress that without the removal of sequestration cuts, the Pentagon would decommission the aircraft carrier USS George Washington (CVN-73) and eliminate the carrier’s air wing.

However funding to keep the ship in the fleet has been a staple of several versions of current set of defense funding bills with no sign of the sequestration cuts being removed.

It’s unclear how sequestration cuts would affect the shipbuilding accounts long term. The April sequestration report from the Pentagon said the Navy would lose eight ships across the FYDP and could lay up as many as six destroyers, but provided few other details past 2019.

A $100 Billion In Submarines

If the BCA restrictions weren’t enough, the Navy identified “significant challenges to resourcing the [Department of the Navy’s] shipbuilding program,” outside of the sequestration limits.

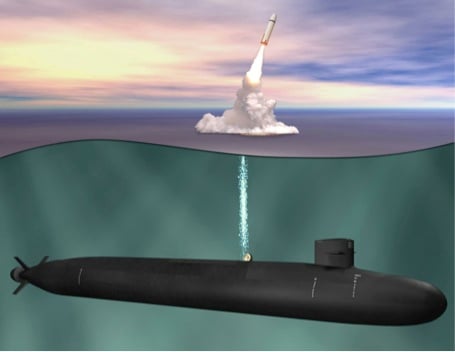

Beginning in 2021, the Navy will begin buying its replacement for the 14 Ohio-class nuclear ballistic missile submarines (SSBN) — the Navy’s share of the U.S. strategic nuclear deterrent.

From 2021 to 2035, the service’s estimated shipbuilding budget will rise to about $24 billion a year at the peak of the SSBN program — double the Navy’s $13 billion historic shipbuilding budget.

The service has said in the past it would need an injection of $60 billion over 15 years in the shipbuilding account to prevent a reduction in the number of other ships it buys,

“Just using some generic examples: If we only get half of that [$60 billion], we will lose 16 ships out of the Navy’s inventory that we would otherwise procure in that time. . . . With only half of that assistance [$30 billion], you’d lose four [attack submarines], four large surface combatants and eight other combatants,” Rear Adm. Richard Breckenridge, the then Navy’s director of undersea warfare, told the Seapower subcommittee in September.

“If we get zero, you’re looking at 32 less ships.”

Says the latest version of the 30-year report: “The [Navy] can only afford the SSBN procurement costs with significant increases in our topline or by having the SSBN funded from sources that do not result in any reduction to the [Navy’s] current resourcing level.”

Expected Service Surface Life

One of the key assumptions of the Navy’s plan is that it will retain existing ships to the end of their expected service lives (ESL), which range from 30 to 50 years, depending on the ship class.

It’s almost a foregone conclusion the Navy will keep intact the exhaustively planned schedules of its nuclear carriers (50 years) and submarine fleets (33 to 50 years) but the ESLs of the service’s non-nuclear surface fleet have a been a moving target, depending on whom you ask.

The service’s requirement for large surface combatants — a stable mix of 88 guided missile cruisers and destroyers — has remained constant from the last year’s shipbuilding plan to the current version.

The assumption that the large combatants will reach a 40-year service life is integral to the underpinnings of the Navy’s 30-year plan.

The Navy sees small dip below 88 in 2034, but its curve holds mostly at or above the target.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO), however, in its assessment of last year’s plan, asserted that the Navy’s ESL math for large surface ships was incorrect.

“The [Navy’s] plan would fail to meet the goal of 88 large surface combatants (destroyers and cruisers) in 2030 and beyond,” according to the CBO.

“The Navy assumes in its plan that most of its destroyers will serve for 40 years, even though the Navy’s large surface combatants have typically served for 30 years or less. If the current destroyers serve for only 35 or 30 years, the shortfall in large surface combatants would be more than twice as large as projected in the Navy’s plan.”

According to CBO estimates, a 30-year service life would mean a cruiser and destroyer drop to below 88 as early as 2017.

Maintenance

The CBO’s estimated ESL shortfall could come faster depending how well the Navy is able to maintain its current cruisers and destroyers.

For much of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, the Navy’s surface ships had inconsistent maintenance that was deferred because of operational needs.

In 2009 the Navy began an extensive program — led by Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA) — to make up for years of poor maintenance.

However, sequestration has threatened to derail the five-year old program with funding lapses, which could lead to skipped maintenance availabilities and — in turn — a service life shorter than even the CBO estimates.

“You can’t build your way to a 300-plus-ship Navy,” then-Naval Sea Systems commander Vice Adm. Kevin McCoy told Proceedings shortly before his retirement in 2012. “We needed the 300-plus ships based on our analysis of the world to do our mission.”

According to the April report, the Navy could see a reduction of up to 30 percent of its depot level maintenance availabilities under sequestration.

Questions About LCS Unanswered

One question left unanswered in the 30-year plan is how many small ships the Navy can afford to field. Right now, the Navy wants 52.

But the Littoral Combat Ship program — the Navy’s plan to replace several classes of ships — underwent a major shakeup in February following a Hagel-directed study to revaluate both the Freedom and Independence LCS classes.

Hagel asked the Navy to find a tougher and more lethal ship.

The ongoing Department of the Navy study has a mere five months to evaluate variations on the existing hulls and new designs before it’s the end-of-July deadline.

How the results of the plan will affect the bottom line requirement for the Navy’s smaller ships is yet another open question. Making a ship tougher and more lethal comes with a higher price tag.

As a result, the Navy could easily reduce the numbers to make up for any increased cost of the ships as part of the LCS restructure.